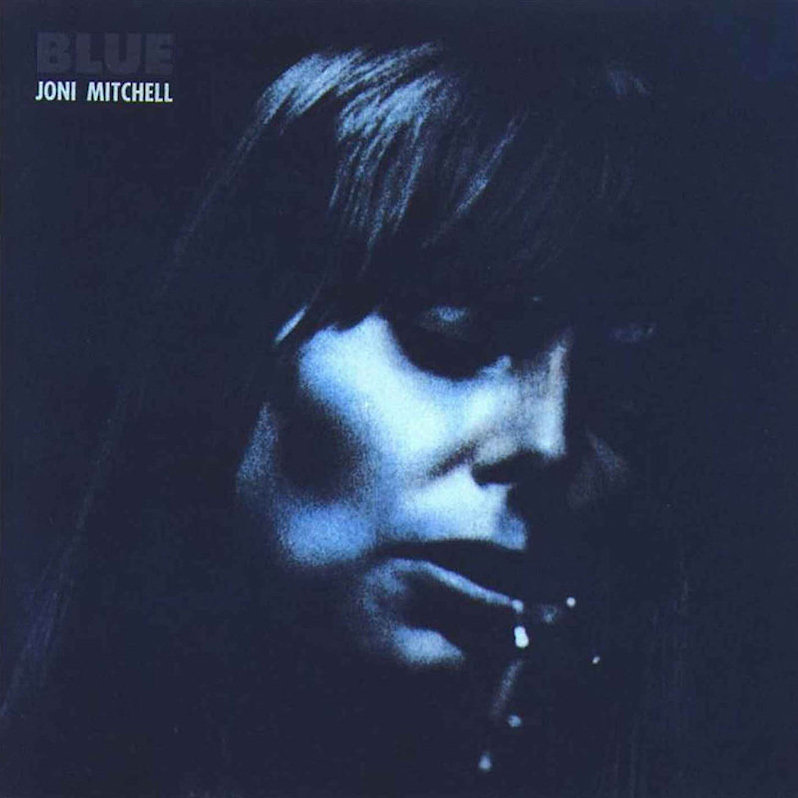

During the summer I experienced the grueling transitioning from middle school to high school, my mother introduced me to the music of Joni Mitchell. The first album she picked had a navy-colored cover with a long-haired woman’s face on it: Blue. I wasn’t sold immediately. Maybe I wasn’t mature enough to sink into the sadness, to interrupt the sorrow of her beautiful contemplation of life as a rising star. I got into her jazzy Court and Spark, her upbeat musings on love and on loving her freedom. Yet as I came back to Blue both in college and out of college, I have come to appreciate her pain and her blues. And in turn, her blues helped keep away my own. Hearing someone else’s easy-to-relate-to experience of loss and regret and grief made me feel a connection—it made me feel just a little less lonely.

A lot has been written on Blue. It is Joni Mitchell’s most highly acclaimed album—the third greatest album of all time in Rolling Stone’s list of the “500 Greatest Albums of All Time,” as well as one of Treble’s own top 10 favorite albums of the ’70s. The album’s main inspiration was Mitchell’s travels in Europe, being away from home and away from the spotlight. It’s also deeply personal and open in a way that even her prior albums hadn’t been. The second track, “A Little Green” is an elegiac remembrance of the daughter that she had to give up (“she’s lost to you”) because she didn’t have a husband (“he went to California”) or a career yet. The song’s style and mood is reminiscent of her previous album, Ladies of the Canyon (1971), and it is a tender reflection on her child, her firstborn that she couldn’t keep, because she “was a child with a child.” Mitchell’s lyricism stands apart from that of any of her contemporaries of the early 1970s in its poetic nuances and clever wordplay. She is a master of relaying her emotions, her ideas, her everything to a listener. As she says herself, “You don’t have to dig under the words.”

Lines such as “I hate you some/ I love you some/ when I forget about me,” from the album’s leadoff track “All I Want,” speak volumes about who Joni Mitchell is. Exploring relationship dynamics is nothing too new, especially for Mitchell—think back to “That Song About the Midway,” “Conversation,” as well as songs she’d release on later albums. It’s become a lyrical staple for her, an idea that she reflects on often in her career. With her classic guitar playing, “All I Want,” is both one of the album’s best albums and one of the strongest in her career as a whole. It pairs with her fourth song “Carey” well, too, both featuring a similar tone and guitar sound—more animated and with more tooth, more energy to them, which is a little less prominent as Blue continues on (which is by no means a problem or a criticism).

Blue isn’t necessarily flawless in a literal sense, but even the less dynamic moments speak to something vulnerable and real. In fact, the title track, “Blue” is one of the more understated moments on this wonderfully raw record. It reminds me of her earlier music actually—slightly unsure of where to go. Perhaps this parallels her physical situation of not knowing where to travel to next, or her just-ending relationship with James Taylor. Her voice, which can be so quiet and susurrous at times, is warbly and, as my mother says kindly, occasionally screechy. Mitchell—having used many of her paintings as album covers—no doubt brings in some color symbolism here and there. “Blue,” with its elegant piano playing, is a strong song that leaves its impact in large part through what isn’t there; it gets Mitchell’s point of feeling isolated across (“River” also does this with great results), but it doesn’t soar above the sorrow. Yet, as she puts it herself, “sometimes there will be sorrow.”

After the success of Blue, Joni Mitchell delved deeper into jazz. Court and Spark and Mingus show a move away from folk melodies. However, their themes of love and everyday things like coin rolls or summer lawns or cars on hills or a brood mare’s tail can be traced back to her earlier projects. Her concerns with relationship dynamics or being a prisoner of the “free freeway” appear in Blue. In “A Case of You” she considers the idea of being constant as a northern star and makes a quip about being constantly in darkness. Tasting “so bitter and so sweet,” Mitchell is “still on [her] feet” even after heartbreak, disillusionment. In Mitchell’s music everything is about being connected, about how things join together and fall away. Her melodies come and fade and come again. Her style of playing and her way of layering her tunes with harmonies sung by herself is classic; it’s uniquely her own. Though she changes and shifts her musical aspirations, Mitchell is constant as a northern star in the way she employs music and verse to relay genuine emotion.

Joni Mitchell is special to me; she is my favorite singer and songwriter of all time. I share this love for her music not only with my mother but also with my piano teacher—who occasionally sings snatches from “A Case of You.” She even keeps flowers around her grand piano (a little hat tip to “Carey”). Two of the most special people in my life have been touched by Mitchell’s music and words, and in turn I have as well. So much in music has changed, evolved, returned to, and been reworked in the 50 years since Blue was first released. But Joni Mitchell is still Joni Mitchell. Even with her last release Shine in 2007, it’s easy to recognize the genius that sang so mellifluously, that wrote so openly in tracks like “This Flight Tonight.”

After passing the 50-year mark, Blue might not have the same dynamic punch, the newsworthy drama of a recent breakup, but it still contains all the emotions and ideas that accompany a relationship in its final throes. Listeners can still learn something about life, about healing and living with grief without it taking over—which can feel especially poignant following a year like the one we just experienced. Blue is atmospheric at times, melody-forward at others, and her guitar and piano playing is top drawer, refined and thoughtful. Nothing is left to chance, even in her jazzier moments. Mitchell is a true pioneer, pushing boundaries and returning to old structures—like the faux “Jingle Bells” bit at the beginning of “River”—and Blue is a monument in her career. It is by no means an end, but it marks a peak, a high point where her talent mixed with raw emotion to create something special, something indelible.

***

This article was originally published in 2021 and has been updated.

Note: When you buy something through our affiliate links, Treble receives a commission. All albums we cover are chosen by our editors and contributors.

Support our Site—Subscribe to Our Patreon: Become one of our monthly patrons and help support an independent media resource while gaining access to exclusive content, shirts, playlists, mixtapes and more.

Hi,

What happened to No. 26?

#26. is Funkadelic’s ‘Maggot Brain’ and it’s on our Patreon. We’ve posted about seven or eight there throughout the series.