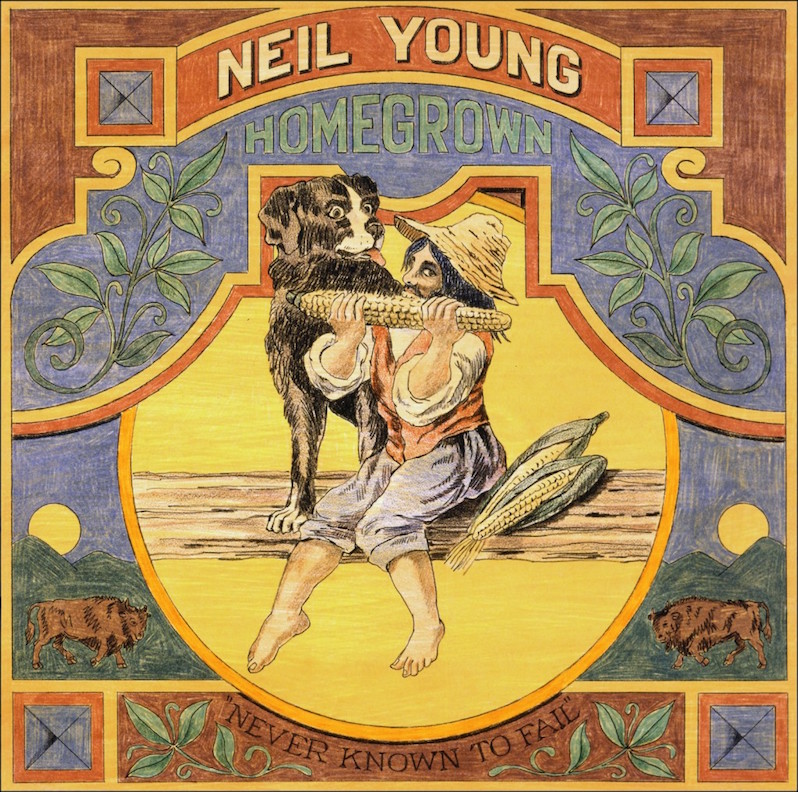

Neil Young : Homegrown

Albums get lost for all sorts of reasons. Their creators have nervous breakdowns or bad ecstasy trips. The master tapes get snatched, or they get snatched back. They get abandoned when the concepts become “too whimsical” or too damn complicated. Personal conflicts with your bandmates can derail the recording process—so can politics. A lot of times, the label just says no. Sometimes, they literally do get lost.

Still, the tale of Homegrown, and Neil Young’s decision to withhold it, is widely regarded as one of the most baffling in rock history. For those unfamiliar with the story: Young was in shambles in 1974, reeling from the drug-related deaths of guitarist Danny Whitten and roadie Bruce Berry, the debaucheries of the “Doom Tour” with Crosby, Stills & Nash, and the collapse of his relationship with actress Carrie Snodgress, with whom he had a son. Their estrangement (and eventual breakup) in particular cast a shadow over many of the 30 songs that Young recorded in the second half of that year, and by January 1975 he had assembled a dozen of them into an album he named Homegrown. Preparations were made for its release: A cover was created, and Young played a tape of the record at a listening party for friends. But the tape kept playing after Homegrown finished, and it just so happened that the reel also contained Tonight’s the Night—another yet-unreleased album, largely recorded in August 1973 in a blur of long nights full of substance abuse, when the memory of Whitten and Berry’s deaths was still uncomfortably fresh. After revisiting the older, rawer material, Young impulsively dropped Homegrown and went ahead with Tonight’s the Night in its place.

Though it was far from the last time that he would confound the expectations of his listeners and his label, Young’s explanations for shelving Homegrown have never made much sense. For years, the pull quote about Homegrown was that it was “just a very down album”—and that makes sense from a purely musical standpoint, as the majority of its tracks are acoustic and unhurried. But while Tonight’s the Night doesn’t sound like a downer, it never fails to remind you that, at its core, it is an album about death and destruction—look no further than the title track. This also contradicts Young’s other claim about Homegrown: that it was simply too personal, too painful, to share with the world. The end of a relationship is deeply personal territory, no doubt, but…so is the death of two close friends (let alone feeling responsible for one of them). Where Tonight’s the Night sounds like an open wound, listening to Homegrown feels like pressing a hand on a bruise.

Nevertheless, nearly 46 years after it was laid to tape, Homegrown can finally be heard as it was meant to be heard. (Unlike several other lost albums from Young, bootleggers never reached a consensus on Homegrown’s track listing, which wasn’t even publicly known until the record was officially announced.) Seven of its 12 tracks were unreleased until now, and an eighth assumes its original acoustic form. The familiar moments offer a few tricks, but mostly treats: The title track, described as “a goofy tribute to hemp,” was first released on American Stars ‘n’ Bars in 1977, and the slightly different take on Homegrown serves as a mid-album pick-me-up. Also from American Stars ‘n’ Bars is “Star of Bethlehem”—coming right after Hawks & Doves’ delicate “Little Wing” (both songs appear unchanged), it makes for an affecting closer to the LP.

It’s “White Line” that undergoes the greatest transformation, shedding the distorted electric guitars that adorned it on 1990’s Ragged Glory. Homegrown’s “White Line” is markedly different—tender, even vulnerable—yet it complements the later version like the other side of a coin. But even in its new (old) form, it casts no more light on the titular metaphor, whether the “white line” Young sings of in the final stanza is a drug reference or something more abstract. Heard in this way, “White Line” doesn’t sound like a demo, but rather the definitive version of the song.

As for the previously-unheard tunes, it’s quite possible that had Homegrown come out in 1975, several of them would have ranked among the best that Young ever wrote. The first two songs, “Separate Ways” and “Try”, can hold their own against Young’s very best, and they open the album like a gut punch—“Separate Ways” finds Young resigned to the end of he and his ex-partner’s relationship, trying to tell himself it’s for the best, singing, “me for me, you for you / Happiness is never through / It’s only a change of ways.” But by the next track he’s already trying to find her address, convinced it’s not over: You can read the refrain, “we got lots of time / To get together if we try,” as either a genuine plea to work things out or the hollow words of someone who just can’t let it go. He wakes up beside a new woman on “Kansas,” the heart of the record, but there’s something fragile and tentative about this new love—if it can even be called that yet. “It’s so good to have you sleepin’ by my side,” Young coos, as if not to wake who he’s singing about, “although I’m not so sure / If I even know your name.”

It’s in Homegrown’s middle stretch, when Young strays from the themes of heartbreak and melancholy, that the album’s spell breaks somewhat. The title track is purportedly about the joys of growing your own marijuana, which gels with what we know about Young but not so much the content of the album; ditto for “We Don’t Smoke It No More,” a dopey, bluesy jam whose lyrics can’t help but feel like a not-especially-funny joke. (The unsung punchline: Yeah, but we still do it!) The only out-and-out dud is “Florida,” a bizarre spoken-word piece about a hang-gliding accident, where the only instrumentation is provided by wine glasses and piano strings. Perhaps Young, in an inebriated state, thought this contributed something to the record, but to the rest of us, “Florida” is wasted space that could (and should) have gone to an actual song, like “Love / Art Blues” or “Homefires”—both of which remain somewhere in the vault.

Still, it’s hard to get too sore about the performances on Homegrown. The title track and “We Don’t Smoke It No More” are lightweight, yes, but it’s fun to hear Young get silly like this. (Homegrown’s other rocker, the Crazy Horse-esque “Vacancy”, is a real treasure.) Frequent Young collaborator Ben Keith contributes lap slide guitar to these songs, and his pedal steel guitar on “Separate Ways” and “Try” is simply gorgeous, almost as if its strings are welling tears. Emmylou Harris’ voice—a similarly plaintive and expressive instrument—makes for a welcome addition to “Try” and “Star of Bethlehem,” and Young’s own singing all over the album is as expressive as it’s ever been, gentle and unforced and hushed. He’s long used roughness, even sloppiness, in his music to convey feeling, but Homegrown features some of the most intimate and straight-up beautiful material of Young’s career.

And now that we can finally hear Homegrown for ourselves, we can assess exactly how it fits into Young’s career. In the Jimmy McDonough-penned biography Shakey, Young called Homegrown “the missing link between Harvest, Comes a Time, Old Ways and Harvest Moon.” But the best lost albums do more than just neatly fill an empty space, and Homegrown—to a much greater extent than the previously-released Hitchhiker—raises questions even as it answers them. Had Homegrown come out in 1975, what would the critical and commercial response have been, and where would it rank among his discography today? Would Tonight’s the Night still have been released, or would it have taken Homegrown’s place as the most storied of Young’s lost albums? These questions and the alternate scenarios they raise feel irreconcilable, and without the knowledge of what Homegrown might have been, we’re left to consider what it is—the end of the romance that Young began on Harvest, and the long-unpublished fourth installment in the fabled “Ditch Trilogy.” Above all, Homegrown is a reminder that what once was lost, be it love or music, may once again be found, just not when or where we expect.

Label: Reprise

Year: 2020

Similar Albums:

Neil Young – Storytone

Neil Young – Storytone

Willie Nelson – First Rose of Spring

Willie Nelson – First Rose of Spring

Bob Dylan – Blood on the Tracks

Bob Dylan – Blood on the Tracks

Jacob Nierenberg is a man of contrasts: a Pacific Northwesterner who carries an umbrella, a pacifist who enjoys the John Wick movies, an idealist who follows politics. Scarcely a day goes by that he doesn't talk with his best friend (and fellow Treble contributor) Tyler Dunston, the Jim Morrison to his Bernie Sanders.