Pick Your Poison: Junior Kimbrough vs. R.L. Burnside

Legend has it that, in 1992, in the rolling hills of Chulahoma, Mississippi, at a little juke joint called Junior’s Place—founded by the late, great Junior Kimbrough himself—you might find Bono, or Iggy Pop, or Keith Richards, or Kim Gordon, nestled into a scattered crowd of Chulahoma natives, drunk on corn whiskey and listening to—no, feeling—an undeniably subversive and enchanting type of sound: the Hill country blues.

This esoteric sub-genre of a typically predictable and awfully stereotypical school of American music brought demons to life, revitalized the spirits buried six feet beneath the listener, set the world to a series of pulsating frequencies and vibrations. The Hill country blues was made famous by—at least within a specific and intimate crowd of indie listeners and crate-diggers—Junior Kimbrough, R.L. Burnside, “Mississippi” Fred McDowell, Robert Belfour, and Calvin Jackson. The Hill country blues is perhaps the steadiest style of blues you might hear—sporting prolonged, droning rhythms, there is space in this very rare, uniquely obscure blend of blues and pure, unalloyed melancholia. Its few forefathers expanded upon a sound that was, routinely, overwhelmingly simplistic—though overtly emotional and honest—and its distinctive qualities focus less on the literal music and lyrical content as it does on its hypnotic semblance, its mesmerizing DNA make up of broken hearts and unbounded isolation.

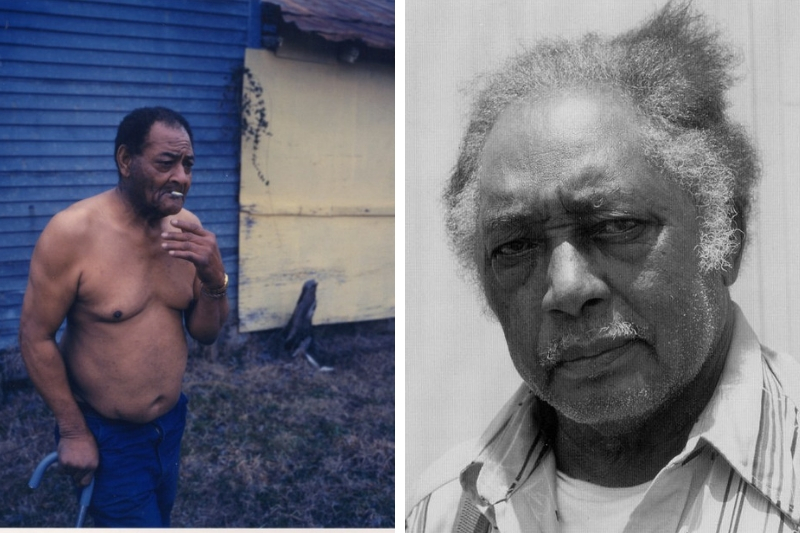

But perhaps the two artists that embodied and best articulated the specificity of the Hill country blues were Junior Kimbrough and R.L. Burnside, two northern Mississippi-born blues artists who were local legends and “rediscovered” by the Oxford, Mississippi label Fat Possum Records, who originally established themselves as a sort of archivist label, releasing and re-releasing arcane blues artists from the northern Mississippi region, where Kimbrough and Burnside both hailed from, respectively.

Kimbrough and Burnside were placed into similar realms by music journalists, archivists, labels, and listeners, and for good reason—they were acquaintances, they released music through the same label, they both shared a great deal of critical acclaim, and, as mentioned previously, they were both obscured blues-gurus hidden in the hills of northern Mississippi. There’s a certain mystique shared between the two, and furthermore embraced by the media and fans of their music (typically fanatics).

Though these two artists share numerous similarities and common attributes, however, both styles are derivative in their distinctiveness: Burnside, when accompanied by other musicians, or a full band, is more rambunctious, jovial, playful. His solo recordings are indeed more sparse and emotive, but within his extensive discography these are seldom. Kimbrough, on the other hand, is blatantly depressive, squealing and crying and cooing alongside his masterful guitar work, which tinkers with traditional major and minor blues scales and flips them upside down, smashes them into the dirt, doing things on his guitar’s fretboard that you’d swear only the devil was capable of. Burnside, too, was capable of this, but his work sounds more raggedy, bouncing around as he shouts and yelps and cries out to his band, which usually carries a sort of bump and grind rhythm—especially on his 1981 debut, Sound Machine Groove.

Kimbrough’s discography is much more scarce, summing up to a reissued First Recordings, originally released in 1966, then re-released in 2009 by Fat Possum, followed by All Night Long (1992), Sad Days, Lonely Nights (1993), Do the Rump! (1997), Most Things Haven’t Worked Out (1997), God Knows I Tried (1998), and Meet Me in the City (1999). The bulk of these songs derived from some of Kimbrough’s “standards,” such as “Meet Me in the City” and “Done Got Old,” featured on First Recordings, and others such as “All Night Long,” “You Better Run,” “Sad Days, Lonely Nights,” and “Keep Your Hands Off of Her.” The bulk of these songs were covered by the Black Keys on their 2006 tribute album, Chulahoma: The Songs of Junior Kimbrough, which graciously captured the energy found on Kimbrough’s originals.

If you were to first listen to First Recordings, you may find the rambunctious nature of the songs similar to that of R.L. Burnside’s discography, but the older Kimbrough grew, the moodier his music became. Burnside’s discography followed the opposite track—throughout 13 studio albums, six compilations, and two live albums, Burnside grew more playful in his nature, a slap-happy aura flowing throughout the bulk of his music. Kimbrough wasn’t the only one of the two who worked with or were praised by indie stars, though—Burnside’s 1997 album A Ass Pocket of Whiskey was produced by and featured Jon Spencer’s Blues Explosion, while other albums of his—1998’s Come On In and 2004’s A Bothered Mind—were remixed by, unfortunately, artists such as Kid Rock (A Bothered Mind), but fortunately remixed by artists such as Tim Rothrock, who made his name mixing and producing for Beck. Some of these songs found throughout Come On In were transformed into bizarre, trip-hop renditions, while others remained in their spare and heartfelt nature.

The impact of these two artists are not dissimilar, as both have been praised as masters and innovators of not only the Hill country blues, but the blues at large. Burnside enjoyed a lengthier tenure, as Kimbrough passed away of a heart attack in 1998, at the age of 67. Burnside outlived Kimbrough by seven years, passing away from poor heart-health in 2005—surviving a decade longer than Kimbrough—at the age of 78. Their legacies will forever be tied together, neatly in the hills of northern Mississippi, their spirits delighting and inspiring the rawest and most sincere blues music imaginable. But when they are held up together, side-by-side, Kimbrough’s awe-inspiring recollections of love-stricken madness remind one of a Shakespearean tragedy, its depth and influence boundless, while Burnside’s overwhelming and infinitely excellent blend of jumpy and exciting blues-rock gets squashed by the relentless passion of Kimbrough’s mastery. May the two rest in peace, and may their souls forever haunt the listeners of their music, fueled by an innate sense of empathy and feeling for mankind—but when it comes down to it, Kimbrough takes the title as one of the finest blues-guitarist and songwriters of the last 100 years.