Nothing can cause an existential crisis quite like a hit song. Some artists will spend half their lives trying to chase a hit, only to turn around and spend the next half just trying to get as far away from it as possible. It’s as much a blessing as a curse, a flood of fame and fortune like that always comes with too many strings attached—one of them being the incessant repetition of a melody you’re eventually going to tire of hearing. It’s a rare artist that can keep a string of hits going—Rihanna, Taylor Swift, Janet Jackson—but following up the first one is the hardest. It’s enough to drive someone off the deep end.

Scott Walker, née Noel Scott Engel, spent the better part of his career plagued by a hit. As a member of The Walker Brothers, a UK-based singing group whose American-born members weren’t related and didn’t actually bear the surname Walker, he landed a massive hit with “The Sun Ain’t Gonna Shine Anymore” in 1966. The song climbed the charts in nine countries, reaching number 13 in the U.S. and number one in the UK, becoming their signature song (though they weren’t the first to record it). An orchestral pop song big on drama and melody alike, it’s a celebrated standard, and one that made them—if ever so briefly—bigger than The Beatles in the lads’ home country.

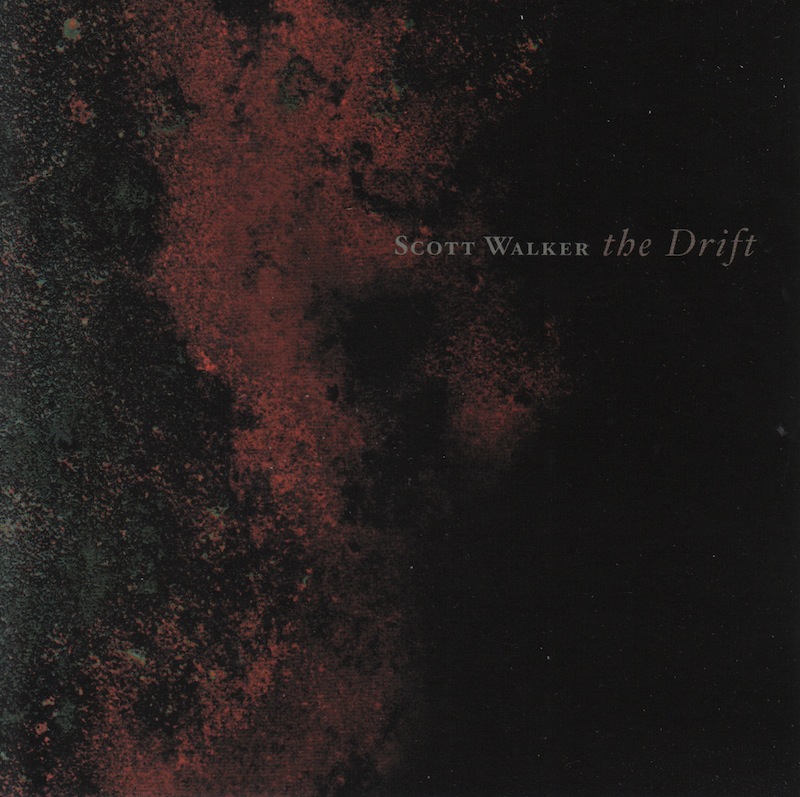

The image of Scott Walker the debonair hitmaker, spawning a massive fanclub of screaming devotees, is one that’s hard to square with the architect of nightmares on 2006’s The Drift. Abrasive, difficult, and perpetually bristling with prickles of terror, The Drift isn’t a pop album by any ordinary metric. A gothic operetta invoking the horrors of 9/11 and the grisly final days of dictators—a particular fascination for the singer/songwriter—it scarcely allows a major chord to slip through during its 68 minutes. It’s at once a cry from the edge of the abyss and a punchline from the gallows.

“The Sun Ain’t Gonna Shine Anymore” might have been an early warning of the dark path he’d eventually take, its verses draped with images such as “loneliness is a cloak that you wear.” A tuneful song, for sure, but no day at the beach. And though that wasn’t one of Walker’s original compositions, the ballads he wrote for the group’s 1967 album Images failed to live up to the promise of “The Sun,” and Walker Brothers mania dissipated nearly as quickly as it rose. Scott quit the group to learn Gregorian chant at a monastery, fell in love with the music of Belgian crooner Jacques Brel and released a sequence of ornate, haunting solo albums all titled Scott (the second, third and fourth in the series marked by sequential number), that saw him consumed with the films of Ingmar Bergman and images of destruction wrought by giant fists from the sky. When those albums all proved just as commercially unviable, he shed his avant garde sensibility for several dollar-bin albums of standards, movie and cowboy songs that were somehow even more commercially disappointing—and which he could barely stand to acknowledge even years after the fact.

Walker designs a labyrinth of psychological horrors and jump scares alike, his elaborate and shrieking compositions owing more to the avant garde composition of Krzyzstof Penderecki and Gyorgi Lygeti than actual rock music.

“Well, I was trying to hang on,” he told The Guardian. “I should have stopped. I should have said, ‘OK, forget it’ and walked away. But I thought if I keep hanging on and making these bloody awful records…”

As he made half-hearted attempts to climb back to the mainstream, despite every artistic instinct of his pulling him into the opposite direction, Scott Walker had slowly been cultivating something raw and sinister, thoughts occupied by despots and abstract snapshots of tragic myths. You can hear it in some of his early albums, on the dissonant drones of “Such a Small Love” or the alien production of “Plastic Palace People,” or the sleazy portrait of a family man consumed by his vices in “The Amorous Humphrey Plugg.” And you can definitely hear it on Nite Flights, an unlikely transformation and return of the Walker Brothers in 1978, inspired by Bowie’s Berlin albums and frontloaded with four songs written by Engel that revealed a kind of depth and depravity that even his strangest orchestral songs never did. “The Electrician” is a particularly horrifying account of an act of torture, inspired by Chilean dictator Augusto Pinochet and transformed into the stuff of J.G. Ballard erotica: “If I jerk the handle/You’ll die in your dreams/If I jerk the handle…you’ll thrill me and thrill me and thrill me.”

Walker had seemingly been revising the blueprint for an album like The Drift for decades, making his first breakthrough with Nite Flights, shaving his music down further on 1984’s Climate of Hunter, and weaponizing it on the divisive and caustic Tilt in 1995. Each of his returns seemed to happen after longer disappearances from the public eye, because, as he told the BBC, “If I’ve got nothing to say or do, it’s pointless to be around.” But seven of the 11 years after the release of Tilt were spent crafting the aural gauntlet of horrors on The Drift, not the first masterpiece in Walker’s career, but the one that definitively proves his greatest art is in building impenetrable fortresses of dread.

The second album in a trilogy of grotesqueries of sorts, preceded by Tilt and followed by Bish Bosch, The Drift is Scott Walker’s greatest recorded work. It’s an album of precise vision and violent dissonance, and though he had the sense of humor enough to joke about the cognitive dissonance on the title of Tilt‘s “Patriot (A Single)”, this is the album that seemed to shake any last vestige of commercial appeal out of system for good—and for the best. Even its cover art seems to warn of the bleakness within, as if someone let a copy of The Downward Spiral marinade in acid for a few days.

He doesn’t quite plunge the listener into the depths within the first song; “Cossacks Are” is tense and terrifying, as is everything here, but there’s a kind of urgency to its sharp cracks of snare and sinisterly snaking guitar riffs, with key lines from its lyric sheet drawn from newspaper clippings and book reviews. Walker’s humor likewise shines through here, with certain lines—detached from context—just as easily acting as reflections of his own work: “Has absence ever sounded so eloquent, so sad? I doubt it.” He offers a final wink into the camera (“That’s a nice suit/That’s a swanky suit“) before the album reaches its point of no return.

Walker designs a labyrinth of psychological horrors and jump scares alike, his elaborate and shrieking compositions owing more to the avant garde composition of Krzyzstof Penderecki and Gyorgi Lygeti than actual rock music. The melting facade of strings in “Clara” underscore its mythic and lurid narrative of Mussolini’s affair with mistress Clara Petacci before his eventual death and public mutilation with sticks and rocks. Walker’s sense of humor grows ever darker here, including percussion sounds made by the punching of a slab of meat, as well as a guttural grunt during one of the song’s pregnant silences. Though even in a piece as brutal as this, Walker appends it with a curiously tender coda about a swallow that flew into his room (“I picked it up/So as not to frighten it/I opened the window/Then I opened my hand“), as if to balance out the ugliness and violence with a moment of grace.

Scott Walker’s songwriting, here as it was with the Scott series in the late ’60s, is laden with dense layers of references that would require a bibliography to fully untangle, and even then they’re presented as snatches of half-heard dialogue and passing images. It’s less the studious attention to each thread that matters so much as the brutal details he pours into each song that brings an added gravity to the overall picture—cryptically communicated as it is. He makes a murkier permutation of the “Jailhouse Rock” riff the backdrop of “Jesse,” a juxtaposition of Elvis Presley’s stillborn twin brother and the September 11th terrorist attacks through an Eraserhead filter, climaxing with anguished moans of “I’m the only one left alive!” Braying donkey sounds punctuate the climax of the bizarre “Jolson and Jones,” and the water-torture percussion that persists throughout “Buzzers” only adds to the unbearable tension as Walker examines another war criminal, Slobodan Milošević.

There’s no natural light anywhere within the cloisters and ramparts of The Drift, just looming shadows and inescapable specters. But it does offer three brief minutes of relief in the form of its gentle, yet nonetheless strange “A Lover Loves,” composed of just Walker’s voice and acoustic guitar, his eerie vocal vibrato interspersed with strange repetitions of “pss pss pss.” “This is a waltz for a dodo,” he declares, after a strangely optimistic observation of “everything within reach.” As the final chord rings out, he whispers, “It’s OK.” You couldn’t easily picture this in the current top ten, but you might imagine drawing comfort from it in ways that most of the other songs here refuse to provide.

The brief, stripped-down approach to “A Lover Loves” in an indirect way feels reminiscent of “30 Century Man,” a likewise brief acoustic song on Scott 3, surrounded by much more elaborate and mood-heavy productions. In that song, Walker asks, “See the dwarves and see the giants/Which one would you choose to be?” He knew what his answer was, and despite all the trials and missteps and an aesthetic that was fundamentally incompatible with mainstream music, he wouldn’t settle for anything less.

Treble is supported by its patrons. Become a member of our Patreon, get access to subscriber benefits, and help an independent media outlet continue delivering articles like these.