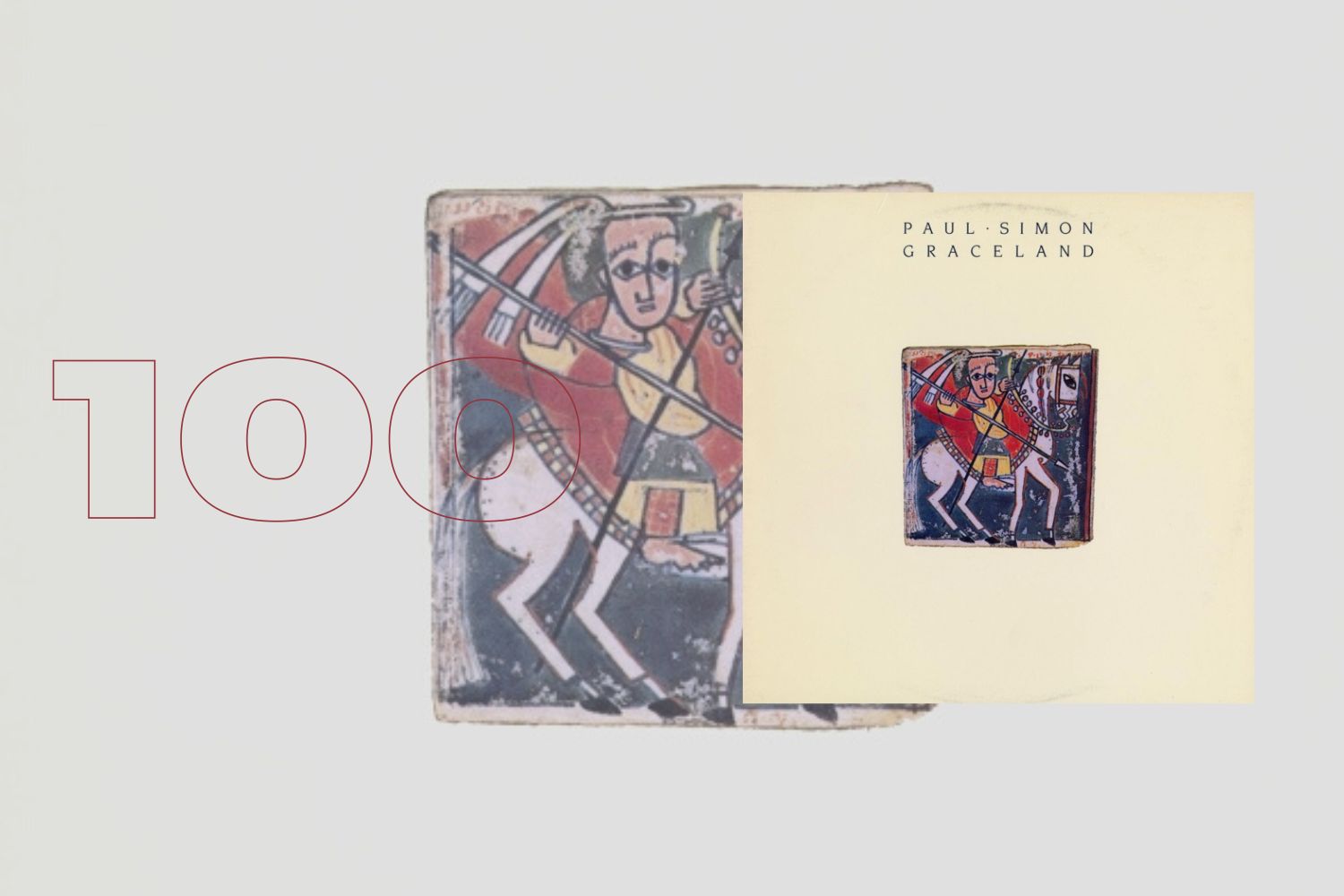

When my mother was in high school, she had a big poster of Paul Simon on the wall of her bedroom. Having grown up with the music of Simon and Garfunkel, my mom had acquired a teenage crush on the singer/songwriter, which naturally led her to pin up his face on the wall. Yet as time went on and the teenage crush faded, in the ‘70s onward, she retained a deep love for his music. And though I also share her love of Simon’s music, I have chosen, instead, to display the cover of his 1986 record Graceland—which I enjoy a lot more than the idea of the musician’s face staring at me in the dark while I sleep.

I don’t remember exactly when I first came across Simon and Garfunkel’s songs or albums—probably on some radio station, Big Oldies 107.3 maybe. But when it happened, I was hooked. So when I came across my mother’s copies of Simon’s Graceland and his follow-up, The Rhythm of the Saints (1990), I couldn’t drop the CDs in the changer fast enough. And because this was before streaming services, this collection of CDs (which included Joni Mitchell and Laura Nyro, among others) was the “suggested listening” I had at my disposal.

Simon and Garfunkel split in 1970 following their fifth studio album, Bridge Over Troubled Water—which won the 1971 Grammy for Album of the Year. Nearly 16 years later, Paul Simon was recovering from a divorce with actress Carrie Fisher and the relative commercial failure of his sixth solo release, Hearts and Bones (1983)—which actually was received pretty well by critics. But diminishing returns dictated that it was time for a new direction. One inspired by a bootleg cassette of mbaqanga, South African street music, from the Soweto township of Johannesburg.

This was the start of what would become his smash hit record, Graceland, which went on to win two Grammy Awards. However, at the time, recording in South Africa was strongly discouraged; the United Nations had imposed a cultural boycott for the country’s policy of apartheid. This directed writers, artists, and musicians to boycott it. Simon had initially said that the United Nations Anti-Apartheid Committee (ANC) supported his Graceland project, as it showcased black South African musicians and offered no support to the South African government, but the committee protested it as a violation of the boycott. And Simon was even added to the United Nations’ blacklist.

In 2013, Simon told National Geographic: “What was unusual about Graceland is that it was on the surface apolitical, but what it represented was the essence of the anti-apartheid in that it was a collaboration between blacks and whites to make music that people everywhere enjoyed.”

While the act of recording in South Africa itself was significant, the music is what continues to resonate—what stirs the bones and the hearts of listeners. Where he’d previously played the part of the pop icon, releasing hit singles such as “Kodachrome,” “50 Ways to Leave Your Lover” and “Slip Slidin’ Away,” his new endeavor was much more global. He had a Cajun twang and a Soweto rhythm inspiring his music.

Graceland starts off with the terrific “The Boy in the Bubble,” whose accordion and drums make for a dramatic, attention-grabbing introduction. Its lyrics are grandiose and prophetic, with lines like “These are the days of miracles and wonders” speaking to the world at large, rather than just the individual. Simon allows the music to be louder than usual, to almost drown him out occasionally. This is a big song, he’s telling the listener; and truly, this is a big album.

The rhythm in “Graceland” is still upbeat, but there isn’t a rowdiness present, with its blurred, reverberating guitar. Yet again, the song is a smooth one, riding along the vocal line as well as the backing instrumentals. Its title and lyrics are references the home of Elvis Presley, and it was inspired by an actual trip Simon took to Graceland after dealing with his then-recent marriage collapse. In “Gumboots” Simon takes up the Cajun twang once more, which works to great effect, giving a diversity in sound to his more direct pop sound. Its lyrics delve into both love and a breakup—a timely topic for Simon at the time—but without feeling tired or contrived. (This style is carried into his next release, which is specifically memorable in “Born at the Right Time.”)

“Diamonds on the Soles of Her Shoes,” which wasn’t originally slated to be included on Graceland, is the most prevalent example of Simon’s African musical influences. The song features guest vocals from the South African male choral group, Ladysmith Black Mambazo, who introduces the song before Simon switches back to his usual style. There is something wonderful about this break, or, really, breath before launching into the main body of the composition. It shows an artist stepping out of his comfort zone, playing around with structure. It likewise ends with Ladysmith Black Mambazo meditatively chanting and fading out.

That brings us to side B and my favorite track from the release, “You Can Call Me Al.” It became one of Simon’s biggest hits, thanks in part to its memorable video featuring Chevy Chase, which was a staple on MTV at the time. And though my mother likes to say Simon’s line “he ducked back down the alley with some roly-poly little bat-faced girl” is uncharacteristically cruel, perhaps it shows a lyrical honesty. I just find it sort of funny. In any case, the music itself is certainly engaging; it just keeps rolling and moving. Simon is able to keep the energy spinning and propels the song forward so well. Of course, having such great use of brass in a song always gets the foot stomping.

As to be expected with any great album, the second half album maintains the energy and strength of songwriting that’s introduced in the first. “Under African Skys” is the last track configured with an a Southafrican influence. Then comes another favorite (there are so many): “Crazy Love, Vol. II.” It also has an almost jungle vibe to it, maybe a touch like Joni Mitchell’s “The Hissing of Summer Lawns.” (More in atmosphere than style—Mitchell’s is a dark Henri Rousseau jungle, where Simon’s is much more upbeat with streaks of sunshine.) In it, he seems to be not only reflecting on his divorce but his own detachment in general (“Somebody could walk into this room and say, ‘Your life is on fire!’“).

His final two songs heavily return to his Cajun sound. “That Was Your Mother” and “All Around the World or The Myth of Fingerprints” are both fun, a bit silly. Both these songs held controversy from other groups—the zydeco band, the Good Rockin’ Dopsie and the Twisters, and then the rock band, Los Lobos, respectively—said they should be credited in the songwriting. But little of consequence happened following these disputes. Of the former sound, the track actually may remind you a bit of Simon’s 1973 hit “Kodachrome,” with its fast-paced rhythm and more immediate pop sound; one just uses accordion with the bayou tossed in whereas the other relies more on guitar and a wild west saloon feel. “All Around the World…” ends the album, once again bringing Louisiana to the listener’s ears. Joyful. Celebratory. Simon’s work is all about different forms of expression. And though suffering artists can charm, those can still translate that into joy can bring us together, and get us crowded around a radio or record player.

More than 35 years later, Graceland doesn’t sound tired or worn out. It is an album that I return to frequently, alongside Joni Mitchell’s Court and Spark, Laura Nyro’s Eli and the Thirteenth Confession, and Teaser and the Firecat by Cat Stevens. Is it Simon’s fullest achievement? There’s certainly an argument for that—as well as for it being one of the most iconic albums of the 1980s. But most significantly, it marks a massive shift in the career of a hugely talented, visionary musician and songwriter.

Treble is supported by its patrons. Become a member of our Patreon, get access to subscriber benefits, and help an independent media outlet continue delivering articles like these.