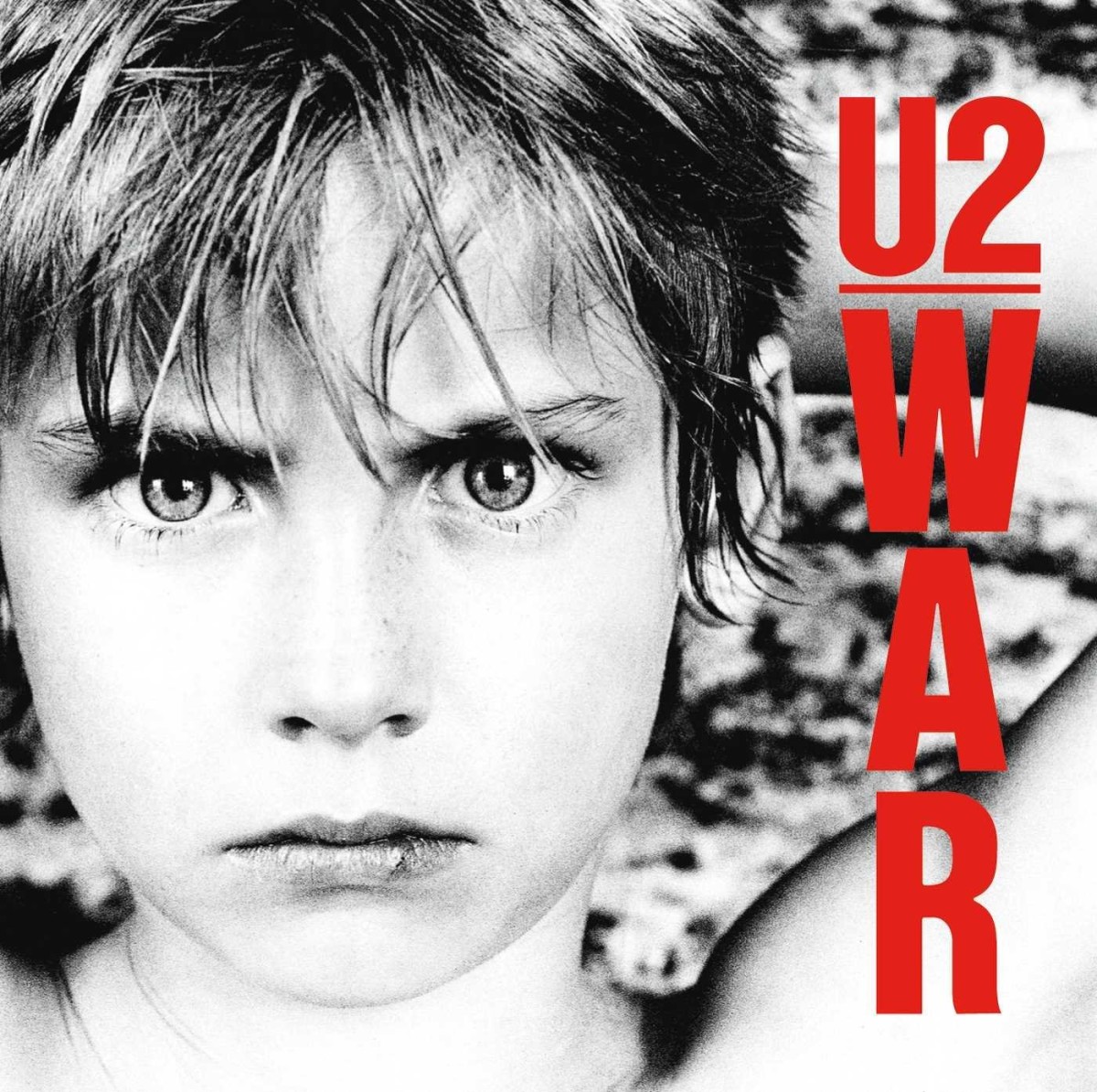

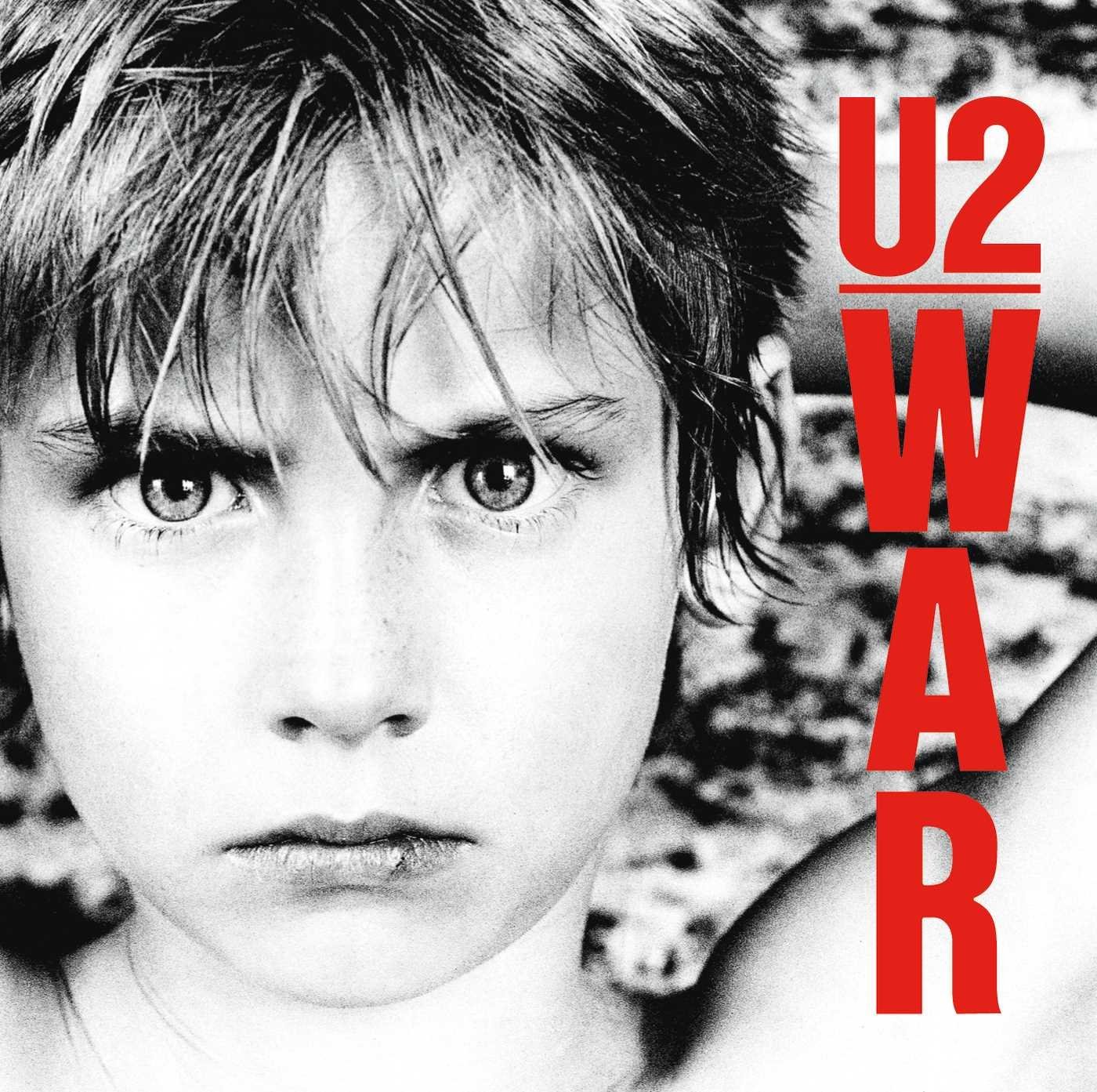

U2’s War provided a triumphant close to their post-punk trilogy

In viewing U2‘s work as a whole, the band’s albums seem to form a series of trilogies. That in itself is not an unusual thing for a band—The Cure have their goth trilogy, Bowie his Berlin trilogy and so on. Yet remarkably this occurs several different times with U2. The Unforgettable Fire, The Joshua Tree and Achtung Baby form the core of U2’s identity as one of the premiere rock bands of our time, big on both concept and stadium-filling anthems. And Zooropa and Pop, along with 1995’s Brian Eno collaboration as Passengers, finds the band embracing their freest art pop tendencies and most abstract indulgences.

The band’s first three albums, likewise, form a trilogy—a crucial one in their development, if one that’s by and large been shelved to history, not a forgotten chapter but one that they more or less “retired” outside of a handful of songs (“Sunday Bloody Sunday,” “New Year’s Day”) remaining live staples nearly four decades later. There are a few basic, simple things that 1980’s Boy, 1981’s October and 1983’s War have in common. They’re the band’s three earliest albums, written and recorded at a time when U2 as a concept—as a brand—had yet to become fully formed and establish its market value. They each have one-word titles. They’re also the only three albums in their catalog that are, stylistically, post-punk.

War is the dividing line between U2, the young Dublin new wave act and U2, the heroic stadium rock band. And in definitively closing the book on the latter, the group offered their hardest-edged set of songs in their catalog—two punchy, muscular sides of earnest rock music that retained a punk edge in spite of the fact that they were on the verge of being too big to be in the same sphere as punk. The punks, naturally, didn’t take to U2, and in the face of their cynicism about the band, the group offered up “Like A Song,” a counterpoint to punk’s self-defeating, surface-level gatekeeping backed by the darkness and abrasion that pulsed beneath the greatest moments on their debut album, Boy. “Too set in our ways to try to rearrange,” Bono sings. “Too right to be wrong, in this rebel song.”

U2 reportedly played it only once live and never looked back.

Whatever U2 purged of themselves with War, arguably the first U2 album to suggest the level of soaring heroism that would become their stock in trade, in doing so they pushed themselves harder than they’d ever gone. War is a loaded title for an album. It also captures both the state of the band and the state of the world with a clearer view than their two previous albums; Bono’s deepening interest in global affairs and conflicts—nuclear proliferation, the Polish Solidarity movement—was matched by a sound marked by heavier rhythms and sharper edges. The album opens with Larry Mullen Jr.’s heavy, militant drum work on “Sunday Bloody Sunday,” and though there are moments of levity and lightness, a sense of austerity pervades throughout the album.

War was also, by that point, the band’s best set of songs. And it remains one of the highest points in their canon, the document of a band shaking the uncertainty of their previous album and pushing forward with everything they’ve got. “Sunday Bloody Sunday” is one such song, inspired by the Troubles in Northern Ireland and driven by Mullen’s militaristic drumming. Like most of the songs here, it didn’t start out as political commentary—The Edge wrote the riff in a moment of personal frustration after fighting with his girlfriend, and after he brought the raw materials to the band, it was tightened up and infused with a sense of purpose. “How long must we sing this song?” Bono asks in a line that gets adjusted slightly in the closing hymn “40.” It becomes a refrain that speaks to nearly every topic explored throughout the album, whether it’s a civil war or nuclear saber-rattling.

“New Year’s Day,” the album’s most anthemic moment, retains the post-punk groove of Boy while adding some ghostly, echoing twinkles of piano, as if borrowed from Jamaican dub. Its video, depicting the band in a snowy landscape, mirrors its melancholy, but though this song, too, was notable for being one of the more politically minded songs on the album—Bono rewrote the lyrics after reading about the imprisonment of Lech Walesa, who years later would end up being elected Poland’s president—it began as a simple love song. Adam Clayton wrote its bassline while trying to figure out how to play Visage’s “Fade to Grey,” which feels right in context—lines like “nothing changes on New Year’s Day” make this one of the most goth moments in the U2 catalog.

While another year would pass before they teamed up with Brian Eno and began a journey into becoming something much bigger than they had already grown into, on War U2 confidently employed some unconventional directions in the studio. The Edge provided vocals on “Seconds,” one of only handful of tracks in the group’s catalog in which he’d do so, while Kid Creole and the Coconuts—a more vibrant and playful counterpoint to U2’s stark seriousness—provided backup vocals in the studio.

Most notably, the album’s final song came about almost as an afterthought. Clayton had already made his departure from the studio when Bono, the Edge and Mullen determined that the album didn’t have a proper closing song. What they came up with, “40,” is an epilogue more than an anthem. The track quotes from “Psalm 40” and returns to a chant of “How long to sing this song?”, echoing the album’s opening track in a new context. Written, recorded and mixed in under an hour, the song—though created on the spot—ended up becoming a staple of the band’s live show, with each member departing one by one before it’s over, Clayton—ironically—often being the last to leave.

The audience response to “40”—thousands of voices singing its refrain in unison, as captured on live EP Under a Blood Red Sky—illustrated the growth of the band not merely as a songwriting entity but as performers. On record, it might be songs like “Sunday Bloody Sunday” that hit the hardest (and, well, live too for that matter). But this? This is showmanship, an unapologetic play for immortality. War closed a trilogy, but it placed the band on a higher pedestal, the promise of becoming one of the world’s greatest rock bands all but fulfilled.

U2 : War

Support our Site—Subscribe to Our Patreon: Become one of our monthly patrons and help support an independent media resource while gaining access to exclusive content, shirts, playlists, mixtapes and more.

Jeff Terich is the founder and editor of Treble. He's been writing about music for 20 years and has been published at American Songwriter, Bandcamp Daily, Reverb, Spin, Stereogum, uDiscoverMusic, VinylMePlease and some others that he's forgetting right now. He's still not tired of it.