On ‘Another Green World,’ Brian Eno visited unimaginable new places

In 1975, the music industry was Brian Eno’s toy store. It had only been three years since his first professional credit, and yet he had already taken Britain by storm as the keyboardist and “treatments” guy in flamboyant sophisticates Roxy Music, ridiculing the infantile glam scene in the process. And that was just the start of it: He had subsequently left the band and recorded two colorful and idiosyncratic solo albums, made an impenetrable proto-ambient record with Robert Fripp, released a bizarre version of “The Lion Sleeps Tonight” as a single and served as executive producer on a solo album by one of his heroes: John Cale. And even that’s not an exhaustive list.

It’s no surprise, then, that when it came time to make a new album in spring 1975, he wasn’t afraid of trying something different. The formal confines of rock and pop song structures, as evidenced by his work with Fripp, had already begun to frustrate him, and his voracious appetite for pushing the boundaries of writing and recording techniques would lead him to release his first full-blown ambient album Discreet Music before the end of the year. Accordingly, Another Green World marks the moment when Eno’s almighty mind is evenly split between wanting to please with his music and wanting to experiment. It is one part pop music, one part avant-garde.

Eno settled down into the Basing Street Studios, the home studio of Island Records founder Chris Blackwell. It was an old consecrated church in the metropolitan Notting Hill area of London, and had played host to Bob Marley, Led Zeppelin and The Rolling Stones among others. He called some of his usual suspects, starting with Robert Fripp, who had just left King Crimson (the two swiftly made the Evening Star album the following winter, and worked together on Bowie’s Berlin trilogy). John Cale, an opposite force to Fripp in many ways, was next through the door. Cale was the more influential force on Eno’s musical philosophy—Eno had been a major Velvet Underground fan, and admired their mixture of rough simplicity and poetic artistry—but Fripp’s capability of offering a spontaneous moment of virtuoso improvisation was too enticing to resist. Phil Collins, at the time merely the drummer in Genesis, was recruited, as was bassist Paul Rudolph, who had just replaced Lemmy in Hawkwind. This bizarre gang rarely if ever played together, with Eno preferring to spend entire days focusing on one particular instrument, but they were brought together for post-production. That no recordings remain of such meetings is the saddest part of the Another Green World story.

Focusing on one instrument per day is only the start of it, however. Recording began without a bar of the album having been written, Eno instead preferring to experiment with the studio itself, in the faith that with such fertile minds present, something worthwhile would emerge. There are reports of microphones being swung from the high ceiling whilst trombones were being recorded, in homage to Steve Reich’s 1968 experiment, “Pendulum Music,” for example. Perhaps inevitably, for the first week nothing even remotely usable emerged. Collins is reported to have stormed out on numerous occasions, and even Eno conceded years later that it was “almost unmitigated hell.” The risk was significant for Eno—he still had some commercial profile, and at a time when many of his contemporaries seemed to be struggling to maintain their own artistic highs (Bowie was in the thick of his cocaine period, Bryan Ferry had transformed Roxy Music into a far more mainstream band, Marc Bolan had almost been forgotten), he felt he had something to prove.

In a crisis, Eno turned to his art school background. Having attended the Ipswich Art School as a teenager in the 1960s, he went on to study at the esteemed Winchester Art College, where he became obsessed with minimalist composers such as John Cage, and with the theory of cybernetics—the study of systems and controls and how they can be applied to human action. Eno was fascinated by how such theoretical systems could be incorporated into musical and lyrical composition, and together with Peter Schmidt, he devised his infamous Oblique Strategies cards. The set of (originally) 113 cards each has a sentence or phrase printed on it, carrying some instruction that is not directly linked to the process of writing or composing, but rather intended to force the reader to approach the act of creating from a new angle, thereby liberating themselves from their own psychological constraints. Eno, Fripp and Cale all agree that this was the turning point in the recording of Another Green World, and from there the album was complete within four weeks.

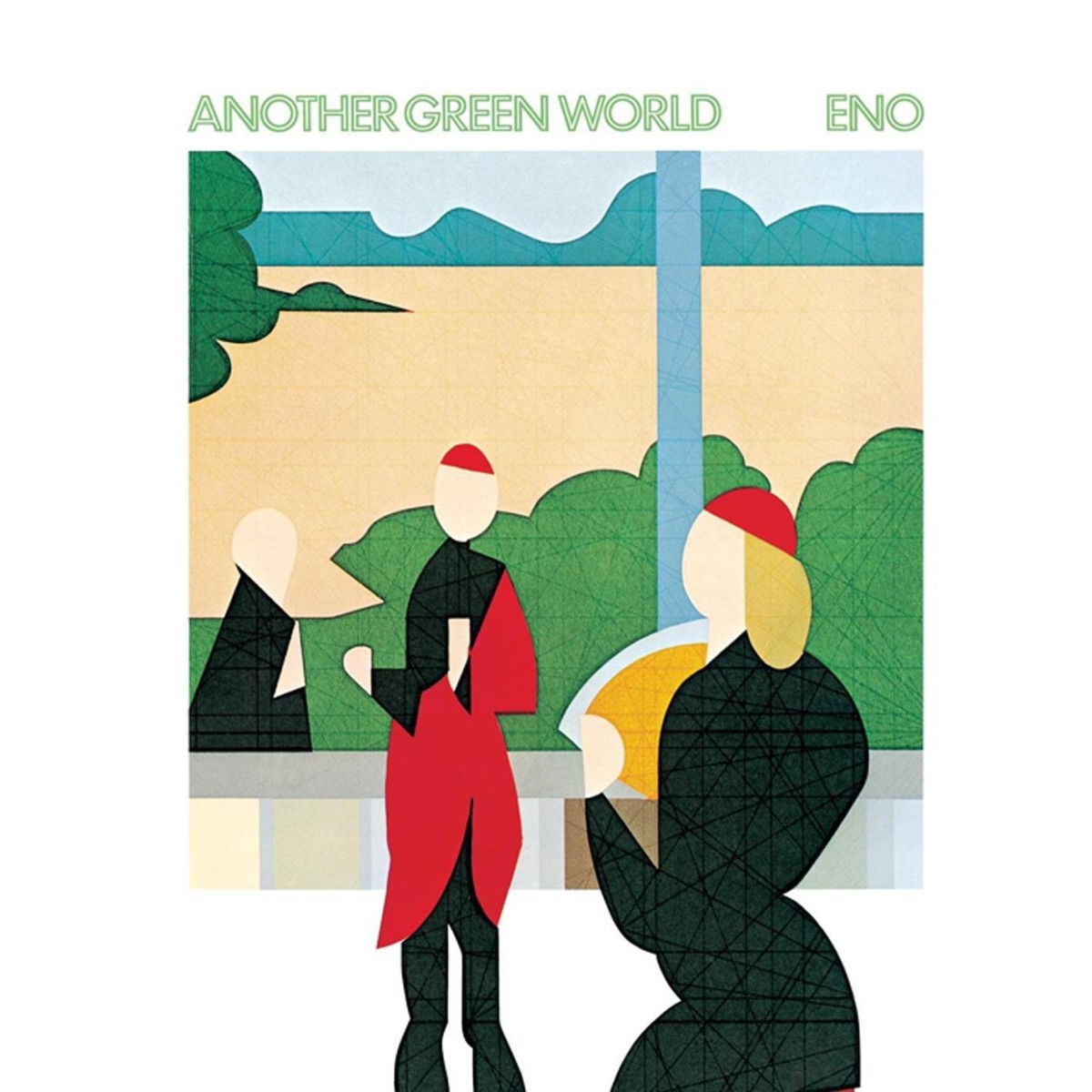

Despite such an eclectic cast of characters, Eno is the only credited musician on seven out of the 14 tracks on the album, most of which are among the majority of tracks in that they feature no lyrics. As Eno advanced ever nearer toward his full-blown experiments in ambient music, tracks such as “Another Green World” and the Tangerine Dream-like “Becalmed” are clear signposts for what is to come. The lyrics that are present were often derived from the Oblique Strategies cards, and as such are limited in their narrative meaning, but extremely rich in their suggestive imagery. From the album title to the cover art (created by Eno’s Ipswich art teacher Tom Phillips) to the track titles to the lyrics, everything about the album conveys images of a new world, seemingly discovered by our imagined protagonist. It’s a primitive yet familiar world, bursting with life, color and discovery. Unsurprisingly, Eno himself is reticent to comment on this, but when pushed by NME journalist Ian MacDonald in 1977, he articulated the “supreme irony that they left to find something new and unimaginable, but found another Earth-like place. It’s a loop, you can’t actually escape.”

To some extent, it can be viewed as a concept album. The early tracks depict the first encounter with the new world—”Over Fire Island” and “In Dark Trees” suggest trepidation (is this a hostile environment?). There certainly appears to be life. As it continues, we get “The Big Ship” and “Another Green World,” where fear turns to wonder, and the vast open spaces are somehow warm and inviting. “Sombre Reptiles” and “Little Fishes” follow, reassuringly, and by the end of “Zawinul/Lava,” there appear to be distant animals noises, not threatening, but rather crying for help. These tracks are all instrumental—the real storytelling on Another Green World is not found in its words, but in its music. In this respect, Eno is at his career high—his subsequent ambient albums asked us not to attempt to decipher meaning, or focus on the individual strands of music—but here the clues are there in abundance.

The album’s lyrical centerpiece, and perhaps the crowning achievement, is “St. Elmo’s Fire.” Its narrative matches the album’s tale of discovery (“We had walked and we had scrambled/Through the moors and through the briars/Through the endless blue meanders/In the cool August moon”), but the warmth of the song is in contrast with the still-dangerous alien place that the words imagine (“Well we rested in a desert/Where the bones were white as teeth, sir/And we saw St. Elmo’s Fire/Spitting ions in the ether”). The treated, clicking rhythms at the start are joined by a minimal organ part, providing just the sort of understated groundwork to accentuate the extraordinary, cascading, desert guitar solo to come from Robert Fripp. Eno asked Fripp to replicate the sound of sparks flying from a generator, the old romantic, and Fripp did not disappoint. As Eno’s plaintive, layered vocals re-emerge, Another Green World reaches its greatest height.

The other lyrical tracks, by comparison, are relatively standard. “I’ll Come Running” is the most conventional of them, and as such the most jolting. The almost Beatlesque naiveté is charming, and the repetitive sing-along second half provides the album’s most effective earworm, but it would be more at home on one of Eno’s previous records. Likewise, “Everything Merges with the Night” is a romantic tale, albeit with some suggestion that the third verse masquerades as a cryptic critique of the Chilean “socialist” experiments of the mid-’70s. Nevertheless, the inclusion of such standard pop/rock songs (very strong ones, too) gives the album the backbone that many of Eno’s fans, still clambering for another Here Come the Warm Jets, would have required in 1975. Eno would only once again be so charitable on a solo album, on 1977’s Before and After Science.

In Another Green World, you can see the blueprint for so much of what was to follow. The freeform ambient experimentation that Eno himself would pursue, the use of electronic sounds to depict organic landscapes and human emotions, the freedom from having to clutter every concept album with too much narrative, the avant-garde composing techniques, the combination of electronic and organic instrumentation—these are all commonplace in music in 2015, but were not before 1975. You can hear the roots of Radiohead, Boards of Canada, M83, Björk, Air and Portishead. You can hear the influence that Eno had on his contemporaries when you listen to Low, or Suicide or O Superman. But more than any of that, it is an accessible, peaceful, joyous album to listen to, and the best that Brian Eno has ever made.

Note: When you buy something through our affiliate links, Treble receives a commission. All albums covered are chosen by our editors and contributors.

Support our Site—Subscribe to Our Patreon: Become one of our monthly patrons and help support an independent media resource while gaining access to exclusive content, shirts, playlists, mixtapes and more.