10 Epic Opening Tracks

In the age of shuffle and curated playlists, the importance of an album opener might be negligible, but we still appreciate the art of the album, whether or not it reflects the music industry as we now know it. An opening track is, as far as the art of the album goes, very important—it needs to capture the listener’s attention, but it also sets the tone for the next 45 to 90 minutes of music. The best opening tracks can be brief introductions, hit singles, slow burners or barn burners. And, of course, it can also be incredibly misleading. (And sometimes it’s someone else’s song, bridging two artists’ worlds.) But sometimes they’re colossal. Indeed, some of the best album openers are those that go the distance—the songs that send the message that the album you’re about to listen to isn’t just entertainment, it’s an immersive experience. So we’ve assembled a list of 10 epic album openers that don’t have to be super long (though most of them are 10 minutes or longer) but definitely make for an epic listen.

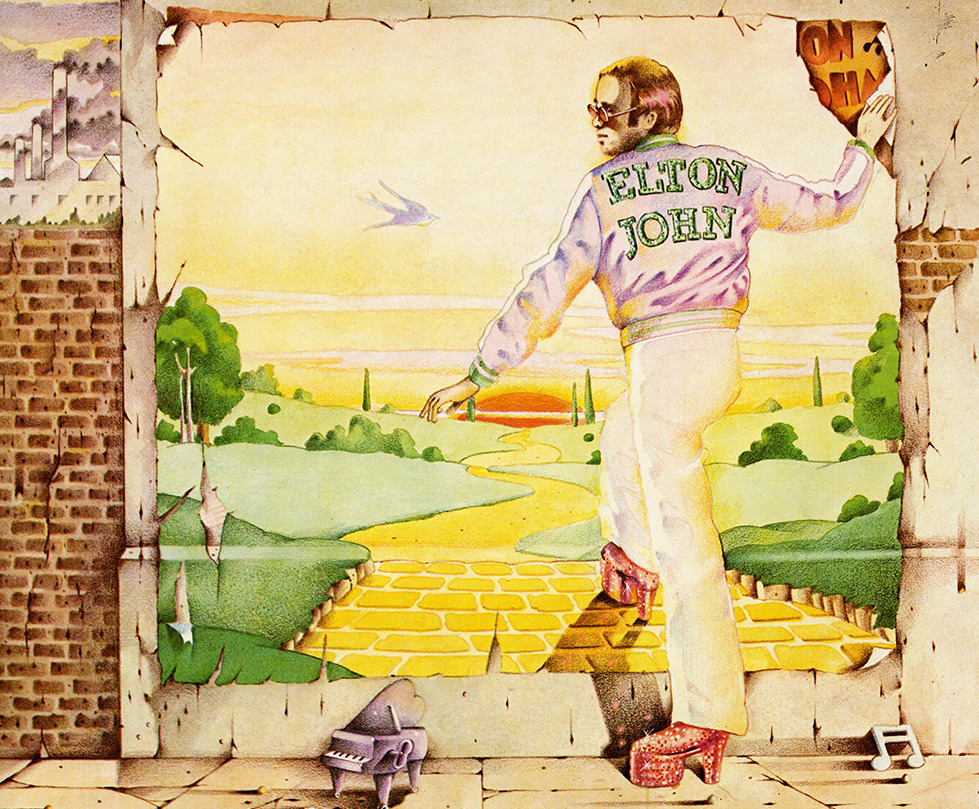

Elton John – “Funeral For a Friend/Love Lies Bleeding”

Elton John – “Funeral For a Friend/Love Lies Bleeding”

from Goodbye Yellow Brick Road (1973; MCA)

The sprawling two-part rock opera that kicks off Elton John’s 1973 double-album Goodbye Yellow Brick Road was a first of sorts for the singer/songwriter: his first prog-rock opus. And what an opus it is—a bombastic Moog intro, some heroic guitar riffs, an ever-escalating sense of drama and, ultimately, the big rock anthem that it continuously hints it’s ready to become. That rock anthem is arguably Elton’s best, as impeccable a feat of songwriting as he’s ever delivered, but with all the intensity and riffs of classic heavy metal. And it all happens in the ample space of 11 minutes, covering most of the double-LP’s first side. It’s a great pop song that also rocks hard, and it’s unapologetically over the top—as Elton John’s music often was. It’s no coincidence that both halves of this song’s title lent their name to an emo band and a black metal band. – Jeff Terich

Pink Floyd – “Shine On You Crazy Diamond (Parts I-IV)”

Pink Floyd – “Shine On You Crazy Diamond (Parts I-IV)”

from Wish You Were Here (1973; Harvest)

The opening sections of the suite enveloping Wish You Were Here find Pink Floyd forming a methodical sonic search party for their old bandmate, Syd Barrett. It matches their wailing and measured guitar work with majestic synthesized atmospheres suggesting German electronic pioneers from Schulze to Stockhausen. It’s a beautiful, sad, and quite purposeful departure from the cracked experimentation that brought them into the 1970s. – Adam Blyweiss

David Bowie – “Station to Station”

David Bowie – “Station to Station”

from Station to Station (1976; RCA)

In a career defined by sharp persona pivots, David Bowie’s Thin White Duke was especially enigmatic. He’d just come off his slickest ‘70s album, Young Americans, was lording over (and under) Los Angeles, on tenterhooks, and consuming enough cocaine to fill Tony Montana’s garage. While in this haze he managed an outstanding, deceptively sad album, Station to Station, that fed off its extraordinary title track. The Duke is a fatigued shaman, plugging along from—well, station to station, aware of the fact of his vacancy but disinclined to fix it. The first half of the song chugs in tedium as the Duke contemplates his withdrawal, referencing the Kabbalah: “Here are we, one magical movement/From Kether to Malkuth” (i.e., he’s a man who fell to earth). Indeed, “Station to Station” is a fuzzy register of some of Bowie’s favorite fixations: Crowleyism, the Kabbalah (via Crowley), the Stations of the Cross, Kirlian photography, lightweight suit jackets. When the song switches to mid-tempo disco, the Duke exposes his momentum as false but worth celebrating anyway: “It’s not the side effect of the cocaine/I’m thinking that it must be love.” (Spoiler alert: it’s the cocaine.) In the end he comes full circle and faces his own chill, realizing he’s milked his American experiment for all it’s worth and it might be time to book a flight: “It’s too late to be grateful/It’s too late to be late again/It’s too late to be hateful/The European canon is here.” Bowie thought Berlin was the kind of place where a disintegrating socialite could rejoin himself, and he was right. – Paul Pearson

Rush – “2112”

Rush – “2112”

from 2112 (1976; Mercury)

Stakes were high when the Canadian prog power trio recorded the side-long titular suite to their 1976 breakthrough album. Sales of their previous album, Caress of Steel, had been anemic. Mercury Records were sighing in annoyance and tapping their watches. Granted one more chance to save their careers, Rush hunkered down and constructed a 20-minute musical allegory loosely based on objectivist author and world champion scowler Ayn Rand’s brief novel Anthem. “2112” tears through nastily-inclined totalitarians like Alex Lifeson tears through Dean Markleys. The story writes itself. Dullard priests bluster, wayward man finds an abandoned guitar, teaches himself “Maggot Brain,” gives priests a PowerPoint on merits of said guitar, priests snort their derision, man shuffles home dejectedly, has a dream about simpler times, offers himself up as a martyr despite nobody really asking him to, and then faster than you can say “CSI: Syrinx” the exiled forefathers show up and boot those stuffy priest asses back down to entry-level positions in the mailroom. So if you’re ticked off about the invasive tendrils of theocratic fascism getting all up in your business, fear not: 94 years from now the Elder Race is gonna be all over that bitch. – Paul Pearson

Dire Straits – “Telegraph Road”

Dire Straits – “Telegraph Road”

from Love Over Gold (1982; Warner Bros.)

The 14-plus-minute opus that kicks off Dire Straits’ bleakest album depicts the lifespan of a British mining town, from the single, initial settler through accelerated growth and demoralized decline. Songwriter and guitarist Mark Knopfler broke the piece down into chunks that alternate moody brooding, workaday verses and frenetic umbrage. Much of the story is related through Knopfler’s instrument; that he navigates its mood through different melody structures instead of volume says a lot about his understanding. Keyboardist Alan Clark and drummer Pick Withers do a considerable amount of the heavy lifting. Even as the rises and build-ups are foreseeable from a distance, their execution is spotless. Lyrically, it’s actually under-written. Knopfler rushes through the middle stages as the town gradually displaces its innocence: “Then came the churches/Then came the schools/Then came the lawyers/Then came the rules.” But he and Dire Straits linger a long time in the Big Bang beginning and the gloomy, angry end. – Paul Pearson

Nick Cave and the Bad Seeds – “Tupelo”

Nick Cave and the Bad Seeds – “Tupelo”

from The Firstborn is Dead (1985; Mute)

Some consider the opening track on the Bad Seeds’ sophomore album a treatise on the birth of Christ as much as that of Elvis Presley and his stillborn twin Jesse. That’s debatable, but what can’t be denied is the power of Nick Cave’s seven-minute epic. From the now-iconic opening bassline by Barry Adamson to Cave’s horrifying exhortations for “mamas, rock your little ones slow” (fully aware of the ghoulish dead-baby implications) and the insistent tom-tom/guitar tandem that form the song’s engine, “Tupelo” is an easy contender for Cave’s best song ever and commands the entirety of your attention on The Firstborn is Dead. It’s a shame that the remainder of that album doesn’t come within approximately 100 miles of “Tupelo” and is in parts actively bad. But Cave would begin making cohesive, triumphant albums in just a few years (starting with Your Funeral My Trial), and “Tupelo” endures as a classic Cave track—the blueprint for later masterworks like “The Carny,” “The Weeping Song” and “Red Right Hand.” – Liam Green

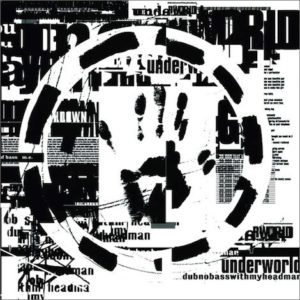

Underworld – “Dark & Long”

Underworld – “Dark & Long”

from dubnobasswithmyheadman (1994; Wax Trax)

You could argue that the sinewy “Juanita: Kiteless: To Dream of Love” from Underworld’s Second Toughest in the Infants should occupy this spot. Yet for critical impact I have to turn to this opener from their career-defining album two years prior. It’s an endless, subdued techno growl, from Karl Hyde’s mumbled lyrics of romantic obsession to the passing train of bass thumps and keyboards from Rick Smith and Darren Emerson. Remixed at least eight times and appearing alongside “Born Slippy” in Trainspotting, it also enjoys more public reach and recognition. – Adam Blyweiss

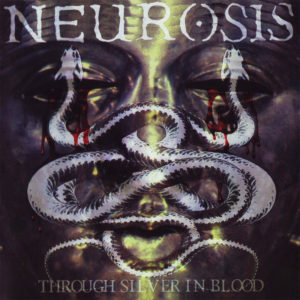

Neurosis – “Through Silver In Blood”

Neurosis – “Through Silver In Blood”

from Through Silver In Blood (1996; Relapse)

As regards song length, metal can go in either direction—on one extreme, the barely-there bombing runs of grindcore, on the other, well, pretty much any doom or sludge metal, and a hell of a lot of black metal if we’re being honest. In the ’90s, when Neurosis perfected the art of the apocalyptic sludge metal dirge, they were one of only a handful of bands at the time who made a habit of going the distance. And on Through Silver In Blood, it’s actually the more digestible tracks that are the rarities, with the title track’s opening progression like the long descent into their magma-filled caverns—the smoke-filled path toward the inner sanctum. With its volcanic riffs, industrial machinery samples and ominous build, it’s among the eeriest and most unsettling album openers of all time, yet it’s a powerful progression that remains gripping throughout its 12 harrowing minutes. – Jeff Terich

Yob – “Quantum Mystic”

Yob – “Quantum Mystic”

from The Unreal Never Lived (2005; Metal Blade)

Look, it’s almost unfair to include Yob in a list of “epic” anything, because they always take a little bit farther, soar a little bit higher and let it resonate even deeper. Yeah, Yob makes pretty epic music, though while their albums often end with something truly mind-blowing, it’s hard to name a more colossal opening track in their repertoire than “Quantum Mystic.” It’s a doom-metal anthem that lives up to its name, psychedelic and sprawling, a work of mystery and wonder that has the added benefit of kicking ass. At 10:59, it’s not the longest Yob song—not by a longshot (not even on that album, The Unreal Never Lived, for that matter). But it’s not the length that’s the defining factor here—it’s just how much of a journey exists within those 11 minutes. Be prepared to launch into the cosmos. – Jeff Terich

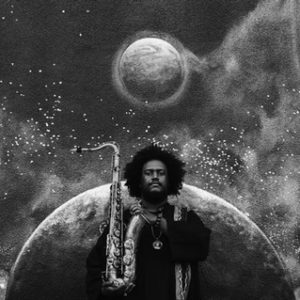

Kamasi Washington – “Change of the Guard”

Kamasi Washington – “Change of the Guard”

from The Epic (2015; Brainfeeder)

Well, it is the opening track of The Epic. Still, when Kamasi Washington kicks off an album, he does so with a sense of drama and grandeur. “Change of the Guard” was, for many listeners, the first listen to Washington period, so to hear the cosmic symphony that opens his triple-album Brainfeeder debut must have surely been an experience akin to some kind of spiritual awakening. It’s a 12-minute jazz cycle through orchestral and choral arrangements, magic cities, astral traveling and universal consciousness. An entire history of jazz can be heard within this track, and yet it’s such a singular, cohesive piece on its own, bringing decades of jazz influence into one powerful, sprawling track. That Washington followed this with another two and a half hours of similarly huge arrangements and gut-wrenching performances just reinforces why he’s one of the most important artists in jazz today. – Jeff Terich

Elton John – “Funeral For a Friend/Love Lies Bleeding”

Elton John – “Funeral For a Friend/Love Lies Bleeding” Pink Floyd – “Shine On You Crazy Diamond (Parts I-IV)”

Pink Floyd – “Shine On You Crazy Diamond (Parts I-IV)” David Bowie – “Station to Station”

David Bowie – “Station to Station” Rush – “2112”

Rush – “2112” Dire Straits – “Telegraph Road”

Dire Straits – “Telegraph Road” Nick Cave and the Bad Seeds – “Tupelo”

Nick Cave and the Bad Seeds – “Tupelo” Underworld – “Dark & Long”

Underworld – “Dark & Long” Neurosis – “Through Silver In Blood”

Neurosis – “Through Silver In Blood” Yob – “Quantum Mystic”

Yob – “Quantum Mystic” Kamasi Washington – “Change of the Guard”

Kamasi Washington – “Change of the Guard”

I have to correct an assumption Paul Pearson makes in outlining the opening track of the opening track on Dire Straits’ “Love Over Gold.” The story indeed tracks the arc of a town, from the first pioneer settlers, to post-industrial blight and beyond.

However, while Knopfler’s lyrics are designed to apply to a phenomenon in many, many cities and towns on both sides of the pond, he was not specifically describing an English mining town. Rather, his lyrics specifically describe the west side of Detroit, Michigan, and one of its real life thoroughfares: Telegraph Road.

Knopfler told the story in an interview in the late 1980s about how he was sitting in traffic on the bus after a gig in Michigan, and found himself wondering how this six-lane road came into being. Ever the history buff, Knopfler did some research to learn of the pioneers who settled Michigan in the early 1830s. What the lyrics describe is precisely the story of Detroit – from thousands of miles of original growth forest, to pioneer homesteads, to early American town, through it’s growth in the 1900s, to becomes the “Arsenal of Democracy” in the 1940s, to the place where the middle class was essentially invented thanks to the auto industry and its good-paying union jobs, to the race riots that in part precipitated its fall, to the influx of Japanese cars in the 1980s that all but sealed the deal.

I’m sure Mark saw so much of his native land in Detroit, especially the ship-building economies of Glasgow and Newcastle. If he ever thought to reprise the song, he would see that Detroit, like his own Jordie towns, have begun a long but solid rebound after hitting bottom … more than once. But if you’re ever in the Motor City, take a look at THE Telegraph Road after you visit the Motown Records Museum. And before you seek out Eminem’s 8 Mile. What a music town! 🙂