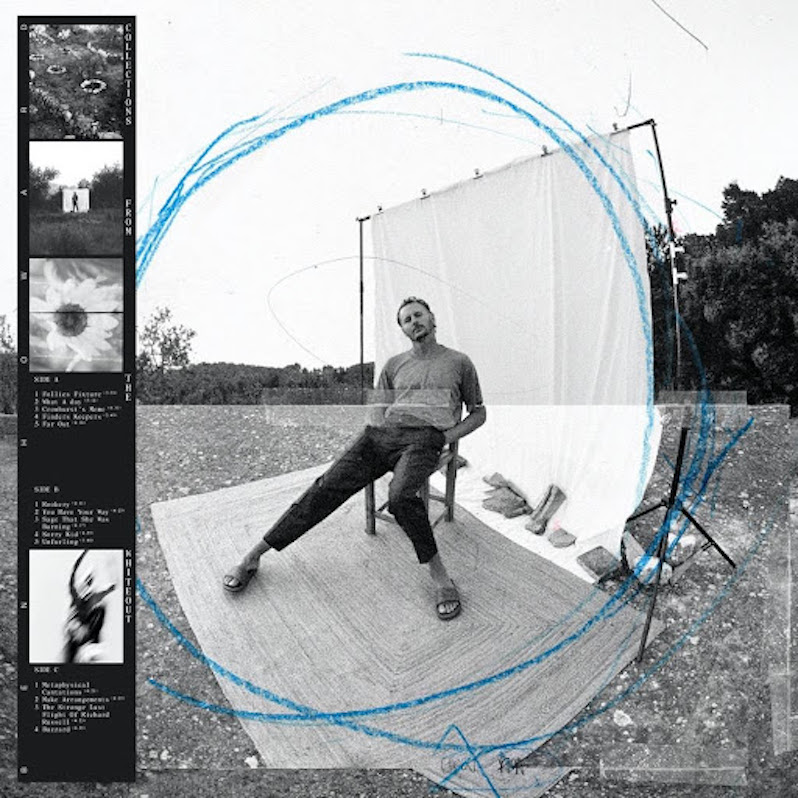

Ben Howard : Collections from the Whiteout

I went to see Ben Howard in concert a couple of years ago as he toured through Melbourne for Noonday Dream. He played the Palais, an old fully seated theater, and my frugal tendencies found me parked toward the back surrounded by a ragtag assortment of parents with teens, women on girl’s nights out and—a little bizarrely—what appeared to be some sort of corporate work event complete with fully suited attendees. As Howard and his band shoegazed their way through the lush atmospherics of his more recent material, the seats were filled with constant chatter, frequent trips to the bar and the odd shout of “Only Love!” or “do Keep Your Head Up.” In wholesale disregard of the “shut up and play the hits” crowd tendencies, ultimately not a single song from hitmaker debut album Every Kingdom made the setlist—a clearly intentional decision given Howard’s relatively limited catalogue, and one that reflects the deviation he and his music have taken and ensuing retreat from the spotlight since he burst onto the scene.

Far from this being a gatekeeping anecdote—what music people enjoy and how they enjoy it is their business (though c’mon people, enough with the talking during gigs)—it’s rather an insight into the way Ben Howard seems to be more remembered than known. Those paying attention, and probably paying more for front row seats, have seen him progress immeasurably, witnessing a profound creative evolution to a sound far more Slowdive or The National than those early Ed Sheeran comparisons. But despite this, he’s never quite been able to shake the image of the sunny young songwriter who belted out folk-pop summer anthems through festival season ten years ago. It’s a shame, because he’s developed into a far more interesting songwriter than even the potential those early songs offered suggested he would. In that sense, Collections from the Whiteout feels like a sort of excavation of all that Howard’s done until now. In many ways it goes back to his rootsy origins, but all the while fulfilling that obvious need he has to hollow out his sound and redress it in some way.

“I wanted to write a concept record, but I got distracted,” is how Howard playfully describes Collections. It’s not a bad summary. The record feels born of tinkered together fragments of ideas and experiments that somehow squeeze together into a fully formed whole, the thread of storytelling binding it together. The production of Aaron Dessner, the man Howard turned to to help develop his ideas—as so many seem to be doing—brings further fresh elements to the fold. It’s the first time Howard has branched beyond his inner circle and the Dessner effect is immediately apparent, not just for his own musicianship and production clout which are on clear display here, but also for the further connections he brings. Various prominent musicians, including members This is the Kit, Hiss Golden Messenger and Big Thief’s James Krivchenia provide a broader palette for Howard to paint with here as he embraces his inner troubadour.

These are tales spun from all manner of curious episodes gleaned from friends and news stories, unpacked with a heart of balladry that feels born of Celtic traditions. But on the edges, Dessner’s fingerprints are all over this. The flurried electronics that open the record on “Follies Fixture” and reappear intermittently throughout will feel immediately familiar to any fans of The National’s recent work. His influence is further spotlit in moments like the glitched static of curious little ditty “Finders Keepers”—about a body in a suitcase a friend of Howard’s father found in the River Thames—or the minimalist looped electronics and subtle atmospherics of “The Strange Last Flight of Richard Russell,” the disquieting tale of a man who stole and crashed a plane in Seattle. On the other hand, the anchored and understated melodies in the likes of “What a Day” and “Far Out” throw shades of earlier Howard efforts like “She Treats Me Well” or “Time is Dancing,” but find themselves elevated through off-kilter rhythms and unpredictable instrumental shifts. “Sage That She Was Burning,” one of the record’s best tracks in all the tension of its shifting dynamics and desperate vocal lines, is propelled by a captivating distorted electronic beat that shudders through a tale of a life lost to excess —snippets of the refrain floating through the mess, “half a life is half in dream.”

It’s a song that exemplifies the key to the record, that despite all the external influence, these crucially remain songs that feel distinctly Howard’s. Dessner has said as much, that for all the experimentation it was “important to also hear him in a very elemental way,” and in that sense Howard broadly eschews any semblance of melodrama that existed in previous efforts to focus on subtler melodic structures steeped in folk tradition. As any good storyteller does, he imbues his tales of inspiration with deeper universal overtones. The languid roll of “What a Day” is tempered by thoughts of wasted indifference in the face of death, “always fearing our hands up against the light, it’s nearing, where does all the time go?” While another of the record’s finest moments, the gorgeous folk melody in the stripped-back fingerpicked “Rookery” sees him throwback to the rookery of another of his best songs, Noonday Dream’s “Towing the Line.” Here we find him battling accompanying despair with those timeless blackbird images, “so hey that’s me, shooting at a hundred year old rookery. Oh look at me, the definition of futility, that’s what they’ll say anyway”.

It’s not clear what the titular “whiteout” is here, perhaps a reference to Earth’s circumstances over the last year, perhaps something else. But it’s a record that in many ways feels born of the uncertain nature of recent times. Scattered as it might be, Collections from the Whiteout feels nonetheless necessary for Howard. It doesn’t always work, there’s a distinct lull in the third act where several tracks feel somewhat incomplete—almost experimental filler. But he couldn’t have made another ruminant mood piece in the vein of I Forget Where We Were’s inner angst or the wistful soundscapes of Noonday Dream—probably still his finest hour—without it feeling played out. It’s hardly a momentous shift in sound, but the subtle change in focus and willingness to introduce new elements makes it adventurous in its own way. Certainly, back to back listens of Every Kingdom and Collections from the Whiteout will reveal two records canyons apart; and Ben Howard deserves to be remembered for where he’s reached, not just where he started.

Label: Island

Year: 2021

Similar Albums:

Hailing from Melbourne, Australia, Will has been contributing to Treble since 2018. Music and writing are the foils to his day job. Apart from Treble, he has contributed to Drowned in Sound, Glide Magazine and Indieshuffle. He also plays music and blogs when time permits.