Celebrate the Catalog : The Beatles

In The End…

Magical Mystery Tour

(1967; Parlophone/Capitol)

Even though The Beatles stopped playing live shows, they still wanted to be in front of audiences; in 1967 television seemed to be the most logical choice. The Magical Mystery Tour film is the result, a 52-minute piece shot in color and then awkwardly converted to black and white to reach the most fans. The accompanying LP was actually only an LP in the U.S., where the six tracks from the movie were grouped with five recent singles. However, in 1987 the LP was embraced as an official part of the Beatles catalogue, and rightfully so. MMT is a warm companion to Sgt. Pepper’s, continuing the traveling circus motif with orchestral instrumentation and a mix of lethargic psychedelic rock and some of the most iconic singles of their career. George Harrison gets one spotlight on Magical Mystery Tour, the cello-heavy “Blue Jay Way” finding his vocals distorted in an aural dream-sequence effect. “I Am The Walrus” is another standout; despite the campy chorus, Lennon pulls off verses that foreshadow the desperation and pain he would mine and perfect on 1970’s Plastic Ono Band. “Hello, Goodbye” and “All You Need Is Love” are the two singles most deeply imbedded in our zeitgeist, but “Strawberry Fields Forever” is a dazzling psychedelic experience that captures the studio-era Beatles’ desire for a more intimate connection with fans; offering them a journey they could begin as soon as the needle dropped. – Donny Giovanni

Rating: 8.5 out of 10

The Beatles

(1968; Parlophone/Capitol)

The White Album is the most successful transitional album ever made. Here are the Beatles at the onset of their fall-out. At this point, participation in the proceedings was optional; Ringo even quit temporarily in the middle of recording. The Beatles contains more flippancy, pound-for-pound, than any non-soundtrack project the band made. Paul’s song-writing floated between stark raving mad and music-hall indulgent. John’s acrimony was at full boil, even as he created the most emotional song in his catalog that didn’t call for primal scream. George felt helpless, or too disinterested, to effect change.

There is no center to the White Album – it gives in to the fissures that sprung from the exhaustively artistic Sgt. Pepper’s and its hung-over, marzipan stopgap Magical Mystery Tour. It’s a stylistic brawl; whether they were so brazen and confident that they’d do anything, so desperate that they needed to prove their versatility, or so fuck-all that they weren’t just going to halfheartedly fling out a single disc of mania. Nope, you got two records of dysfunction, plus the amateur art of “Revolution 9” as the toy surprise that nobody wanted. Christ, even Clapton shows up, like a pizza delivery guy.

This all makes it as vital an album as the Beatles made. Despite the unifying nature of the title, The Beatles showed the first flashes of the very individual personas they would, by necessity, adopt full-time two years later. Paul seems the most obviously schizophrenic, handling the very ordered pop of “Honey Pie,” “Blackbird” and (all apologies) “Ob-La-Di, Ob-La-Da” in the same breath as “Helter Skelter,” still the most deranged track he ever made. George’s possible tell-all “While My Guitar Gently Weeps” reconfirmed his stance as an outsider, straining for the empathy he’d eventually master with his solo masterpiece All Things Must Pass. John at first seems the most distant, straining for shock and bile with “Happiness Is A Warm Gun,” “Sexy Sadie” and “The Continuing Story of Bungalow Bill.” But his memorial “Julia” diffuses every last one of his defense mechanisms, whether it was the pissed-off teddy boy, the word-playing smart-aleck or the distempered mutineer – in just under three minutes, he makes it okay to be a vulnerable icon.

The Beatles made two albums under the pall of downward spiraling chaos: this and Let It Be. The White Album managed to find the vigor in the madness, the first few scraps of independence that comes from questioning everything they’d yet accomplished. It declines to make a statement and says everything that comes into their heads, their last great shot of id before their official beatification. It’s cocky, barefaced, and the only times the Beatles were ever fearful or terrifying (“Helter Skelter,” “Piggies,” and for reasons I can’t explain, “Good Night”). The end and “The End” were still a ways off, but on The Beatles, you could hear them splitting in four. – Paul Pearson

Rating: 9.1 out of 10

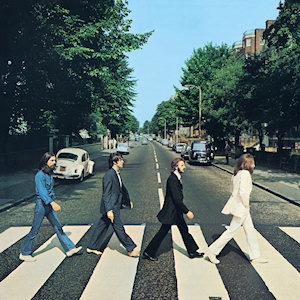

Abbey Road

(1969; Parlophone/Capitol)

Here’s what it really boils down to: Statistics. Look at the song lists of each of The Beatles’ albums. Look at how many songs from each album you could identify on sight, by name alone, as songs you might know and enjoy. There are a few albums where the band bats 1,000: Sgt. Pepper’s, of course; probably Rubber Soul and Revolver as well. For music recorded during the final tumultuous period of the band’s history — the notorious Let it Be sessions actually came first, for example, and John Lennon doesn’t appear on some songs — the Fab Four ultimately go 17-for-17 on Abbey Road.

It matters little that some of these songs might be fragments, even unfinished. Many of those are pieced together in the “Sun King” medley that takes up most of the album’s second half. They form a prime example of how the band members, even individually, could use their talents and the production facilities/pros at hand to create memorable sound. It finds The Beatles effectively spinning shit into gold, replete with some of their most memorable multi-tracked harmonies, the only Ringo Starr drum solo in their catalog, even a lyric turned into long-lasting philosophy: “And in the end, the love you take is equal to the love you make.”

This all comes even before any discussion of some of the most significant songwriting and performance contributions from Starr (“Octopus’ Garden”) and George Harrison (“Something,” “Here Comes the Sun”), Paul McCartney’s divisive, macabre pop number “Maxwell’s Silver Hammer,” and Lennon’s resurgent psychedelic blues (“Come Together,” “I Want You [She’s So Heavy]”). Abbey Road wasn’t the first time the Fab Four seemed to be solo artists merely working in the same place at the same moment, yet they somehow managed to bring together specific strong ideas more consistently here than on any other album. – Adam Blyweiss

Rating: 10 out of 10

Let It Be

(1970; Parlophone/United Artists)

If we’re being honest, Let It Be has a bit of an identity crisis. In Paul McCartney’s original vision, the sessions were a ‘back to basics’ attempt at live band recordings. In theory, The Beatles would record an album titled Get Back for a mid-1969 release. It was, in Paul’s mind, a therapeutic antithesis to the tense, disjointed, and often violent, sessions for The Beatles. After the sessions took a turn for the disastrous, that record was soon abandoned. Many of the best concepts from those sessions resurfaced on Abbey Road, but the rest became the band’s ironic swan song of sorts, in the form of Let It Be. Let It Be also falls in the category of Beatles albums directly tied to motion pictures, since the album served as a soundtrack for the similarly titled documentary on the band’s final years.

With all these different angles going into Let It Be, it’s not difficult to be disappointed by the end result. The album is oddly straightforward — the only late Beatles album completely void of experimentation. And, thanks to Phil Spector’s over-production, the record even lost its back-to-basics feel. His sappy choral and orchestral arrangements further deteriorated the final cut, completed after the band had already broken up. Even McCartney’s vision of reconciliation for the band failed. The sessions closely mimicked the atmosphere of The Beatles sessions, with tense arguments resulting in George Harrison quitting for a brief time.

Still, there’s something strangely enchanting about the tracks on Let It Be. One listen to McCartney’s re-worked Let It Be… Naked proves that, even in their lowest moment, The Beatles were still songwriting champs. “For You Blue” is a fantastic Harrison original, clearly written around the same time as his masterpiece “Something.” “The Long and Winding Road,” and “Let It Be” are both strong ballads. Others, like “Dig a Pony,” “I’ve Got a Feeling” and “Get Back” recall the sing along exuberance of early Beatles compositions, with a rustier, bluesy feel.

While Let It Be might not have been the perfect note for the band’s output to end on, it’s not a complete let down. After all, McCartney’s little experiment was actually successful, to a certain extent. The time and energy invested in the Get Back sessions might not have been immediately fruitful, but that era saw the Fab Four planting the seeds necessary for their magnum opus, and true swan song, Abbey Road. So, perhaps it’s best to think of Let It Be as an unflattering photo of the band’s last growth spurt: Awkward, indeed, but beautiful all the same. – A.T. Bossenger

Rating: 8.6 out of 10