History’s Greatest Monsters: The Rolling Stones – Dirty Work

“History’s Greatest Monsters” is a regular evaluation of albums deemed some of the worst in history. We do this not for the sake of schadenfreude, but to try to understand how these reputations were earned. Certainly, there are bound to be pleasant surprises. And certainly, there will be some truly unpleasant experiences in the months ahead. But we’ll all be better people for it, and hopefully we will have all learned something, and had a good laugh. Periodically, we will publish a Progress Report, to recap just where all of our candidates stand on the hierarchy of bad music, if they do at all.

The Rolling Stones – Dirty Work

As much as I’m glad the “What people think I do” meme has come and gone, it, to some of us, offered a good navel-gazing opportunity for those of us who sometimes wonder how, professionally, others perceive us. Generally speaking, most people tend not to have too many irrational assumptions about your professional identity, unless you’re a banker or a personal injury attorney. When I tell people I’m a music critic, they usually have a pretty good idea about what that entails, namely that I spend a lot of time in front of a computer screen and get a lot of free stuff. Sometimes I’ll get a polite dismissal from those who don’t value writing about music, and I’ve on occasion gotten an “I don’t pay attention to music,” as if to cut off any discussion whatsoever. And that’s perfectly fine — discussing your job is usually just small talk anyway, though ixnaying music means cutting out a good-sized chunk of conversation material.

Yet sometimes people use knowledge of what I do as an excuse to talk about their own weird obsessions. About seven years ago, I made the mistake of telling the husband of one of my wife’s co-workers about being a music writer, which he then read as permission to begin talking, for the next few hours, about why the Rolling Stones were the best band in the world. For the first half-hour and glass of wine, I humored him. For the next half-hour (and next glass of wine), I continued listening with mild amusement. But somewhere around two hours and four drinks in, I had to start tuning him out, once he had transitioned into accusing The Beatles of writing children’s music, or repeatedly (rhetorically) asking about whether or not Rolling Stone’s claim (back in 1980 I imagine) that The Clash were “the only band that mattered” had any merit. I’m not sure what the rules are about mansplaining to another man, but I’m pretty sure that’s exactly what happened.

Here’s the thing: The Rolling Stones are, or at least were, a great band. And the streak of Beggars Banquet, Let It Bleed, Sticky Fingers and Exile on Main Street is more or less perfect. But the Stones, whose 45-plus-year history and endurance is a feat in itself, are not perfect. Far from it. In fact, barring maybe Tattoo You, it’s probably best to forget they even existed in the ’80s (or the ’90s, or the ‘00s). And the Rolling Stones, themselves, would likely prefer to forget they ever made 1986’s Dirty Work.

In the 1980s, The Rolling Stones were also undergoing a “What people think I do” identity crisis. For nearly two decades, the Stones had established a singular sound, one that had been very successful for them, but it also may very well have resulted in creative stagnation if they didn’t make an effort to shake it up a bit. With albums like Emotional Rescue and Undercover, the Stones had attempted to remain contemporary by temporarily transitioning away from their patented gritty blues-rock, and instead adopting the glossy disco sound so prevalent at the time. Likewise, Keith Richards, a long-time fan of reggae, saw fit to start actually writing reggae songs, against his better judgment. (He also let Peter Tosh stay in his house in Jamaica, which backfired when Tosh and his entourage refused to leave.) Property-ownership mishaps aside, the Rolling Stones were basically subject to the same dilemma that had befallen every other artist of the ‘60s and ‘70s: How does an artist stay contemporary without abandoning its identity?

There are plenty of right answers to that question — David Bowie’s newest album The Next Day, any of Tom Waits’ albums from his Island Records days onward — but Dirty Work isn’t one of them. Sandwiched between two solo albums by Mick Jagger, Dirty Work marks the dot on the timeline at which Mick and Keef were no longer harboring much of a creative partnership. During many of the sessions, Jagger hadn’t even bothered to show up at all, showing little to no investment in the project, while drummer Charlie Watts likewise hadn’t been around much due to recovery from drug and alcohol addiction. So the album, essentially, is a Keith Richards and Ron Wood joint, and while that doesn’t necessarily wholly account for why it fails, it’s at least a significant contributing factor.

To be clear, Watts’ absence is a more noticeable hindrance to the album. It’s no secret that big-budget ‘80s production values sucked a lot of the muscle and grit out of otherwise interesting and powerful artists, and the plastic snap to the beats on every track is a dead giveaway of the era in which Dirty Work was produced. The album obviously sounds crisp and clean, and probably cost a fair amount to make. But the Stones always sounded much better when they got a little dirty, and Watts’ drums were frequently the warmest, most organic part of the Rolling Stones’ sound.

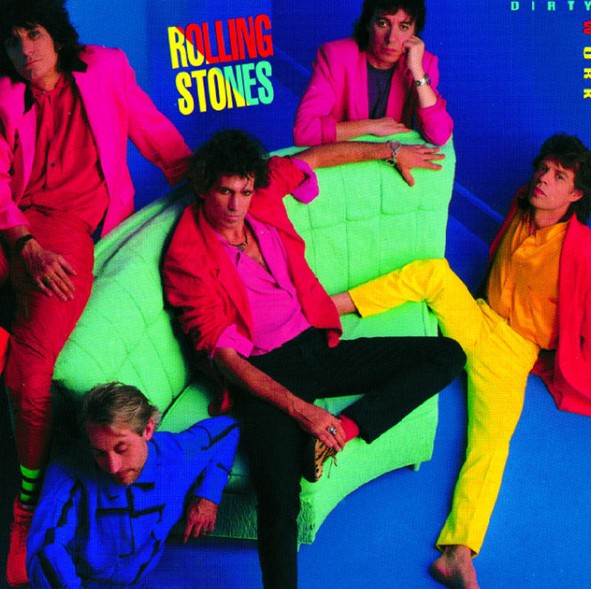

But Dirty Work, despite being filtered through ‘80s pastel and neon (just look at that cover, yeesh!), is still actually pretty dirty. Not sexually dirty — noisy dirty. Keith Richards’ guitar tone is more distorted and abrasive than ever, which is compounded by Jagger’s vocal performance, which is essentially all screaming all the time. He abandons the strutting sex god of yore, resorting to an unhinged, relentless bark, and while the glimpse of gloss in opening track “One Hit (To the Body)” might make Dirty Work initially seem like the Stones are mostly letting the studio do all the work, the strange contradiction is that they’re basically just screaming and making a lot of noise. I mean, what the fuck is even happening on this record?

The Stones are giving a phoned-in performance to some degree, mostly on the back half of the record, which lines up four Stones-by-numbers and knocks them down, via screaming into expensive equipment no doubt. But those frustrated by the band teetering on the fence for most of the second half of the album get a decisively awful final track in Richards’ ballad “Sleep Tonight,” which sounds like a drunken lounge act. It’s safe to say that even Keith was throwing his hands up and saying “Fuck it” by this point.

Not that the first half is by any means good. It’s… better than the second half. But that’s also a bit like saying Scary Movie is better than Date Movie. Maybe it’s true, but the argument is hardly even worth having. “One Hit” and “Fight” are decent enough, and of course, bizarrely noisy. A cover of “Harlem Shuffle” (not “Harlem Shake,” kids) is a sub-bar-band throwaway that reminds me of nothing so much as the Flaming Moe’s montage in The Simpsons. And a cover of Lindon Roberts’ “Too Rude” serves as yet another reminder that Keith Richards should stay far, far away from reggae.

On the surface, at a safe distance, if you squint your eyes and don’t listen too hard and think about ponies and cupcakes, Dirty Work seems like a typical Rolling Stones album. And it probably is, if you look at it ingredient by ingredient. But those ingredients don’t mix right, the outside is overcooked, and the middle is still frozen. And since I already backed myself into a cliche food metaphor corner, I might as well just go there: Dirty Work is a shit sandwich.

Final Grade: F

Jeff Terich is the founder and editor of Treble. He's been writing about music for 20 years and has been published at American Songwriter, Bandcamp Daily, Reverb, Spin, Stereogum, uDiscoverMusic, VinylMePlease and some others that he's forgetting right now. He's still not tired of it.