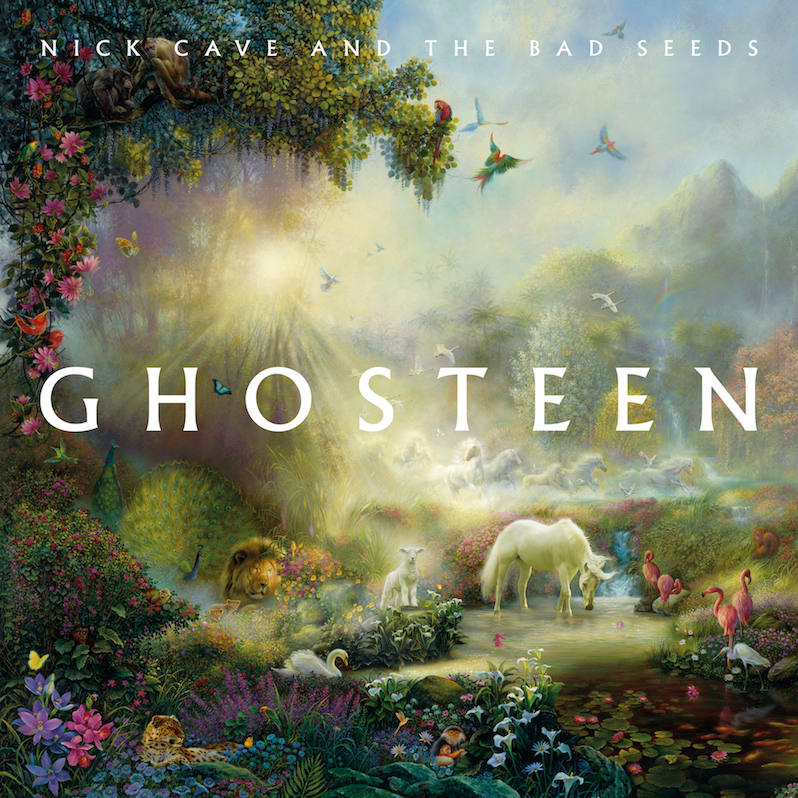

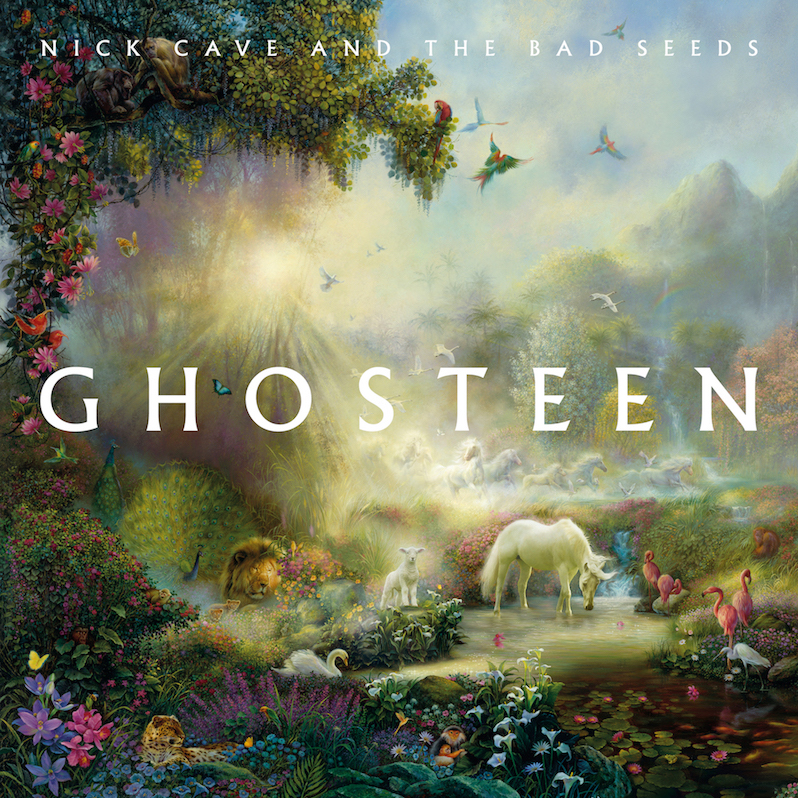

Nick Cave & the Bad Seeds – Ghosteen

Nick Cave‘s always been a storyteller, but for much of his career those stories weren’t necessarily his own. He delivered trash-culture retellings of Shakespeare and the New Testament. He reinterpreted American blues and folk tradition in more grim and shocking ways. And he created a definitive pop song depiction of the devil that, after 25 years, remains a staple of popular culture. It wasn’t until 1997’s The Boatman’s Call that Cave finally opened up the pages of his own biography, a brief but now-famous chapter in which he had a romantic partnership with PJ Harvey. It revealed a vulnerability and tenderness that, while not entirely alien or unfamiliar to his songwriting, proved rare in the context of the folklore and legends that populated his body of work.

For the past two years, however, Cave has been making a greater effort than before to give more of himself to his audience. He’s embarked on several rounds of touring of a show called “Conversations,” which finds him opening up the floor to any questions that the audience cares to ask. Sometimes they’re deeply intimate, and sometimes they’re about pizza—and sometimes the entire experience can be a little awkward—but it’s an effort toward a greater connection, and one that performers scarcely offer up so readily. And for those unable to talk face to face to the Australian artist, he’s launched The Red Hand Files, a regularly updated Q&A blog in which Cave has addressed everything from body image to how one should square Morrissey’s songwriting abilities with his right-wing politics. He also addressed the death of his son Arthur in a poignant entry last October. “It seems to me that if we love, we grieve,” he writes. “That’s the deal. That’s the pact. Grief and love are forever intertwined.”

Cave’s beautifully dark 2016 album Skeleton Tree, released one year after Arthur’s death, ostensibly felt like his own response to that grief, his way of working through the pain of losing his own child. Most of the album was written much earlier, in fact, but the specter of such a tragedy became intertwined with the album’s expressions of loss: “I called out, I called out/Right across the sea/But the echo comes back empty.” Its follow-up, Ghosteen, is the first proper album that Nick Cave & the Bad Seeds have written since Arthur’s passing—the third entry in what Cave has described as a “trilogy” that began with 2013’s Push the Sky Away—and it’s the prettiest, most delicately devastating album they’ve ever released.

Ghosteen is an album that seeks to find light and warmth in the depths of one’s own personal grief. For much of the entire first half of the album—which is split into two halves, part one being “the children” and part two, “the parents”—Cave is seemingly afloat in a gentle, surreal kind of ambiance. The sounds are soft and comforting, worlds apart from the punishing piledriver bass of “The Mercy Seat” or the sinister elegance of “Red Right Hand.” They’re not meant to hide the anguish, but rather to give space to grieve. Just as Cave has put himself out more in front of his audience as a real, genuine person rather than merely a performer, he’s invited listeners into a space more personal and intimate than before, and it’s heartbreaking. The gentle piano of “Bright Horses” provides an eerily gorgeous backdrop to his own meditations on the ghostly visions before him, and the need to see things other than as they are: “And the little white shape at the end of the hall/Is just a wish that time can’t dissolve at all.” Most of the songs that comprise the half that Cave dubs the “children” are the most fantastical and abstract, rife with imagery of “butterflies and the fireflies, and the burning horses and the flaming trees” as he describes in the sublime “Sun Forest.” Cave revisits a favorite topic, Elvis Presley, to examine his own eventual mortality and legacy in opener “Spinning Song,” And on the part one closer “Leviathan,” Cave looks perilously into the literal abyss, parked on a cliffside, repeating the mantra, “I love my baby and my baby loves me,” constantly revisiting his own source of comfort and compassion while faced with a pain he can’t let go.

The “parents,” by contrast, feel more corporeal and earthly. Two lengthy compositions bridged by a spoken-word piece, they build an orchestral expanse of acoustic and electric instruments around the recurrent synth glow that permeates the album’s first half. They’re also more explicitly steeped in the feelings of “grief and love forever intertwined” that he previously spoke of. The title track is an absolute masterpiece of melancholy beauty, featuring the only proper climax of the album’s 68 minutes. A string section, live drums and what seem like countless layers come crashing in after the first verse, underscoring a kind of hallucinatory visitation from the wandering spirit its title connotes. But it doesn’t stay there long; over the next six minutes Cave begins to wander, himself, from a mundane if quietly crushing narration of washing his son’s clothes (“Love’s like that, you know“) to the declaration that “There’s nothing wrong with loving something you can’t hold in your hand.” As the other parent in the pairing, “Hollywood” is at once bleaker and wiser—it’s the rare track in which a feeling of terror begins to creep in amid the sadness, an ominous bass loop throbbing beneath Cave’s travelogue down the Pacific Coast and visions of a “kid with a bat face.” But two full verses are dedicated to a Buddhist parable that teaches a profound lesson about death and loss: Kisa Gotami, desperate after losing her own child, seeks counsel from the Buddha, who tells her to collect mustard seeds from houses where no family member has died, and that will bring back her child. She doesn’t succeed, “Because every house, someone had died.” The moment in which we feel the most alone, the most isolated and wounded, is the thing that, ironically, everybody shares.

Ghosteen is credited to Nick Cave & the Bad Seeds, even though the arrangements are some of their starkest. Initial reactions led to speculation that only Cave and longtime musical partner Warren Ellis had actually performed on the album, though Thomas Wydler, Martyn Casey, Jim Sclavunos and George Vjestica all take part in these atmospheric, mystical compositions. If it doesn’t feel like a full-band effort, listen a little closer, in the glorious backing vocals on “Ghosteen Speaks,” in the gradually more penetrative bell tones in “Night Raid,” in the momentary climax of “Ghosteen” or in the percussive, creeping darkness of “Hollywood.” Cave has always been given a more powerful platform built on the contributions of his collaborators, and though they adapt to a different role here, they’re still supportive, still the crack team of ringers that can turn both a set of punk-blues freakouts and a double-album’s worth of ballads, dirges and lullabies into something transcendent.

At the end of closer “Hollywood,” Cave sings, “It’s a long way to find peace of mind,” and it’s clear that there’s still some miles to go before he gets there. There’s no closure, no climax, not much of a resolution at all. If anything, it ends in ellipses, an acknowledgement that the messy mixture of love and grief that Cave so eloquently described simply stays with him as he learns to carry it gracefully. As frequently as Cave seems to be exploring some elevated, fantasy realm in Ghosteen‘s lightest moments, what lingers are the hard truths and the hurt that never quite goes away. But Cave chose to let us into that world, into understanding his most vulnerable moments, and it’s a beautiful place to be, if one that’s hard to visit without shedding quite a few tears. It’s often said that music helps people feel less alone in the world. Perhaps with Ghosteen, the same can be said of Cave himself.

Label: Bad Seed Ltd.

Year: 2019

Similar Albums: Nick Cave & the Bad Seeds – Skeleton Tree

Nick Cave & the Bad Seeds – Skeleton Tree Sigur Rós – Agaetis Byrjun

Sigur Rós – Agaetis Byrjun Julia Holter – Aviary

Julia Holter – Aviary

When you buy something through our affiliate links, Treble receives a commission. All albums included are chosen by our editors and contributors.

Jeff Terich is the founder and editor of Treble. He's been writing about music for 20 years and has been published at American Songwriter, Bandcamp Daily, Reverb, Spin, Stereogum, uDiscoverMusic, VinylMePlease and some others that he's forgetting right now. He's still not tired of it.