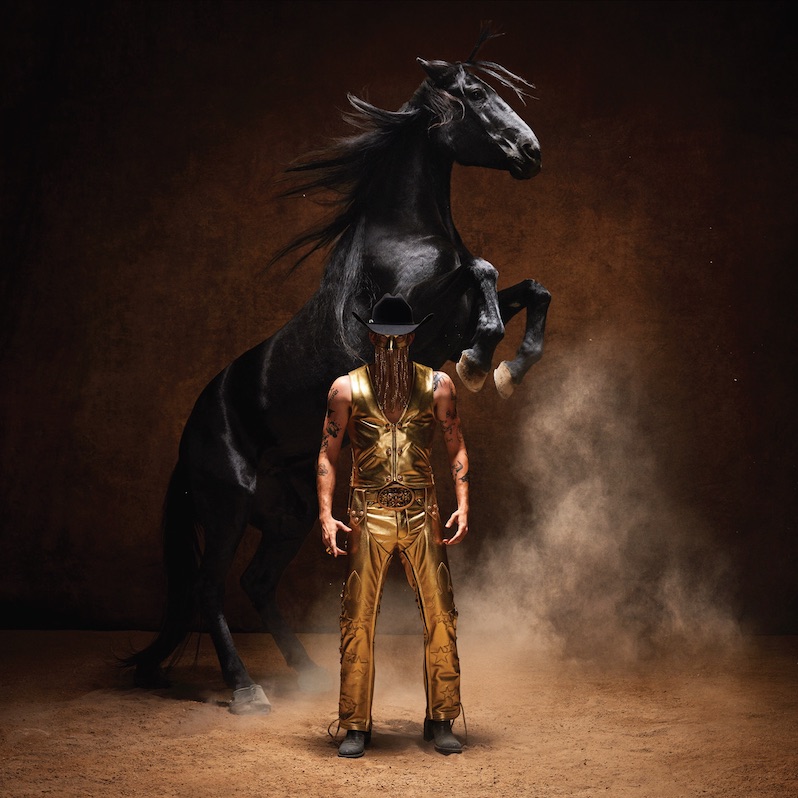

Orville Peck : Bronco

The first thing that may catch your ear on Bronco, the new record from Orville Peck, is how uncannily the opening track “Daytona Sand” seems to evoke “Neon Bible,” the title track from Arcade Fire’s second album. His sense of arrangement here doesn’t stray too far from that era of the once-venerated Canadian band, offering a blend of twee-affected Americana ruralism evoking more the era of star-spangled singing cowboys of country music than the blue-jeans-and-arena-crowds type. This isn’t the only track to live in that kind of sonic space, but it is also not the only space explored on Bronco, which feasts upon the great history of country music with great abandon, including all of its many manifestations, from the cosmic country ’70s to the days in the 2000s when you could play country to great critical acclaim so long as you called it folk instead (“indie folk” all the better for those crowds). What is it that makes this, much like Peck’s debut, resonate so much more deeply and successfully than other crass reconfigurations of country’s century-old body of music into something palatable to certain critic-friendly types? It’s simple: sincerity.

High in the skies above the dusty plains and southeastern American deltas caused by runoffs from the great Mississippi river there is a polestar, the same one for Orville as has long been cited by Nick Cave: Elvis Presley. Specifically evoked here is the weary, leather clad and open-hearted Elvis of the comeback years of the late ’60s, standing on a darkened stage before a Hawaii audience playing his god damn heart out for a comeback he just knew wasn’t going to come true. Elvis has a bit of a bad rap, not for unfair reasons, but a reputation that comes at least in part from misunderstanding; as far as misogyny is concerned, those claims are spot on, but regarding the racist framing of him as the king of rock ‘n’ roll, it was always a crown he struggled to shirk off either to credit his non-white bandmates or the worlds of music he drew from, only for a manager who tightly controlled the image of their million-dollar boy wonder to shut down those overtures to better market their product. By the later years, the weight of these things, sins he did and did not commit, crimes he could and could not make up for, wore heavily on the king, and the greatest survivor of the Tupelo tornado that killed so many was instead sweat-soaked and on the verge of tears as he begged an audience now given to the psychedelia and everything that would come after to come back to him.

This is, in an image, country music. Orville plays on Bronco with the same domains of country then, as it struggled to make sense of its history and the oncoming train of the future. There was exotica, Latin music, blues, folk, psychedelia, even a little Joao Gilberto. These reconfigurations would reemerge in the 2000s and 2010s as a kind of indie folk, if we remember, a post-alt country boom where these once-sincere sounds would instead be recaptured with toy instruments to evoke more the sense of hearing your grandparent’s records as a child. But Orville cuts clean past those crass kinds of approaches; when post-punk guitar shimmer comes through in his arrangements, it feels more like the closing of a great circle where the punks once influenced by country and early rock ‘n’ roll return their honed skills home. His voice here as on his debut is prairie-bound, the baying of the cowboy at the honeyed moon of Texas.

Everything said so far applies as much to Peck’s debut as to Bronco. So what’s different? Well for one, despite the decidedly moodier cover, this record is substantially more buoyant and joyful. There is still the lingering scent of tobacco drifting past the baking heat of low-hanging lights, but no longer are these songs exclusively for the country-twang goths hanging out in black cowboy boots hours past midnight. Even the sadness here is dripping with honey. This in turns allows the sadness in these songs to take on a more complex and mature texture, the way that emotions tend to self-complicate with time and age, every joyous moment streaked with the memory of people who can’t share it with us now and every moment of heartbreak bearing the quiet joy of still being alive. These are a mature set of songs, diving into the same emotional complexity that Nick Cave before him saw in Elvis and everything that came after. Years before country would crack, break, and fragment, with the psychedelic arrangers parting ways with the outlaws, the popstars, the mariachi bands and the Brazilian jazz cats, they would send a satellite out to space; Bronco returns to orbit 50 years later, an artifact of a potential alternate evolution of country music.

The most gratifying element of the emotional maturity Peck shows here is precisely in how it feels like an affirmation of, to many, the least desirable aspect of his work, that being his adoring and abiding love of country. He may have come from the world of punk and goth, but the goal of this project is clearly more to capture all the manifold angles and contours of the human heart and its life. Gothic music is an important aspect of this, the proper color for certain many elements, but is far from the only one necessary to capture what the world in adulthood looks and feels like in its confusion and mess. The clearly considered development present on Bronco compared to Pony, a consciousness present even in the relation-by-maturity of their names, bodes well for future development from Peck. Bronco doesn’t feel like an evolutionary dead end but a temporary stopping point on a fertile road; it feels safe to continue to place our faith in Peck’s creative capabilities. And with music for the gloom of the night and the honeyed sky of twilight, who knows what colors might come next? It’s good to feel excited.

Label: Columbia

Year: 2022

Similar Albums:

Langdon Hickman is listening to progressive rock and death metal. He currently resides in Virginia with his partner and their two pets.