Fight the power: The Top 50 protest songs

10. Bob Dylan – “Masters of War”

from The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan (1963; Columbia)

“I don’t sing songs which hope people will die,” Bob Dylan told the writer Nat Hentoff for the liner notes of The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan, “but I couldn’t help it in this one. The song is sort of striking out, a reaction to the last straw, a feeling of what can you do?” I admit the lyric “And I hope that you [the Masters of War] die” has always made me a little uncomfortable, but not as much as I seem to think it should. It’s probably because Dylan builds such a case against these monsters that by the time he gets to the end he’s bursting, and there’s not much else he can do except wish them death. That might not be the right feeling to have, but it’s an honest one and we can all relate. Of all Dylan’s “finger pointin’” songs, “Masters of War” is the pointiest. – Adam Ellsworth

9. Crosby Stills Nash and Young – “Ohio”

from So Far (1974; Atlantic)

We now take for granted how easy it is to respond to current events or Saturday Night Live episodes one might not be fond of. But 47 years ago, the speed at which Neil Young’s despairing lament “Ohio” got to market was remarkable. The National Guard killed four unarmed students at a Kent State Univeristy war protest on May 4, 1970. Two weeks later, after viewing a Life magazine pictorial about the tragedy, Young and CSN recorded “Ohio” live in a few takes at Los Angeles’ Record Plant. In June it was released as a single, hitting the Billboard Hot 100 around the same time as their meeker but still melancholy “Teach Your Children Well.”

“Ohio” consisted of only one verse and one bridge, both sung twice, suggesting there wasn’t too much in the way of verbiage that could sufficiently explain the heartbreak. The song’s second line tries, though; “We’re finally on our own” says a ton about both the idealism of young adulthood and the free-fall of man-made tragedy. Crosby’s choked shouts of “How many more? Why?” at the end were raw and ragged. Theoretically, “Ohio” could have consisted of just his words and still been more or less complete. – Paul Pearson

8. Black Sabbath – “War Pigs”

from Paranoid (1970; Vertigo)

“War Pigs” is a razor sharp production that conceptually was, at first, a simple flirtation and endorsement of the black arts, which through careful artistry evolved into a brilliant anti-war anthem. It’s certainly a song that’s so recognizable it’s no doubt entered the annals of music history. If there has ever been a time in which a state has forced its citizens to fight, “War Pigs” has presented an awful examination of the slave-and-master dynamics of a government at war. The track isn’t just important because of its lyrics, or it’s relatable nature. It’s lasted as long as it has because it absolutely fucking rips. Groove-laden refrains, outbursts of pure unadulterated metal riffs. Brilliant. – BR

7. Kendrick Lamar – “Alright”

from To Pimp a Butterfly (2015; Top Dawg/Aftermath/Interscope)

Kendrick Lamar’s To Pimp a Butterfly resonated so wide and far upon its 2015 release for a lot of reasons, among them its musical experimentation, its complex conceptual threads intertwining personal conflict with success and the Tupac mythos, and Lamar’s own unstoppable lyrical prowess. It also reflected a series of years in which institutionalized racism reached a tragic conclusion far too often. It’s not a protest album in the Public Enemy sense but its centerpiece, “Alright,” became an anthem for the Black Lives Matter movement in the months following its release. “Alright” isn’t just a song that reflects the black experience in the ‘10s, but a cumulative history of struggles toward the advancement of civil rights, a reminder of every hard-fought battle of the past and every still-to-be-fought battle ahead. “Wouldn’t you know, we been hurt before,” Lamar says, optimistic but by no means naive. “We gon’ be alright,” he reassures, assisted by a jubilant Pharrell Williams. Kendrick Lamar knows it can and will get worse before it gets better, but what “Alright” sacrifices in immediate joy it makes up for in warmth and solidarity. Maybe there’s still a long way to go, but we can get there if we go together. – JT

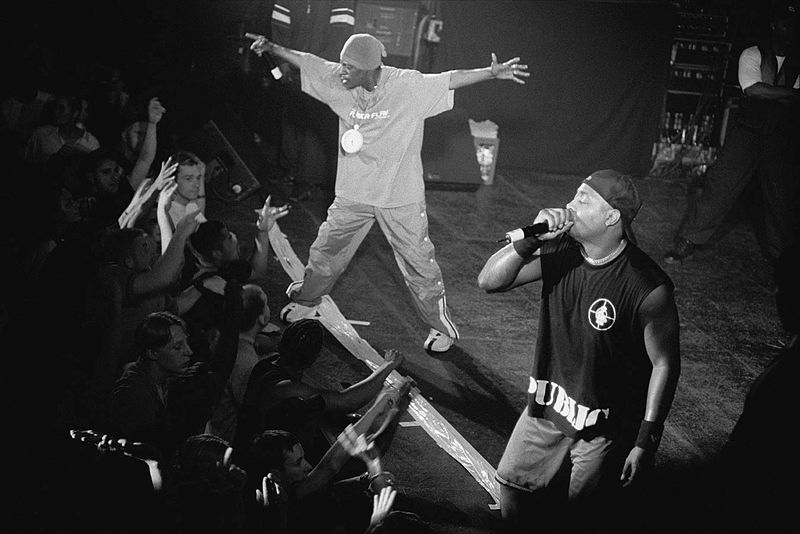

6. N.W.A. – “Fuck Tha Police”

from Straight Outta Compton (1988; Ruthless)

Compton, California was gang country. Police-developed maps of the city showed all its neighborhoods under gang control except for a strip of industrial buildings in the south. Compton and Los Angeles police began focusing attention on street gangs in the mid-1980s, stepping up detainment of men who fit the profiles they’d constructed. “A war on gangs, to me,” Ice Cube said in a panel for the N.W.A. biopic Straight Outta Compton, “is a politically correct word to say a war on anybody you think is a gang member. So the way we dressed and the way we looked and where we come from, you can mistake any kid for a gang member—any good kid.”

“Fuck tha Police” was Ice Cube and MC Ren’s response to the harassment, depicted in the film as a shakedown N.W.A. received while recording their album in Torrance. For those in the crosshairs, “Fuck tha Police” was another example of Chuck D’s trope about rap music being “the black CNN.” But suburban white America, still crotchety from Tipper Gore’s explicit-language crusade, flipped out over the revenge fantasy element of the song, conveniently ignoring the explanatory set-up Cube provided in verse one. It took the 1991 videotaped beating of Rodney King for them to realize N.W.A. weren’t making it up, and the LAPD’s Rampart scandal exposed corruption in some anti-gang units. By that point “Fuck tha Police” finally became accepted as a reflection of society, not a threat. Sadly, its endurance is partly due to the fact that it’s still entirely relevant. – Paul Pearson

5. U2 – “Sunday Bloody Sunday”

from War (1983; Island)

The militant march to U2’s anthem sets a tone better than most. The lyrics tell the tale of an ill-fated day in 1972 Derry, Ireland when British troops shot and killed protestors, a boiling point during the Troubles conflict in Northern Ireland—which only escalated further. A classic of the band’s post-punk era, it’s the sound of a defiant U2 that paired their socio-political outlook with an anthemic intensity to match. “How long must we sing this song?” Bono asks, addressing the violence in context—though it has endured as one of the band’s live-set staples for 30 years, so there’s that. This should be on any list of the 10 best U2 songs. – Wil Lewellyn

4. Sam Cooke – “A Change is Gonna Come”

from Ain’t That Good News (1964; RCA Victor)

The symphonic gravitas of Rene Hall’s string arrangements were a radical choice for a 1964 R&B number that was initially never intended for single release (and was initially pressed as a B-side to “Shake” when it did arrive on 7-inch). But it is the determination in Sam Cooke’s writing that an African American former gospel singer would not be silenced in his outrage, sense of injustice, and commitment to hope that elevates this beyond its 1964 setting. Fueled by an incident where he and his band were turned away from a whites-only hotel in Shreveport, Louisiana, and liberated by the metaphorical transgression of Bob Dylan’s “Blowin’ in the Wind,” Cooke set out to articulate his fury. The song became the defining civil rights anthem of the age, and despite Cooke’s untimely death later in the year, the strength he offered to others guaranteed that he was never absent from a march, protest or moment of history ever again. – Max Pilley

3. Gil Scott-Heron – “The Revolution Will Not Be Televised”

from Pieces of a Man (1971; Flying Dutchman)

The late Gil Scott-Heron was a born leader. A modern day visionary, he was responsible for pioneering black activist music and poetry through a lifelong struggle for justice. Following in Langston Hughes’ footsteps, Scott-Heron enrolled in Lincoln University in Pennsylvania, where he would combat a reactionary administration and kick start an art career through his brilliantly ambitious poetry, literature and music. He and longterm collaborator Brian Jackson would form Black & Blues while Scott-Heron was in the midst of writing his first published novel, The Vulture. Combining his passion for music and literature, Scott-Heron would begin to compose spoken word verse set to blues, soul and jazz, producing intelligent proto-rap numbers with penetrating political grit. Arguably his greatest (and most famous) work, “The Revolution Will Not Be Televised” is bone chilling, completely authentic and inarguably genius. Drafted during a newscast on recent demonstrations, “Revolution” meticulously captures the essence of reality juxtaposed to the falsity of advertisements presented on television—something we may subconsciously forget from time to time. January 20, 2017 marks the beginning of the revolution. And it’s most certainly live. – Patrick Pilch

2. Billie Holiday – “Strange Fruit”

(1939; Commodore)

One of the most haunting protest songs ever conceived comes, ironically enough, from places of relative privilege in the face of ghastly movements. What started off as “Bitter Fruit” was written and set to music in 1937 by poet and schoolteacher Abel Meeropol. A Jew and a Communist in the Bronx, Meeropol was likely not fully aware of the Nazi catastrophe coming to people like him—and millions of others—across the ocean in Germany. In 1939 his work found its way to the hands and ears of Billie Holiday who, despite the constant insults and professional limitations imposed by American racism of the day, had built a successful performance and recording schedule for herself. This included a then-new residency at the integrated New York club Café Society.

Meeropol’s piece was inspired by horrific photojournalism of lynchings in the American South, hanged and burned black men turned into ill-fitting foliage of the poplar and magnolia. “Southern trees bear a strange fruit/Blood on the leaves and blood at the root.” The pointed metaphor might have languished in union-meeting pamphlets had Holiday not found a sympathetic studio to record it, backed by a sad, spare arrangement from the Café Society band. She also planned smart stage direction at the club to feed years’ worth of rapt crowds a measure of despair and smoldering anger particularly inspired not just by her own injustices, but her father’s. It was a romantic composition that never romanticized its subject. Thanks to its place in her repertoire and a popular B-side on the single—”Strange Fruit” itself got no airplay—it became one of her best-selling songs, planting the seeds of its legacy as a quietly anthemic jazz standard. – Adam Blyweiss

1. Marvin Gaye – “What’s Going On”

from What’s Going On (1971; Tamla/Motown)

It’s ironic that the song we voted as the greatest protest song of all time is “What’s Going On,” but only in the context of its backstory. The Four Tops’ Renaldo “Obie” Benson, who wrote the song after witnessing the police brutality against anti-war protestors on “Bloody Thursday” in Berkeley, said that it wasn’t in fact a protest song despite his bandmates’ claims to the contrary. “It’s a love song, about love and understanding,” he said, eventually collaborating with Marvin Gaye, whose own goal was to release the very thing that Benson said “What’s Going On” wasn’t. It’s funny in that way, an interpretive statement that can be heard as either protest or peaceful plea, a veritable political pop Mona Lisa. Similarly, its title can be read as either question or statement—a demand to know what’s causing violence at home and in Vietnam, or a reading of the horrific state of the world in the Nixon era. “Mother, mother/There’s too many of you crying/Brother, brother, brother/There’s too many of you dying,” Gaye sings, nodding to his actual brother Frankie, a Vietnam veteran who partially inspired the song. In 1971, “What’s Going On” spoke to a senseless brutality that plagued the world. Play it now, however, and it’s a heartbreaker to hear just how little things have changed. – JT

GMO protest song:

Superweed – The GM Food Song

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VpCEdtWPQSI

no The Clash song? Really?

Hey there, one of the authors here, just saw this comment. The Clash were victims of vote-splitting: a bunch of their songs were nominated, and no clear favorite emerged at the end. Speaks to their consistency, I suppose. Maybe they should have been here, but I’m sure we’ll continue to give them their own spotlight[s] in the future.

I would have included the Special AKA’s “Free Nelson Mandela.”