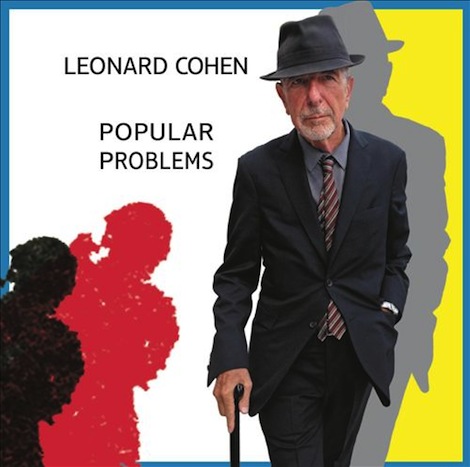

Leonard Cohen : Popular Problems

Leonard Cohen’s last couple of albums, including Popular Problems, have this visceral effect that’s hard to pin down. About the best way I could put it is they stop time. Cohen’s music has usually arrived with the most basic dressing it needed, but there’s something commanding about the simplicity and quietude of 2012’s Old Ideas and this one that it’s almost telepathic. It’s impossible to hear anything else around you when it’s playing.

I suppose it could be the honeyed gravitas Cohen’s voice has, especially lately; or maybe it’s the somewhat tired proposition that artists around his age (he turned 80 last Sunday) at least partially use their art to settle past emotional accounts. As much as I don’t want to use that war horse to explain Popular Problems, there’s just too much of it on the album to do otherwise. But Cohen’s not necessarily interested in reliving those memories so much as he grapples with their multiple interpretations.

Co-written with behind-the-scenes pop force Patrick Leonard, Popular Problems places Cohen’s voice in the role of inquisitive conscience. The spoils of victory and the remnants of loss aren’t really relevant anymore, and in each of this album’s nine songs Cohen tries to leave the scene with at least some takeaways. He doesn’t always get one. In “Almost Like The Blues,” Cohen relates to catastrophes (“There’s torture and there’s killing/And there’s all my bad reviews”) in an artist’s way, but can’t get past his mere act of observation. And in his detachment he finds that he’s almost absorbed awful inclinations almost by osmosis (“I have to die a little between each murderous thought/And when I’m finished thinking I have to die a lot”). The rest of the songs play with that balance and opposition in crisp, clean accord with his typical economy.

But if the character in “Almost Like The Blues” seems remote – which he is, which is why the song’s a great one – other voices on Popular Problems ring with an acidity that’s bracing and far-reaching. “Samson In New Orleans” shakes a fist at the suddenly malevolent, or even worse unconcerned, deity who let Hurricane Katrina decimate a jeweled city (“She was better than America”) and seemingly abandon its denizens over their lack of import to the complex: “We who cried for mercy/From the bottom of the pit/Was our prayer so damn unworthy that the Son rejected it?” All this plays over a dark and spare synthesizer hook and a mock prayer ceremony.

The tatters of war figures in “A Street” and “Nevermind,” where the cause for the conflict carries not one ounce of weight in the face of what tolls the survivor pays. “A Street” examines a relationship all but neutralized by destruction that leaves no possibility for comfort: “You always said we’re equal/So let me march with you/Just an extra in the sequel/To the old red white and blue.” “Nevermind” presents a whole load of conflicts and, maybe, contradictions. In clipped fragments the singer assesses his own role, though he doesn’t sound that sorry: “I had to leave/My life behind/I dug some graves/You’ll never find.” Then he stamps out even the intangibles that were left, like love (“The Great Indifference”), that now have no real value: “Names so deed/And names so true/They’re blood to me/They’re dust to you.”

The more personal songs are so simple and demystified they’re almost comic, but that probably means Cohen knows that if he’s apt to find peace it will be in private. “Did I Ever Love You” finds him questioning his own memory of a romantic arc in relative solemnity, before an uptempo country chorus drops in unexpectedly as his background singers echo back to him. The contemporary folk drifter “My Oh My” offers no more than three complete thoughts about a brief episode, which is fine because Cohen just wants to celebrate, or at very least commemorate, the moment.

“Born In Chains” – reportedly a song Cohen has been working on for decades – puts him square in the middle of the story of Exodus, reflecting not only on his Jewish heritage but the alterations he’s made to his beliefs over the course of a lifetime. The closer “You Got Me Singing” works on just about every imaginable level. As a tribute to a muse that’s persisted even as the external world has crumbled, you can’t avoid the implication that Cohen is making a prelude to his own departure: “You got me singing/Even though the world is gone/You got me thinking/I’d like to carry on.”

Cohen and Patrick Leonard maintain the same strategy of moody, uncomplicated music that supports the quiet imposition of his whispering voice, which has become one of contemporary music’s most unmistakable sounds. “Did I Ever Love You” flirts with playfulness and “Nevermind” builds on a dark funk bass and freestyle Middle Eastern singing, but elsewhere the supporting sounds are uncluttered beds of mood and very light pulses. “I always liked it slow,” Cohen sings in the opener “Slow,” before continuing with another collection of focused songs that stop time. You’ll only lose 36 minutes of your life, but you’ll get back a lot more.

Similar Albums:

Leonard Cohen – Old Ideas

Leonard Cohen – Old Ideas

The Velvet Underground – The Velvet Underground

The Velvet Underground – The Velvet Underground

John Cale – Shifty Adventures in Nookie Wood

John Cale – Shifty Adventures in Nookie Wood

Paul Pearson is a writer, journalist, and interviewer who has written for Treble since 2013. His music writing has also appeared in The Seattle Times, The Stranger, The Olympian, and MSN Music.