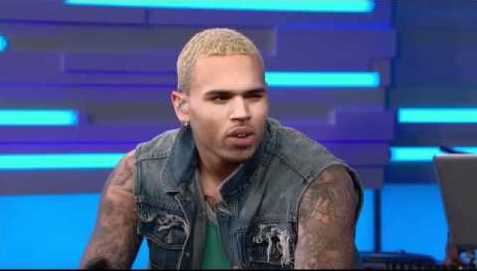

Chris Brown and the question of offstage behavior

I didn’t watch the Grammys this year. I couldn’t actually – in my house, there’s no cable or digital receiver, just Netflix and Hulu. But social networking made sure that none of the venerable industry award show’s narratives went untold, from the awkward acceptance speeches, to the strange programming choices, and whatever totally outrageous thing Nicki Minaj did. But not even a second year of indie rock nods (‘sup Bon Iver) seemed to overshadow the biggest story of the evening: Chris Brown won a Grammy.

This, on its face, might not seem like a big deal. A predictably conservative jury awarded an artist based on a reasonably successful album. But ever since the news broke that Brown brutally assaulted Rihanna in 2009, his music has been a distant second story to his offstage reputation. Domestic assault is a hard thing to forgive, and Brown’s increasingly hostile behavior certainly didn’t make it any easier for people to look past. And once the eventual police report came out, it painted an even more horrific scene, documenting Brown as not only engaging in a vile, reprehensible act of violence against a woman, but actually threatening death. Brown apologized after the news broke, and took a plea deal for a light sentence of five years of probation, six months of community labor and domestic violence counseling. And an emotional (but tacky) performance at the 2010 BET Awards revealed Brown in a kind of struggle with his own demons, attempting to show the world that he was wrestling with his own mistakes, but at least acknowledging them.

Cases like Brown’s aren’t necessarily unique, which is a sad statement in and of itself, and he’s far from alone in having to face down a scandal of his own doing. But this situation marks that rare occasion in which a performer, someone whose own art can act as a form of escape, shatters the illusion that many fans hold and emerges, not as a pop ideal, but as a fallible, flawed human being. Or, worse still, even a monster. When we listen to music (or watch a film or read a book), we tend not to think about what kind of people are making it, whether they’re of good character or ethics. And sometimes, we probably shouldn’t. Sometimes the art that’s the most rewarding is that which is most challenging to the listener, and can sometimes open up questions about ourselves we may never have sought to ask. But once we are faced with the idea of an artist, whose work we enjoy, revealing personal failures as a human being, those questions we inevitably end up asking ourselves – “Can I still enjoy the art?” “What does this say about me, as a consumer?” – become all the more uncomfortable.

Brown, it would seem, was initially met with a public willing to move on, and he’s been spared no shortage of second, third and fourth chances. As a society, we like a good story of redemption, of a fallen hero coming back from some time in the wilderness only to arrive a new person. Football fans were more than ready to welcome Michael Vick back after he served time for animal cruelty charges. And Brown, likewise, might have won over some public generosity, deserved or not, had he continued to take the right steps to earn them. But Brown has this nasty habit of squandering all of his second chances. In 2011, he appeared on “Good Morning America,” and flew into a fit of rage after answering some questions about Rihanna, tearing off his shirt, trashing his green room and smashing a window with a chair. And if that didn’t adequately alienate enough people, after his Grammy win, he tweeted the following: “HATE ALL U WANT BECUZ I GOT A GRAMMY Now! That’s the ultimate FUCK OFF!” Not long thereafter, his public relations and management team were in damage control mode, and in less than 24 hours scrubbed his entire Twitter feed, leaving only 11 messages on his account.

For fans of Chris Brown’s music, this is no doubt a frustrating series of events to watch unfold. For me, personally, Chris Brown’s music has never had much appeal, and given the severity of his crimes, I’d just as soon see him disappear from pop music. But for fans, critics or observers on the sidelines, it only serves to dredge up those uncomfortable questions: What kind of behavior are we willing to tolerate from celebrities, entertainers and artists we admire?

Truth Hits Everybody

Every consumer, listener or viewer will, inevitably, reach the point in his or her life at which an artist will do something scandalous or appalling, and that person will wrestle with perception of that artist’s art in the aftermath of those actions. Maybe it’s easy for me to reach a quick conclusion with someone like Brown, whose music I find inconsequential and whose behavior I find utterly reprehensible. But that doesn’t mean I’ve never felt some sort of personal conflict with a piece of art created by someone who has done something to tarnish his or her goodwill, and just about anyone reading this piece will likely have been in the position of re-evaluating an artist’s work in light of personal indiscretions.

It’s an unfortunate truth that a large number of musicians and actors have been involved in some form of domestic abuse, from James Brown to Ike Turner, whose own musical career is permanently marked with an asterisk because of his abuse against Tina Turner. Nick Oliveri, formerly of Queens of the Stone Age and Kyuss, likewise, has been investigated for domestic abuse charges a couple times, the most recent of which actually ended with a SWAT team standoff, which is some indication of just how out of hand the situation became.

Of course, none of these holds a candle to Mel Gibson, whose own audiotaped record of abuse, racism, misogyny and outright violent temperament put him in a special category all his own. And Gibson, much like Brown, seems to dig himself deeper into a pit of public shame the longer he tries to rebuild his career. Yet, if I’m to be perfectly honest with myself, I’d probably still enjoy Mad Max or Lethal Weapon if I were to watch them today. And likewise, while Nick Oliveri has sort of gone off the deep end, I still enjoy the Queens of the Stone Age albums on which he performs. Maybe it’s a poor justification, but I don’t really see how Josh Homme or Mark Lanegan should lose my support because one of their former collaborators did something unsavory. The same goes for Judas Priest, whose former drummer Dave Holland was convicted of attempted rape of a minor. Appalling, sure, but I also can’t fault Rob Halford, Glenn Tipton or K.K. Downing for something that Holland did.

And that leads to another set of questions: Where do we, as listeners, as fans, draw the line? And, perhaps just as importantly, should we?

The Harder They Come

There’s something to be said for being able to separate art from artist, and it becomes a lot easier the less you actually know about a performer. There are certainly cases in which sensationalism of particular events sometimes overshadows the art. As a fan of black metal, I was well aware of the church burnings in Norway in the ’90s, and the murder of Euronymous at the hand of Varg Vikernes of Burzum, who has since served his prison sentence and re-entered society to continue recording as Burzum and occasionally post an anti-Semitic rant on his website. Vikernes is an extreme example, however, and while I can make my peace with the fact that some bands try to out-evil each other, an actual murderer and vessel for race-oriented hatred is essentially a non-starter for me. I’ve heard plenty of convincing arguments for being able to enjoy Burzum’s music without actually supporting what Varg believes in, particularly because it doesn’t play any part in the music he makes. But I also know that the majority of black metal bands don’t harbor the same beliefs, so I’d much rather just move on and lend those artists my support.

The bigger the artist, and the more notorious the actions, the harder that separation becomes, particularly when critics and defenders seem to maintain equal volume. In the last 20 years, no artist has been as divisive in how he’s been perceived offstage as Michael Jackson. In the ’90s, Jackson was on the receiving end of some child sexual abuse charges, some of which went away quietly, and some of which were ultimately defeated in court. And given Jackson’s eccentric behavior, for many this wasn’t a difficult thing to believe. It’s become the stuff of urban legend and tasteless jokes, not to mention endless speculation. It was never actually proven, and he was acquitted of all charges. But by that point, most people had already made up their mind, and while Jackson remained a celebrated artist (the “King of Pop”), to some his reputation was forever tainted.

With someone like Michael Jackson, however, no matter how grotesque his appearance became, or how strange he behaved in later years, without actually knowing for certain he did anything wrong, I have trouble allowing myself to jump to that conclusion. And even if I could, when I hear Off the Wall, I don’t hear a troubled soul so much as a talented singer in his younger, more hopeful days. For many listeners, and I find myself behind this perception from time to time, Jackson was such a legendary and mythical figure that he didn’t often translate as a vulnerable or imperfect human being, and whatever the real Michael was like, his art is how we identify him.

The situation grows more complicated when you apply it to a figure like Roman Polanski, who was arrested in 1977 for sexual abuse of a 13-year-old girl, and subsequently fled the country to escape sentencing. In this case, there’s no speculation. It happened; Polanski actually accepted a plea bargain before deciding to leave the country. And, understandably, this is beyond the pale, reason enough not to support the man’s work. Still, his work remains celebrated, he’s won three Oscars since then, and he never actually served any prison time. And once again, though I hold personal conflict over it, I still enjoy his films, and given his background, having survived the Holocaust and suffering the trauma of losing his pregnant wife and unborn child in a brutal murder, it gets even more complicated. It’s not a justification, but it’s definitely complicated.

I could continue giving examples of artists whose own actions have landed them in public relations purgatory, and who in turn may have very well turned off those who once supported them. And those very same examples will no doubt have their share of staunch defenders. As consumers, we’re prone to follow a gut reaction, and whether that causes us to distance ourselves from the artist or merely be unaffected, neither reaction is necessarily right or wrong. It’s an individual reflex. Speaking strictly for myself, most of the time art and the artist can be separated, but there are definitely exceptions. And no matter how little investment I have in certain personalities, I can’t help but feel comforted by the fact that some of those artists who I admire are, in fact, decent people.

But for an artist like Chris Brown, whose career longevity may very well depend on perception of who he is as a person, is only revealing his own immaturity when he expects redemption to happen overnight. Whether he likes it or not, he is not defined by his music anymore, but by his crime, and broken windows, Twitter rants and teal bow ties aren’t going to change that. In time, Brown may find himself among more welcoming company, but that’s largely up to him. Some will still enjoy his music, and some will refuse to acknowledge it, but for the time being, Brown shouldn’t be surprised if people are reluctant to forgive. He hasn’t given them any reason to.

Jeff Terich is the founder and editor of Treble. He's been writing about music for 20 years and has been published at American Songwriter, Bandcamp Daily, Reverb, Spin, Stereogum, uDiscoverMusic, VinylMePlease and some others that he's forgetting right now. He's still not tired of it.