Hold On To Your Genre : Dub

For a brief period of time, in the 1970s and ’80s, Jamaican music crashed the American and British mainstream. For this, we can thank Bob Marley, an artist whose iconic status made him an equivalent Bob Dylan, John Lennon or Elvis Presley within the annals of reggae music. Yet the influence and success of Marley’s music, outside of his own country, was something of an anomaly for reggae music. He certainly wasn’t the only artist to have entered the public consciousness outside of the birthplace of reggae — Peter Tosh, Jimmy Cliff and Toots & the Maytals (not to mention third-wave ska) each established themselves on a global scale, if not quite to the level of Marley.

Yet despite the efforts of massive rock acts like The Police, The Rolling Stones and Eric Clapton drawing greater attention to roots reggae, the vast expanse of reggae music generally went unnoticed outside of its country of origin. That’s not necessarily surprising — the success rate of cross-cultural breakthroughs in popular music tends to be low, and frequently relegated to novelty status. Yet when considering the influence of dub, a reggae subgenre more or less responsible for inventing the remix, heavily influencing hip-hop, and forming a basis for ambient, jungle/drum & bass and dubstep, it’s both wonder and shame it’s remained primarily an underground concern.

So let’s get to the important question: What is dub? Named for the simple act of “dubbing” over recorded sound. Initially taking existing rhythm tracks and applying other layers of instrumentation or vocals (sometimes “toasting” as in dancehall, which was a precursor to rapping as we know it today), dub began very literally as a genre of remixes. Or, if you prefer, “versions.” But from that blueprint, dub expanded into an even wider range of stylistic outgrowth and evolution.

In dub’s earliest incarnations in Jamaica, genre architects like Lee “Scratch” Perry and King Tubby were early innovators of production in dub, working with existing tracks by picking the vocals and instrumentals apart and crafting new Frankenstein’s monsters out of once-familiar tunes. But soon after some of the dub experiments in clubs began to catch on, artists began to compose entire albums of original material mixed in a dub style, starting with reggae rhythms and crafting a new sonic spectrum on top of them. Errol Thompson produced what is commonly considered the first true dub album, Derrick Hariott’s The Undertaker. A year later Keith Hudson released Pick A Dub, which deepened consciousness of dub, while Tubby, The Upsetters, Augustus Pablo and Prince Far I all eventually built up pretty sizable catalogs of dubplates and albums.

By the late ’70s, dub was still fairly obscure on a commercial scale (outside of Jamaica and, to a certain extent, the UK), but many artists in punk, post-punk and new wave began to incorporate elements of dub in their music, from its rhythms and production techniques to the prevalence of melodica, which was popularized by Augustus Pablo. Artists like The Police, The Clash, UB40, The Slits, Grace Jones (herself Jamaican born) and numerous others began to fuse pop and punk music with dub flourishes. And that eventually led down the path to new burgeoning techniques in electronic music, with acts like The Orb, Leftfield, Goldie and Massive Attack taking the roots of dub and molding them into new, innovative shapes.

The roots and influence of dub cover a pretty massive range, and it’s a fairly daunting task to try to cover it all, but we’re breaking it up into three separate sections, covering different eras, movements and evolutionary periods. Now, to start the dub riddims.

Also, listen along to our dub essentials and dub-influenced favorites in this Spotify playlist.

Dub from the Roots

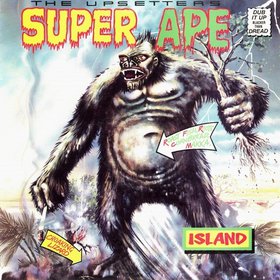

The Upsetters – Super Ape

The Upsetters – Super Ape

(1976; Island)

Lee “Scratch” Perry remains the yardstick against which all other dub producers are measured, even as his work has gotten more fucked-up across the passage of five decades. In his later sounds many observers still find genius, but Super Ape is tight on so many levels. On it he helps The Upsetters reconfigure others’ instrumentals, introduces strong vocal harmonies in empty spaces, and strips away layers of performance in other spots. The collective ends up hitting perfect notes of mystery with the typical (dub’s signature echoes, most haunting in the middle of this album) and the atypical (listen for the pastoral recorder played during the title track). Thin on message but thick on atmosphere, there’s enough formally structured lyricism above and beyond the wobble to consider Super Ape a straight-up reggae release, one of the few to hold its own against Bob Marley’s mid-1970s juggernaut. – AB

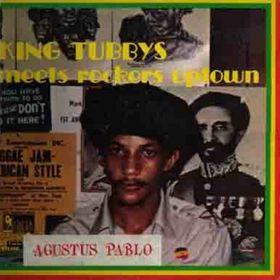

Augustus Pablo – King Tubbys Meets Rockers Uptown

Augustus Pablo – King Tubbys Meets Rockers Uptown

(1976; Clocktower)

Released in close proximity to Super Ape, this is much more pure dub that should be subtitled “the keyboard player meets the mixing engineer.” Rockers Uptown featured almost wholesale replacement of vocals with Pablo’s organ and melodica lines, weaving among choppy island guitars and the echoing peaks and valleys of King Tubby’s production. It’s also a showcase for drum and bass — no, not the hyperactive 1990s electronica, but where one-drop innovator Carlton Barrett (one of Bob Marley’s Wailers) and Robbie Shakespeare (later of Sly & Robbie) made musical curiosity and playfulness manifest. This is a true landmark in the genre, flexible and influential, with hints suggesting so many different rhythmic musics in later decades from DJ Shadow’s plunderphonics to Daptone Records’ funk revival. – AB

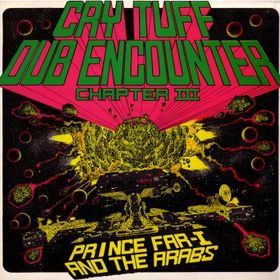

Prince Far I – Cry Tuff Dub Encounter Chapter III

Prince Far I – Cry Tuff Dub Encounter Chapter III

(1980; Daddy Kool)

Prince Far I’s first album, Cry Tuff Dub Encounter Chapter I, is credited to Far I (born Michael James Williams), but it’s a collaborative effort on the whole, a tradition that carried through to later editions of the CTDE series. The third is one of the most interesting releases in his catalog, finding Prince Far I at a creative high point as he crafts psychedelic dub textures with contributions from English musicians like David Toop and Steve Beresford, as well as Slits frontwoman Ari Up. It’s pretty powerful from the get-go, with Far I lending his commanding, almost preacher-like vocals to the booming opener “Plant Up.” The album eases up from there a little, traversing through several tracks of laid-back instrumental dub, but it gets more psychedelic and disorienting on side two, exploring some lengthier ambient terrain on “Homeward Bound” and booming depths on “Low Gravity,” before closing with an anti-Nuclear War sermon on album ender “Mansion of Invention.” That Cold War terror is reflected in the amazing album art, which was unfortunately swapped out on reissued editions. – JT

Next: Off the Beaten Track: Dub meets post-punk and industrial