I have always known Black Sabbath, even before I realized I did. “Iron Man” was in regular rotation in my high school pep band charts, and Cake’s cover of “War Pigs” popped up frequently in my dad’s well-used CD collection. It wasn’t until I miraculously stumbled across their legendary 1970 live in Paris video that I really started digging. One of my first ever pieces of music writing was a cringey Tumblr post about the advent of headbanging. At that point I was an overeager suburban core-kid, seeking the heaviest breakdowns at any cost, and I thought I knew all about heavy music. But Black Sabbath cut right through the downtuned noise that filled my iPod, bridging the distance between the progressive dad rock that I hadn’t yet come around to and that so-called metal of my youth. And it blew my teenage mind.

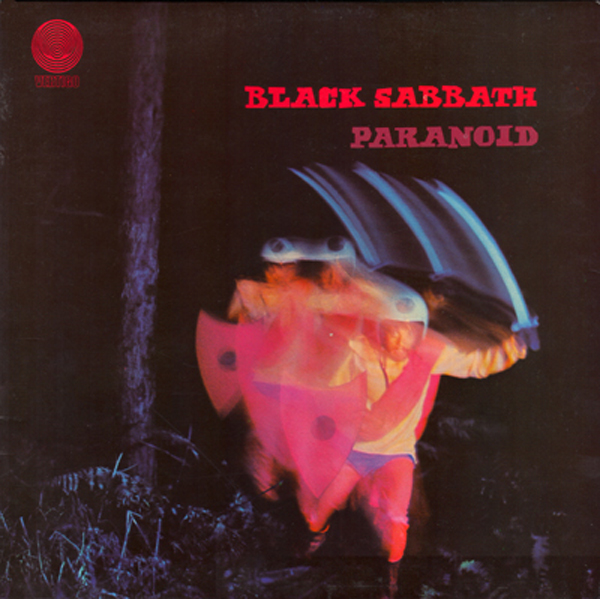

So it was then, years after experiencing my first mosh pit, that I found the same gateway to metal as many before me, a virtually universal experience that guarantees Black Sabbath a spot on the Treble 100. But why Paranoid? Black Sabbath’s self-titled debut takes the spot on our essential doom metal and top psychedelic album lists (not to mention the length our editor has written about that opening riff alone), and our pick for Sabbath’s contribution to essential stoner rock is Master of Reality. All three place on our list of Top 100 Metal Albums—but it’s Paranoid that takes the top spot there. Not everybody has to appreciate Paranoid as the foundational text of a genre, but anybody can and should hear it as the provocatively kick-ass record that it is.

In today’s terms, Black Sabbath looks a lot more like a demo than a debut, recorded nearly live in a whirlwind 48 hours just five months after their first ever show. In that context, it’s less surprising to see their follow up, Paranoid, recorded just four months later. But how much the group improved in that time does remain astonishing. Their debut record shocked the world with its sharp divergence from the bluesy rock and roll of the era. But at the same time, Black Sabbath simply dealt in extremes, roughly alternating that divergently dark sound with a groove clearly taken from the mainstream playbook. Paranoid proved that the new genre could have it both ways. The perfect model of heavy metal both subverts and succeeds the prevailing commercial tendencies of rock and roll, gutting out its shell of debauchery and filling it with the substance of a raw emotional critique of life.

Black Sabbath’s mastery of that gray area between hedonism and humanism speaks to the enduring legacy of Paranoid. Those are the roots of heavy metal as a culture, not just a genre.

Looking back on it as a far-reaching cultural force, Paranoid also reflects the ways in which other art has been influenced by heavy metal and subsequently incorporated various elements. If Paranoid doesn’t sound as heavy as we might expect, 50-plus years on, that’s because Black Sabbath skewed the scale of mainstream culture toward that heaviness.

Paranoid is the origin point for not just heavy metal music as we know it, but also for the mainstream misinterpretation of metal. Rolling Stone’s review, for example, was mostly just a bizarre mischaracterization of Satanism, but it’s a striking example of the way Black Sabbath was both demonized and disparaged. The critical rejection of Paranoid foreshadowed the dominant media response to heavy music in perpetuity: strategic decontextualization of provocatively incisive lyrical themes in an effort to undermine the potential of music to inspire critical thinking. This album was not only my gateway to appreciating metal but also to my deep inclination towards criticality. Reading more and more about how Black Sabbath was received and talked about made me the skeptical and suspicious person that I am. Why didn’t they want kids my age to listen to it when it came out?

The stakes may seem relatively low, if we’re only talking about the censorship of a musical subgenre. But we’re really talking about the media landscape established by the Second Red Scare of the ’50s and ’60s. The occult accusations against Black Sabbath, alongside many other controversial artists, marked the rise of the Moral Majority in the ’70s, a wave of true paranoia that turned countless lives upside down. Ironically, a closer read of the lyrics reveals a literalist Christianity, possibly even an internal critique of the church from a faithful perspective. In “War Pigs” Satan may be “laughing, spreading his wings,” but that’s only because God rightly calls down judgment on the sinful worms of the ruling class. To dismiss the nuance at play there is plainly ignorant.

Much of the rest of the album is otherwise intensely critical. Most lines in “War Pigs,” even taken out of context, could be sizzle phrases pulled from any number of iconic anti-war speeches. Meanwhile, Geezer Butler has said of writing “Paranoid” that he “didn’t know the difference between depression and paranoia,” blurring the boundary between different facets of disillusionment. Superficially, both “Electric Funeral” and “Hand of Doom” could be misconstrued as glorifying or reveling in the horrors of nuclear armageddon and drug abuse respectively, but it doesn’t take a much closer read to reveal the exact opposite.

Ultimately, the politics and philosophy of Black Sabbath’s music are not so cerebral anyway. The original quartet were rightfully ascribed to their scrappy, working class origins, but (at least at the time) wrongfully dismissed as such. These twenty-somethings from post-industrial Birmingham didn’t need a complex theory to understand that their hometown was broken in ways that reflected the crimes of an empire in decline. By the same token, any listener needn’t be well versed in that history or read very closely to be moved by the critical currents running through Paranoid.

Black Sabbath did not make the world an evil place. Paranoid didn’t make us feel unnecessarily bad about it either. In fact, Butler’s confusion of paranoia and depression is a perfectly appropriate way to feel about the state of society. But that’s not a good look for the ruling class. So instead, it’s not your soul sucking job or the depressing design of suburbs or the endless wars that are making you feel hopeless, it’s that devil music. This all probably sounds a little conspiratorial, and admittedly the connections are thin. Maybe I’m just paranoid.

Treble is supported by its patrons. Become a member of our Patreon, get access to subscriber benefits, and help an independent media outlet continue delivering articles like these.

That linked Rolling Stone review is clearly a mislabeled review of a Black Widow album (I know this because it identifies the singer as Kip Treavor (sic), who was the singer for Black Widow). Not that your points are invalid by any means, but that review wasn’t talking about Black Sabbath.