Counter-Culture: The Top 100 Songs of the ’60s

The Beatles’ Revolver just celebrated its 50th anniversary. A few months before that, Pet Sounds turned 50, and Beach Boys songwriter Brian Wilson toured the album to mark the occasion. For many of us, these albums are not just part of the canon but the actual DNA of the music we listen to. Sometimes we take them for granted, but they shaped so much of the music that’s made even 50 years later. And at the time, they were radical statements—rebellious affronts to more conservative pop norms, even those of the bands that recorded them.

Most of Treble’s writers—actually, all of them—weren’t alive in the 1960s. The lens through which we view the decade is tinted by the last five decades. But as we’re in the midst of a turbulent time in U.S. history, fraught with violence, ongoing movements to advance civil rights, and the rise of a controversial and possibly dangerous right wing presidential candidate, it’s hard not to be drawn back to the culture of the 1960s and see parallels. More accurately, parallels with the counter-culture. In the 1960s, the youth turned against mainstream culture, embracing political protests and mind-expanding drugs, defying authority and pushing artistic limits. In many ways, the ’60s created what we now call “alternative” culture. And with these parallels and anniversaries fresh in our minds, we sought to document the musical highlights of the era.

To simply make a list of the best songs of the ’60s would involve combing through countless Beatles, Dylan and Stones songs, and that’s been done enough times that we didn’t really see the point. But so many radical things were happening in music that we wanted to dig deeper. So we present the best songs of the ’60s through the filter of counter-culture: Garage rock, psychedelia, free jazz, proto-metal, noise, minimalism—the list goes on. No artist appears on the list twice (we set a limit), in order to allow us to cover as much ground as possible. The ’60s is where pop music got really weird, and we hope you enjoy our journey through its highlights.

Photo by James M. Shelley, Creative Commons [CC BY-SA 4.0]

100. Eric Dolphy – “Hat and Beard”

100. Eric Dolphy – “Hat and Beard”

from Out to Lunch! (1964; Blue Note)

You can’t call Eric Dolphy’s “Hat and Beard,” the too-cool-for-the-real-world opening track of 1964’s Out to Lunch!, free jazz. It’s wild, it’s rambunctious, rebellious and rowdy, but not totally free. A just-turned-18 Tony Williams holds down a solid, if chameleonic beat while the rest of the ensemble goes Pollock on an avant garde groove. Dolphy blows a loopy solo on a bass clarinet. Freddie Hubbard goes dizzy on a manic trumpet solo. And Bobby Hutcherson seems to be in a sparring match with Williams, beating his vibraphone senseless until the bars damn near come off the instrument. No, this isn’t free, but whatever binds it is a mysterious force that only this ragtag band of iconoclasts could possibly understand. Out to lunch, indeed. – JT

99. Cecil Taylor – “Enter, Evening (Soft Line Structure)”

99. Cecil Taylor – “Enter, Evening (Soft Line Structure)”

from Unit Structures (1966; Blue Note)

“Free jazz” evokes chaos. It signifies musical parts in opposition to one another, a tangled thread of soloists all tugging and tussling with each other in an orgy of noise and pure, uninterrupted expression. But to say that John Coltrane’s “Ascension” sounds anything like Peter Brotzmann’s “Machine Gun,” however, would be not only wrong, but suggests a misunderstanding of that very freedom. In the case of “Enter, Evening (Soft Line Structure)”, the standout from Cecil Taylor’s beautifully intense Unit Structures, it means the freedom to be graceful and restrained. It’s almost an ambient piece, mischievous lines of piano and haunted clarinet squeals chase each other’s tails in a field of stark, percussive rumblings. Where Coltrane’s unencumbered expressions were spiritual in nature, and Brotzmann’s aggressive, Cecil Taylor’s creation feels more like modern classical than jazz, compositional and logical at its core, and desperately yearning to tear up the pages as it goes along. – JT

98. Nico – “Facing the Wind”

98. Nico – “Facing the Wind”

from The Marble Index (1968; Elektra)

A timpani splats off beat, creepy-crawly sounds fornicate along the walls, keys skitter trapped in a chord like veins in a fistula and they’re all dragged into the bobby-siren of a droning harmonium. These are the sounds of a world Nico is emotionally abstracted from but still indicted by. She sings she is “spinning on [her] Name, in the rain,” with a voice modified through a Leslie speaker detaching it from her presence. Nico is separated into two reliant distinctions: a woman who feels herself being eaten by fame and its (dis)representative images of her and the machinated voice she is surrogated into. She knows that music may expend emotional morasses and vaporize her momentarily from the world, but in the end it, too, waters the rain that impinges upon her. Ultimately, she presages the break from Warhol’s “nothing is something” glamorization of vacuity into the seventies “nothing is better than something” denigration. – BJ

97. Merle Haggard – “Mama Tried”

97. Merle Haggard – “Mama Tried”

from Mama Tried (1968; Capitol)

Not many in the outlaw country movement carried the authenticity of Merle Haggard, and that’s no lofty plaudit. Raised by his widowed, working mother from the age of eight onward, Hag kept finding new and varied ways to get into illegal trouble throughout the first 23 years of his life, finally landing in San Quentin, and changing his basic game plan after his 1960 release to go after a music career. Hag’s semi-autobiographical single “Mama Tried” may have been a day late and dollar short as an apology, but its economical description of rootlessness, loss and resignation is as cold and convincing as outlaw country ever got. – PP

96. Wailers – “Simmer Down”

96. Wailers – “Simmer Down”

from The Wailing Wailers (1965; Studio One)

Long before Bob Marley became the international face of roots reggae, and a superstar to boot, his group the Wailers made their debut with a catchy ska tune about growing violence in Kingston, Jamaica. This socially conscious message would become a key part of Marley’s oeuvre, with a body of work to come in the 1970s that would reflect the escalating conflicts in his home country and a desperate cry for peace. Here, however, that social consciousness is masked in a catchy and uptempo ska arrangement provided by The Skatalites. It’s a song so breezy and fun, you almost don’t notice the commentary. – JT

95. Blue Cheer – “Summertime Blues”

95. Blue Cheer – “Summertime Blues”

from Vincebus Eruptum (1968; Philips)

Named after a strain of acid that was floating around their neighborhood in the hippie haven of San Francisco, Blue Cheer was a middle finger to the flower children. The rumble kicked up in the distorted bassline driving their cover of the Eddie Cochran classic was heavier than anything even Hendrix could muster, and the drums pounded harder than what either Ginger Baker or Keith Moon had done before them. This power trio, managed by a member of the Hell’s Angels, influenced countless stoner rock bands on up to the present with their booming pre-metal attack. Even bands like Rush, who cite Blue Cheer as an influence, have covered the song—or covered the cover, more accurately. – WL

94. Bonzo Dog Band – “Death Cab for Cutie”

94. Bonzo Dog Band – “Death Cab for Cutie”

from Gorilla (1967; Liberty)

The Bonzo Dog Band, or Bonzo Dog Doo-Dah Band as they often called themselves, were sort of a British answer to the absurdism of Frank Zappa’s Mothers of Invention. The humor in their songs was sometimes dark, sometimes over the top (one song introduces the band, featuring Adolf Hitler on vibraphone, for instance) and frequently satirical toward other popular artists and styles. Like “Death Cab for Cutie,” a send-up of vintage Elvis via J.G. Ballard that ends up with the title character in a fatal car crash. It’s fairly twisted humor delivered in a silly package, with a title that later gave a band of indie rock hitmakers their name. – JT

93. The Seeds – “Pushin’ Too Hard”

93. The Seeds – “Pushin’ Too Hard”

from The Seeds (1966; GNP Crescendo)

Although not super well-known in most music circles, The Seeds are considered to be one of the most influential proto-punk bands and one of the early pioneers of garage-rock (along with contemporaries The Electric Prunes, who performed a tribute concert for deceased vocalist Sky Saxon in 2009, along with Love and The Smashing Pumpkins). Those styles are all over the band’s first two records, The Seeds and A Web of Sound, but “Pushin’ Too Hard” is especially anthemic. Lines such as “All I want to do is live my life and be free” are telling, and more than a bit indicative of Sky Saxon’s life post-Seeds, but charming. Charming and juvenile: isn’t that the whole garage-rock ethos, anyway? Still, “Pushin’ Too Hard” predates the dissonant, acid-fueled vibes of The Velvet Underground by a couple years. During one of the band’s performances of the song—captured on the live album, Raw and Alive, the band’s last great record—Saxon introduces the track with a dedication “to society and the world, because it still has a message.” Indeed, the message is clear. Drop acid, fuck, make some rock n’ roll, and die. Legacies are overrated. – BB

92. Al Wilson – “The Snake”

92. Al Wilson – “The Snake”

(1968; Bell)

The Northern Soul scene in England in the late ’60s and early ’70s is one of the strangest phenomena in pop music’s history. Groups of working class men and women would gather in old, worn-out nightclubs in industrial towns in Lancashire, and dance the night away to extremely obscure import 7-inch American R&B singles. The rare few British record collectors who made the journey across the Atlantic returned as heroes, with as many crates of vinyl as immigration would allow.

One of the most classic of the Northern Soul rare records was Al Wilson’s “The Snake,” which had originally been issued on Bell Records in 1968. Fast forward to August 1975, and the single narrowly missed out on the UK Top 40 after it was reissued due to popular demand from the Northern Soul fanatics. The only stranger twist that could have visited the history of the track arrived this year when Donald Trump read lyrics from the song when discussing the Syrian refugee crisis at a rally in January. What a world. – MP

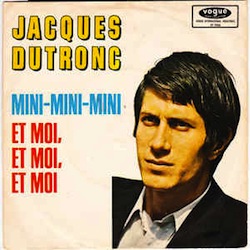

91. Jacques Dutronc – “Et moi, et moi, et moi”

91. Jacques Dutronc – “Et moi, et moi, et moi”

from Jacques Dutronc (1966; Vogue)

For a debut single, “Et Moi Et Moi Et Moi” proved Dutronc to be a hipster with confidence. With a head-bopping tempo and posh chords, the French singer-songwriter exuded the carefree attitude that the ’60s nurtured so well. Beneath the lax feel of the tune, though, lay a deep-seated rivalry. Dutronc’s debut was the result of contention between Christian Fechner and Jacques Wolfsohn, the artistic directors at Disques Vogue. At first, Wolfsohn asked Dutronc to work on the song for a rival act, known as Benjamin. Wolfsohn was unhappy with Benjamin’s rendition, so he requested that Dutronc’s former bandmate Hadi Kalafate record the vocals. Still unhappy, Wolfsohn simply had Dutronc record and release the track… Third time’s the charm. – VC

Did I miss it or is “Sympathy for the Devil”, “Paint it Black”, or “Mother’s Little Helper” not on this list? No Stones?

Not a single Stones song, hahahahahaha