Bonus Tracks: 10 More Essential Albums of the ’70s

It’s week three of Bonus Tracks month, and in this installment we’re looking back at what we missed during an entire decade. When we ran our list of the Top 150 Albums of the ’70s, we sought to cover as much ground as possible, from the electronic innovations in Germany, to the psychedelic jazz in Ethiopia, the pioneering Afrobeat sound in Nigeria, roots reggae in Jamaica, heavy metal being born in the UK, and punk rockers and singer/songwriters pretty much everywhere else. We did, however, overlook some great records, ones that sometimes coast just beneath visibility in the canon, and some that seem like pesky oversights. That said, given how much changed in music in the 1970s, we could keep this going for another 100. Here’s 10 more essential albums of the ’70s, just to show a glimpse of how much more amazing music there is to highlight.

David Crosby – If I Could Only Remember My Name

Five years before David Bowie released Station to Station, David Crosby produced If I Could Only Remember My Name. They couldn’t sound less alike, but both albums have basically the same premise: A guy named David gets so fucked up he starts to lose all sense of who he is. If I Could Only Remember My Name’s guest list is practically overflowing with brilliance—four Grateful Dead members on “Cowboy Movie,” Graham Nash and Neil Young on “Music Is Love”, all of them and more on “What Are Their Names.” It’s only in the moments when Crosby sounds alone that the high wears off and the pain at the heart of the album emerges, briefly flickering into clarity before vanishing once more. – Jacob Nierenberg

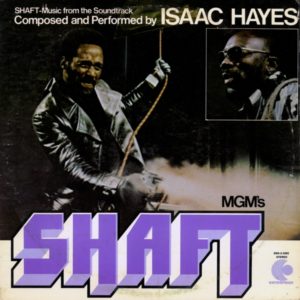

Isaac Hayes – Shaft

The blaxploitation films of the 1970s were only as good as their soundtracks, and Shaft—whether you’re talking about the movie or the album—was one of the finest documents of its era. The main theme, with its scratching wah-wah guitars and tooting flutes, remains a masterpiece, but there’s plenty more to Isaac Hayes’ score. It’s been nearly 50 years and we can still dig the jazzy guitars on “Cafe Regio’s,” the socially conscious “Soulsville,” the 19-and-a-half-minute funk monolith “Do Your Thing” and everything in between. You’ll never be half the bad mother-shut-your-mouth that Shaft is, but Shaft is the album to throw on, without a doubt, when there’s danger all about. – Jacob Nierenberg

Keith Hudson – Flesh of My Skin, Blood of My Blood

Musical innovation in Jamaica in the 1970s hit seemingly absurd heights, with dub and roots reggae sounds taken to psychedelic, visionary places thanks to producers such as Lee “Scratch” Perry, King Tubby and Prince Far I. Keith Hudson’s name isn’t as widely known as those groundbreaking bass and echo artisans, though the sounds he crafted are, if anything, much stranger, darker and harder to define. Released the same year as Hudson’s Pick a Dub, widely regarded as one of the first ever true dub albums, Flesh of My Skin, Blood of My Blood is a dub and roots creation filtered through haunting atmosphere, eerie sonic architecture and just a touch of apocalyptic spiritualism. Hudson takes on a chilling spaghetti western instrumental on “Hunting,” provides a stoic narration through the ghostly “Darkest Night,” and swirls up some soulful psychedelia on “Talk Some Sense (Gamma Ray)”. It’s the rare reggae album that feels almost supernatural, a glimpse of something you’re not quite sure if you really just witnessed. – Jeff Terich

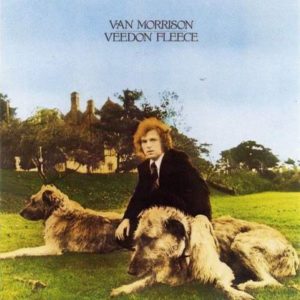

Van Morrison – Veedon Fleece

On Veedon Fleece, the songs of innocence that Van Morrison had sung on his first masterpiece, Astral Weeks, hardened into songs of experience. Perhaps he was suffering from musical burnout (it was his seventh album in four years) or grieving the collapse of his marriage to Janet Planet; perhaps Morrison just made it all up, the way he made up the titular sheep’s pelt as a Holy Grail-like relic. The only person who knows for sure is Morrison himself, and he’s unlikely to divulge the truth, if he’s even conscious of it. Impenetrable yet unmistakably personal, Veedon Fleece feels like Morrison diving deep inside himself in an attempt to recapture the lightning that Morrison first bottled on Astral Weeks. Remarkably, he pulls it off. – Jacob Nierenberg

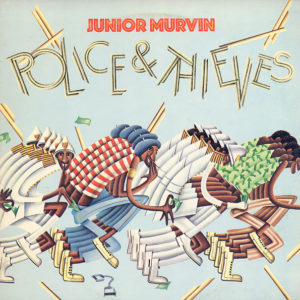

Junior Murvin – Police and Thieves

A few years after Island Records introduced Bob Marley and the Wailers to British and American audiences under the guise of reggae-artist-as-rock-band, Junior Murvin delivered psychedelic soul with a roots rhythm. Anchored by the legendary title track—an anthem against police brutality and harassment and later an equally outstanding Clash cover—Police and Thieves introduced Junior Murvin as a crooner with a velvety falsetto and a rich production backing courtesy of Lee “Scratch” Perry. It’s a mesmerizing swirl of colors and styles, as reflective of the influence of Curtis Mayfield’s innovative Chicago funk-soul sound as that of Murvin’s own backyard, from the deep groove of “Roots Train” to the apocalypse skank of “Lucifer.” – Jeff Terich

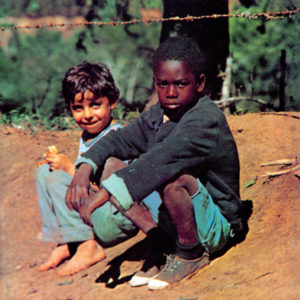

Milton Nascimento & Lô Borges – Clube da Esquina

Punk rock purists love to tell you that repressive right-wing governments and economic upheaval (then and now) is a recipe for great angry music. But Clube da Esquina, the first album from the Brazilian musical collective of the same name, is gorgeous and soothing and ambitious. Milton Nascimento and Lô Borges, two of the country’s most eminent songwriters, created a rich musical tapestry out of bossa nova, psychedelia, folk rock and jazz, and in so doing created a landmark of Brazilian popular music. The lyrics to these songs are full of beautiful things—sunny beaches, colorful dresses, cloves and cinnamon—but also terrible things, from ghost towns (“Os Povos” / “The People”) to abused psychiatric patients (“Trem de Doido” / “Crazy Train”). That these terrible things still exist in our world today is a reminder to fight for the beautiful ones. – Jacob Nierenberg

Pentangle – Cruel Sister

In a moment when most of their peers were incorporating rock influences and turning their attention to original songs, Pentangle instead chose to dedicate their craft to more traditional interpretations of the British folk song. On Cruel Sister they prioritize simplicity over novelty, yet there are so many details to admire in these five expertly-executed tracks: the charming opener “A Maid That’s Deep In Love,” the enchanting solo a cappella “When I Was In My Prime,” the beautifully warm ballad “Lord Franklin,” the sinister unfolding tale of “Cruel Sister,” and the epic, nearly 20-minute theme-and-variations arrangement of “Jack Orion.” The result is among the finest albums to come out of the British Folk Revival. – Emma Bauchner

Linda Perhacs – Parallelograms

While it may not have sold well in 1970, Perhacs instead choosing to pursue a career in dental hygiene, Parallelograms amassed a cult following over the next 30 years, influencing a whole new generation of artists. Listening now, it’s hard to understand why Parallelograms didn’t catch on. Full of atmosphere and light, it marries the best elements of folk and psychedelia. It draws influence from the previous decade, yet is undeniably forward-looking in its production choices and arrangements. Soft folk-pop gems (“Hey, Who Really Cares”, “Sandy Toes”) sit side-by-side with experimental idiosyncrasies (“Parallelograms,” “Moons and Cattails”), and everything blends together beautifully. A 2000 reissue helped cement the album’s status as a classic both of and ahead of its time. – Emma Bauchner

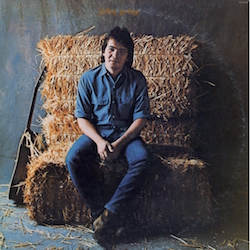

John Prine – John Prine

John Prine’s characters are the kinds of ordinary people who may have lost their vitality and direction, but never their hearts. He can make you feel empathy and compassion for people you’ve never even considered, giving testimony to humanity in all its forms. Prine penned poignant portraits of the lonely and forgotten at every stage of his career, but his debut album remains among his finest collections. It contains some of his best-loved songs and showcases the variety in his craft, from the lighthearted (“Illegal Smile”) to the heartbreaking (“Sam Stone”), to the darkly humorous (“Pretty Good”) to the touching (“Hello in There”). And just one listen to “Angel From Montgomery” is enough to understand why he’s among the greatest ever songwriters. – Emma Bauchner

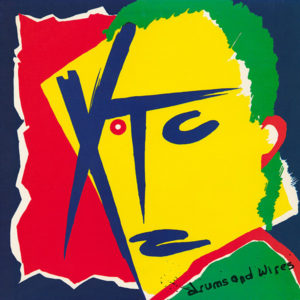

XTC – Drums and Wires

XTC already had two albums under their belt by 1979, and with that some high profile fans (Brian Eno, who said they were good enough that they didn’t need his production assistance), skeptical critics (Robert Christgau, who accused Colin Moulding of writing songs for bored Yes fans, insulting Yes fans in the process by saying they “like to be bored”), and one member in Barry Andrews who saw the band’s implosion as imminent. That never happened, and less than a year after sophomore album Go 2, the band resumed (sans Andrews) with a set of music that comprised their best genuine pop songs to date—their stated goal with the album—as well as some of their most thorny and abrasive post-punk material. The jittery new wave of “Helicopter” builds a bridge back to the group’s earlier singles, but the intensity of “Roads Girdle the Globe” and “Complicated Game” only push the plunger to detonate it on the album’s second side. But on the arpeggio riffs of “Ten Feet Tall,” the jazzy touches of “That Is the Way,” and the sharp riffs of “Real by Reel,” XTC came into their own as some of the best art-pop songwriters of their era. – Jeff Terich

Support our Site—Subscribe to Our Patreon: Become one of our monthly patrons and help support an independent media resource while gaining access to exclusive content, shirts, playlists, mixtapes and more.