The Weeknd : Dawn FM

A preface: We here at Treble have a loosely stated ethical guideline when it comes to reviews and features where we don’t chime in because we feel obligated but instead only write and publish if we think we have a perspective worth adding. What this often winds up meaning is that underground records get our primary attention; it is smaller groups that deserve both critical attention and critical care, having been uncatalogued and often unrepresented to the broader public. The practical end of this means as well that we often wind up opting out of commenting on big records, the Cardi Bs and blink-182s and Drakes of the world, not always necessarily out of antipathy but more that there’s often little additional to say. What this means is that pieces on larger groups, be it the longer series work we’ve done on Rush and U2 or reviews on bigger records by, say, The Weeknd are often decided because we feel we have something to say that’s worth the opportunity cost of briefly turning our eyes from smaller artists and your time as a reader. Time is precious. It’s important not to be flippant in spending or asking for it.

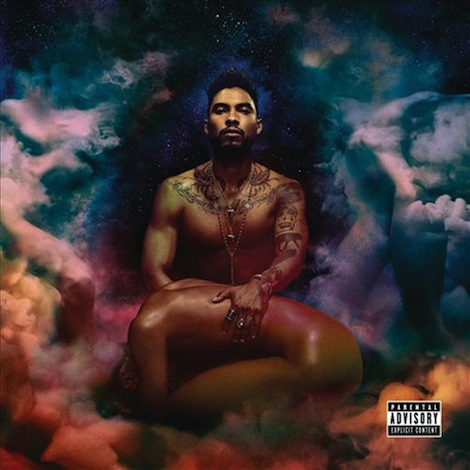

A second preface: There was, for those that remember, a time where this would have precisely been the sort of venue that you’d expect to see coverage of The Weeknd in the first place. His first three mixtapes, when he was still anonymous and not yet known as Abel Tesfaye and briefly a close friend of Drake, were highly lauded in underground publication space and rightfully still are. In fact, for certain sectors, those first three (later released as his proper debut Trilogy) have never been surpassed in quality. Certainly when looking at the arc of his initial studio work, that fact remains true. Kiss Land saw The Weeknd losing critical steam even as the hits started to rack up; Beauty Behind the Madness seems in retrospect to be the moment underground space began to slowly turn their back on him, featuring a muddle of songs designed clearly for pop radio juxtaposed against his typical ultra-black goth R&B. Starboy, his followup, fared even worse in both critical and commercial spaces, being seen by more commercial figures as having arthouse disco and new wave aspirations incongruent with the sound of contemporary radio while simultaneously appearing too polished for underground space.

For some, the ship began to right itself with the EP My Dear Melancholy, a concise return to the sonic space that was his primacy on those remarkable unparalleled first three mixtapes. But, to the frustration of some, this EP was then followed up by After Hours, an album that abandoned those sonics entirely for a reimagined view of the ideas present on Starboy, here refined by a more deft and considered list of collaborators including avant-electronic artist Oneohtrix Point Never into a nervy, cocaine-scented, blood splattered set of disco and synth pop. To some, including a few on staff here, it would read as a muddle, being musically remarkable but paired against a public personna that was increasingly silly and unbelievable. Which leaves us now with Dawn FM, an album that is very nearly explicitly a direct sequel to After Hours, a relation that is absolute in musical terms and nebulous but arguable in thematic and narrative terms.

The issue with this brief history of The Weeknd is that it evades the reality of his work.

In the future, The Weeknd will get a proper reconsideration, where his body of work is reconciled against the canon and his inventiveness and tuneful songs, mixed with his inarguably gothic tenor he’s maintained both in miserablist alternative R&B and seemingly bright and upbeat disco, places him on the firm ground he deserves. And Dawn FM feels like the Trojan horse for those of us who have defended his work nobly against assailants all these years to finally prove to those that slowly defected from his work the worth in returning.

Dawn FM is a loose concept record, like a disco/R&B version of Songs for the Deaf by Queens of the Stone Age. Like that acclaimed rock record, the premise is that of a radio station picked up in purgatory. But while QotSA placed their purgatorial sojourn within the desert environs endemic to their material (as well as Josh Homme’s earlier work in Kyuss), here The Weeknd places the voyage in a traffic jam in a black tunnel following death. The interludes and monologues are framed as DJs and guests guiding dead souls in this purgatorial traffic jam to accept that they are dead in order to move into the light. The songs, meanwhile, are beautifully ambivalent to this frame device, fitting in the narrative as tales from the life of the dead soul in question and out of narrative as compelling arthouse disco earworms. This narrative comes most likely, given both the similar music and thematically related names, after the events of After Hours, which presumably left the main character bloodied and wounded, but in practical terms Dawn FM can be read as a loose sequel to any or even every record by the Weeknd, given the monoform approach to lyrical themes in his work. From his first records to this one, the lyrics have always dealt with a nihilistic indulgence in substances, less for the euphoria of them and more the destruction of the terrifying psyche that exists in sobriety, mixed with a similar self-destructive use of sex, bodies bleeding into each other in blocks of lost time.

Dawn FM makes clear by this narrative, however, an underlying current of gothic music that had always been present in The Weeknd’s work. This was most notable in those earlier records, which often felt like extending The Cure’s dreamy fog-soaked city lights with the sound of the contemporary city, swapping alternative rock for R&B but keeping all other elements static. The bridge from Disintegration and Wish to House of Balloons is fairly obvious when you see it; a brief search through interviews confirms he’s always had higher-brow and more unique sonic influences to his work than some critics give credit, including Deftones, R.E.M. and more. The critiques of his persona-driven work fall apart in the wake of this insight. Earlier work may have been subtle about the connection between the self-destructive main character and gothic narratives of the immolating, decaying self, but Dawn FM at last makes it text, an undeniable aspect of the record. For those aware of the genre bounds of this work, it’s actually quite in keeping with disco and R&B, two genres that have always dealt with searingly bleak themes, including the black-hearted divorce record of Here My Dear by Marvin Gaye, not to mention the constant series of covers of classic country and art pop songs such as “I Can’t Make You Love Me” or “This Woman’s Work.” The usage of this kind of post-Buddhist ghost story, a soul exiting samsara by accepting its sorrows and the coming peace of death, elaborates on the Dionysian post-nihilist joys of dance music and disco that have existed since their dawn.

All of this is set against The Weeknd’s seemingly never-ending capacity for churning out great, heartrending, tearjerking hooks, grooves and timbres that feel like mirrored shades and late night drives and neon reflected in the black mirror of rain-slick roads. These are no longer just cocaine-scented; there is tobacco and whiskey, leather and steel. Synthwave, the whole genre, exists to crudely emulate what Dawn FM naturally is. That it acts as a decoder for the nature of all of The Weeknd’s work is only an added benefit. The fact that it is the second album-length collaboration with Oneohtrix Point Never following 0PN’s Magic Oneohtrix Point Never, sharing a similar radio-themed narrative framing device while pushing each producer to their compositional limit, only further cements the qualities of the record. Sometimes it takes one stray record to remind us how great an artist has been all along.

Label: Republic

Year: 2022

Buy this album at Turntable Lab

Similar Albums:

Langdon Hickman is listening to progressive rock and death metal. He currently resides in Virginia with his partner and their two pets.