On Perdition City, Ulver transcended black metal

Give the People What They Want is a recurring feature and editorial experiment in which Treble explores individual albums as suggested by Patreon supporters. The albums are all over the map—albums we know and love, albums we like but from artists we don’t know that much about, and some that represent an entirely new avenue of exploration for us. Every few weeks, we will dive deep into albums that, by and large, have yet to be canonized.

Ulver hasn’t been a black metal band, at least by one definition, since 1998. There is another definition, of course, by which they have never left that umbrella. Ihsahn, lead creative voice of foundational second-wave black metal trio Emperor and erstwhile solo artist since, has long held that black metal is a methodology and spirit rather than a specific sound, one marked by being a fearless iconoclast as much against yourself as for yourself, as much against your own underground audience as the mainstream world that surrounds you. He has done lifelong work to keep his work tied to the fracturing worlds of black metal even as the shape of his solo material enters often the orbit of progressive music, arena rock, and synth pop. We can see this rubric mirrored as well in each of the other primary figured of the earliest days of black metal in Norway, from Darkthrone’s increasingly idiosyncratic counterrevolution into more and more archaic historical forms of metal, Mayhem’s spiral through the realms of the avant-garde in the wake of releasing perhaps the most quintessential second-wave black metal record of all time, and Enslaved’s development into a musically unbounded modern answer to Pink Floyd. But by this definition of black metal, the embrace of the figure of Satan the first rebel and overthrower of the law, that which overthrows even the self-law and the image of the idealized self, there is perhaps no band more black metal than Ulver, even if Ulver themselves would be the first to reject this sentiment. And the precise moment this became clear was on Perdition City.

Black metal is a curious thing; it is as much a musical style, one that can be defined and examined on a musicological level, as it is a spiritualism, a methodology, a mindset. This is one of the greatest elements it inherits from punk, a term that even in its earliest days bounded groups of radically different musical approaches such as Talking Heads, Blondie, and Ramones—all of whom shared the stage at CBGB—by uniting the impulse that drove them to make their music. These tensions within the notion of what makes a genre, whether it is taxonomic and musicological or spiritual and psychological, are mirrors to the greatest intellectual schism of 19th and 20th century philosophy, that between the analytic and continental schools, itself rooted in a deeper schism rooting back to what the role of philosophy is even supposed to be. Should it model the world in repeatable processes and be able to parse the past? Should it inspire us toward one of many temporary homeostatic planes, these quivering and doomed-to-change ever-evolving states of being, be it sociological or otherwise? This isn’t meant to blow out the importance of the questions of genre or where we draw those lines as much as to display how fundamentally unanswerable this question is even as we dissolve it to baser and baser forms; we are left, inevitably, with a quantum state, that both are true at once, producing differing but ultimately parallel and non-competitive sets of responses to the same question.

Regardless of what measure we use to parse Ulver as a whole and their role within the music of their peers and the spaces they occupied, it is here on Perdition City that they transformed themselves from a black metal band into a Great Band, the same way other figures like The Cure, David Bowie, Coil or Pink Floyd had eruptive moments that dislodged them from the simpler schemas of genre and history into a much broader and more expansive figure. Their role in that position now has been affirmed over and over, from the prog rock of Blood Inside to the expansive David Sylvian worship of Shadows of the Sun to their recent hour-long psych composition recorded as a live album and more. Ulver’s modus operandi in the two decades following Perdition City have seemingly had a singular mission: to affirm Ulver is nothing but themselves, see their work as devoid of any barrier beyond that of desire, pushing themselves via the perpetual Nietzschean self-overthrowing into a sense of limitless self-Becoming.

But to parse how Perdition City plays into this, first we have to roll the clock back to the early days of the group. The group’s first demo Vargnatt was recorded and released in 1993, only a few years after the birth of the second-wave of black metal that came to be the definitive locus of the sound from that moment forward. The historical roots of black metal as a whole have been extensively documented elsewhere but, in brief, the style prior to the pivotal early ’90s recordings by the bands Mayhem, Darkthrone, Emperor, Enslaved and Ulver was a scattered series of approaches blending hardcore punk with the more theatrical and satanic wings of traditional heavy metal as well as the advancements of heaviness and sense of evil found in thrash and eventually death metal. Black metal prior to this eruptive moment, all focused around a little basement record shop in Norway, had been developing in a myriad of different directions; following these recordings, of which Ulver was part, it suddenly and forcefully narrowed down to one path, at least for a time. In retrospect, the later sonic deviations found in Ulver’s larger body of work can already be heard in immature form on Vargnatt but this too is commensurate with their peers, with the prog inclination of both Emperor and Enslaved already emerging in partial form on their shared split EP debut, Mayhem’s turn to the avant-garde present mostly in mixtapes of musical interests produced by the band at the time as well as Darkthrone’s notable early life as a death metal band. This has, in a microcosm, eternally been the issue at play when analyzing or taking influence from those early Norwegian black metal bands, the bare historical fact that their multiplicity and wider set of sonic ideals and interests are perennially overshadowed by how they sounded in one narrow span of years in their teens.

Admittedly, Ulver’s debut record Bergtatt does little to separate the band from this image. Released in 1995, the album was most notable for its mixture of intense black metal with more delicate acoustic folk passages, including use of elements such as flutes and clean vocals, relative rarities within black metal at the time. The focus of the record was likewise a divergence from the then-common image of the genre, eschewing Satanic or vampiric themes for fairy tales, albeit dark and foreboding tonal variants on those tales. One could make a continuum of those five primary Norwegian groups, with Mayhem as the most feral and openly Satanic while Ulver sat on the other end as the most romantic and folkloric, passing through the vampiric mists of guitars clouded by Darkthrone, the classical Satanic peaks of Emperor and the progressive viking metal of Enslaved. Despite these differences, especially on close inspection, Bergtatt still largely fails to strongly diverge with the generative post-Bathory sound of black metal, with each of the five bands in some way embodying shades of that prior Swedish band that laid so much of the foundation that bridged the wildly divergent first wave with the largely convergent early days of the second wave of the genre.

The next two records from Ulver, despite vast sonic differences, are largely considered the two lobes of Bergtatt split in half. Kveldssanger and Nattens madrigal represent the two lobes of Ulver’s sound in isolation, with the former being a condensation of the folk and classical elements (often reading like a black metal Jethro Tull) and the latter being a condensation of the aggressive black metal elements of their sound, erring closer stylistically to In the Twilight Eclipse by Emperor than the more expansive and dynamic work that Enslaved had begun by the mid-’90s. The tightness of these three records is partly explained in the relative haste in which they were written and recorded; by the band’s own account, both Kveldssanger and Nattens madrigal were written in 1995, the same year as their debut’s release. The framing of these works as a trilogy thus becomes retroactively a fairly obvious one, given the strong tie of their birth. Even counting the demo, this earliest phase of Ulver’s life correlates to just around two or three calendar years of writing music, even if the recording and release dates spread much further.

This temporal positioning also explains why, shortly after this, the band’s connections to black metal began to explode. From the outside, their next studio album, Themes from William Blake’s The Marriage of Heaven and Hell, the album immediately preceding Perdition City, read as an abandonment of the faith. Nattens madrigal, the previous album, had been released on Century Media, a larger European label; it was met with strange false rumors, such as that the album had been recorded on an 8-track in the woods but only because the money had been spent purchasing a black Corvette for the band, rumors exacerbated by promo photos depicting the band in black suits hovering around the exact same car. While the neofolk elements of Kvedssanger would eventually be taken up as an almost intrinsic part of future black metal, its presence through Ulver at the time was almost a direct rebuke of the stringent strictures of black metal as it was conceptualized by the mid-’90s, a way of kicking against the wall. That the William Blake album, as the band refers to it, would take these antagonisms a step further feels in retrospect pre-ordained.

It featured the addition of a figure that would turn out to be key in the evolution of Ulver beyond the limits of mere black metal: Tore Ylwizaker, multi-instrumentalist and electronic music composer. Despite my framing earlier of Perdition City as perhaps the band’s greatest break from black metal as a sonic tradition, at least by strict musicological terms, it is in fact this album that is the greatest immediate severance. The record is still in retrospect a progressive music masterwork, featuring a dense and heady mixture of industrial music, art rock, prog, heavy metal ranging from the traditional to the extreme, electronica, and more, all sequenced as a near-gapless double disc record. Its rebellion, though clear on a sonic level, was more subliminal in the realm of aesthetics; the cover appears to be that of a typical more artful black metal record of the late ’90s, matching the evolving aesthetics of the rise of early post-black metal which tended to incorporate art rock and classic prog influence as well as elements of industrial to flesh out the musical palette of black metal. This is ultimately where the limit of this record appears. Even though the William Blake album is a greater sonic deviation in its era and arguably a greater record overall (many hold it, with good argument, as the band’s greatest work even still), it is too easy to recontextualize and subsume back into a black metal framework. After all, even among their Norwegian contemporaries, groups like Enslaved and Emperor were releasing their most grandiloquent and progressive works to date with albums such as Eld by the former, featuring still the longest recorded track by Enslaved, and the masterwork of Anthems to the Welkins at Dusk by Emperor that was the first clear hint at Ihsahn’s greater aspirations toward progressive music beyond the limits of mere black metal.

The last element of the ground for Perdition City‘s birth was the dismissal of the entire band aside from Tore Ylvisaker, leaving him the sole collaborator with Kristoffer Rygg. The other members would go on to join and collaborate with other black metal bands, free to pursue the style of music they had set out to make together on their founding; their previous lead guitarist even appeared on Perdition City contributing guitar parts. But by and large Perdition City was a project created by Rygg and Ylwizaker as a duo, free to pursue the outer limits of the sounds that intrigued them most. From inside the band, especially with the fullness of time, it isn’t hard to see why they would pursue a combination of rainy night trip-hop, downtempo electronica, jazz and ambient music. This era was, after all, arguably the peak of those sounds, with groups such as Portishead and DJ Shadow having produced wildly acclaimed underground records that even threatened to break into the mainstream. Even groups like Radiohead had begun to feel the bite, signaling with them the slow turn of alternative music toward the rich fruits of these sonic expanses. Likewise, artists like Aphex Twin and Squarepusher among others were pioneering IDM as well as its fusion states with ambient music and jazz while further afield the quietly influential world of New Age music, especially that of artists like Enya and Enigma, was coming to bear on the wider aspirations of extreme metal musicians, though their willingness to acknowledge this vector was not to come until some years later.

The difference between Perdition City and the William Blake record are not tremendous or profound. If anything, Perdition City is markedly less maximalist, drawing from a deliberately constrained musical and conceptual pool than its predecessor. Like each previous Ulver record, it was a loose concept album, this time themed as a soundtrack to a fictional film of the same name. Vocals on the William Blake album had already broken from Ulver’s traditional use, which for the initial black metal trilogy were standard extreme metal fair and structural focus of the pieces. With the William Blake album, vocals were incorporated more as an ecstatic texture of the record, following along quite literally to the lines as written by Blake for The Marriage of Heaven and Hell. On Perdition City, that notion of vocals as texture was taken a step further by their low mix in the final album and, in large passages, their complete absence. It is in certain ways a non-metal mirror to the way especially harsh vocals within extreme metal often blend into a broader textural effort rather than an explicative and exegetic conveyance of thought. One rarely sits and ponders what profound truths a death metal band is gargling about and, in the case of Perdition City, the rain-soaked sentiment seems apparent without always knowing the precise wording anyway.

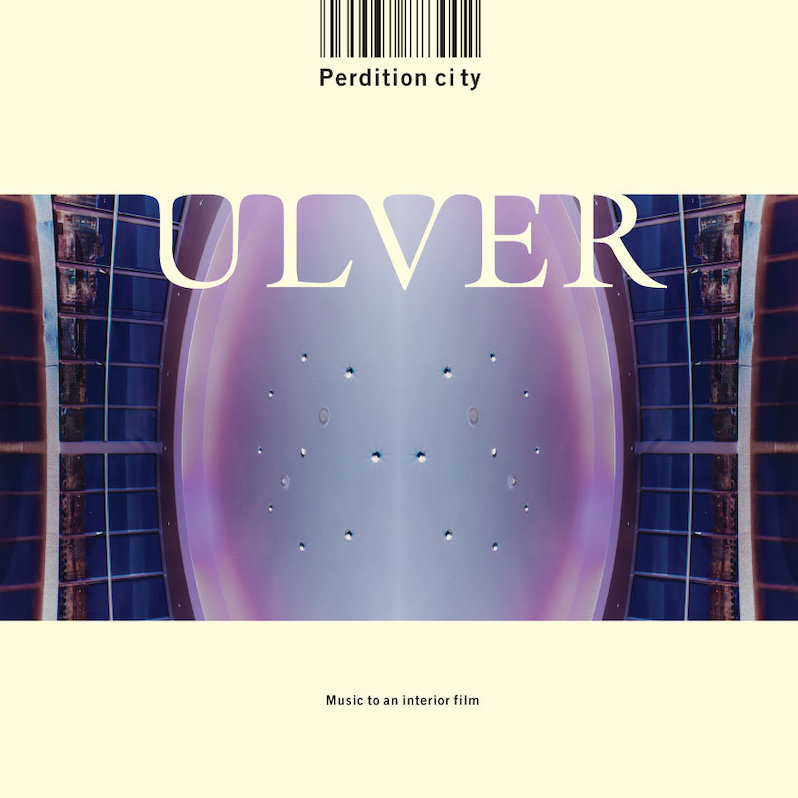

The broader aesthetic shift of the record can best be described as a change of scenery, swooping the camera from the primeval depths of the forest into the heart of the city. While black metal had already begun to tentatively explore methodologies to be both more modern and more contemporary with their concerns, not merely fixating on medievalism or the elementalism of the natural and pagan world, it’s clear in retrospect that Ulver felt a need for a more radical shift to pursue their broader aesthetic interests. This can be mirrored as well in the cover of the record, with its striking whites and blues being a far cry from the stoic and over-Xeroxed saturated blacks and whites of traditional black metal iconography. The font used on the cover of this record for the band’s name would become the font used for most subsequent records both for the band name and titles, indicating on some level a sense of connection forged here that perhaps was amiss elsewhere. The record reeks of rainwater; finally, the image of the black corvette and the suited figures feels fitting. These are songs about urban vampires, the demons of wealth and capital that slink along the streets and stalk in bars, the lycanthropes of the modern world. There is a sense of malice and menace presence here but also, in a shocking twist compared to many black metal bands of the time, an element of sexuality. Very few black metal records feel like black panties bundled next to a box of condoms in a dimly lit high-rise apartment gazing out on the yellow light of streetlamps reflected in the dark mirrored glass of satanic skyscrapers, but Perdition City does.

And yet these ideas were not contained merely to this record. Perdition City was quietly preceded by an EP, aptly titled Metamorphosis, that featured intense techno and experimental electronic soundscapes, utterly devoid both of vocals and of heavy metal of any sort. Likewise, a series of two EPs culled from material laid during the Perdition City sessions would be released shortly after, titled Silence Teaches You How To Sing and Silencing the Singing and eventually collected together as Teachings in Silence, composed of the first attempts by Ulver at unbroken longform music, here a psychedelic ambient and minimal techno endeavor. The throughline of this quiet set of records, all of which produced within a year of each other and exploring the same set of sonic ideals, was that of total ecdysis by the group, the remnants of black metal as we know it falling away like scales from the eyes. Per the liner notes included with Metamorphosis, the band wished to liken their relationship and association with black metal to “that of the snake with Eve. An incentive to further frolic only.” This coheres to an element I discussed previously, that of black metal being not just a set of sounds and traditions to be replicated but also a post-Nietzschean mindset, the act of perpetual musical revolution. The same force which overthrew the rising technicality and polish within “death music”, one of the names of the crusty and punky underground that mixed death metal and goth music and more, the same force which would one day drive Ihsahn to produce progressive music and the members of Darkthrone to undergo radical sonic temporal regression, in fact the very same force that would drive even Mayhem the most sonically definitive of black metal groups to spiral out into the avant-garde, was the same Satanic rebellious force that caused Ulver to eventually overthrow even their origins.

The importance of Perdition City then isn’t that it is the most radical sonic break in the history of the group. As stated before, the William Blake album was in many ways a more radical departure from what had immediately come before, while the EPs surrounding Perdition City both before and after dive more robustly and lustfully into the worlds of experimental electronic music for their own sake. The radicalism of Perdition City and thus the importance of Perdition City is a subtler but no less profound thing: Repetition. Deleuze parses this problem in Difference and Repetition, a philosophy book with a title so dry you just know it’s going to be good, as one inherent to the perpetual organicism of Becoming. Difference, per Deleuze, is a perpetual state, with “differenciation”, with a C, being the process of becoming-different. Divergence, in other words, is an evolutionary predestination; in the world of art, what this means is that tiny variations and colorings outside the lines don’t necessarily overthrow the old, even if they are shockingly different. Take Bad Religion’s Into the Unknown for example, a sloppy but charming psych prog record made by the young hardcore band. After a short breakup, what did they return with? Back to the Known.

What is harder, existentially speaking, is repetition. Imagine, for instance, in an example plucked from the author Borges, a young writer from South America sitting down and writing a novel in isolation that, on review, is exactly the same as Don Quixote. The likelihood of someone inventing a new novel written down to the letter precisely the same as a novel several hundred years old without plagiarism would be shockingly profound; this sense of repetition is, per Deleuze, precise the system-breaking component of Nietzsche’s conception of radical self-Becoming. It is also why, to go back to practical terms, it is not Perdition City‘s radical difference that makes it profound but its radical repetition. It is the album that confirmed to listeners and fans that the straying path found on the William Blake record wasn’t a fluke, that those sonic ideals weren’t to be subsumed back into a largely black metal core. The band was different now; the game had changed.

By and large, the shifted palette produced in the Perdition City era has been the springboard for everything that would come after. Rygg and Ylvisaker are still two of the three core members of the group, with the third, Jørn H. Sværen, joining shortly after the release of this album. This core lineup has remained unchanged in the 20 plus years that have followed, with the group seeing additional collaborators enter but this set trio always being the center. Likewise, though each successive record might be viewed as different from one another, all can be related back to the experiments and concepts found in this era. Hexahedron and Drone Activity, album-length semi-improvised compositions, can be viewed as extensions of the lessons learned and ideals implemented when constructing the 24-minute “Silence Teaches You How To Sing”. The Assassination of Julius Caesar and The Flowers of Evil can be seen as intensifications of the pop components found on Perdition City. Blood Inside, the immediate LP followup, reads like Perdition City fused to a prog rock record from King Crimson. The band was always experimental and, in retrospect, you can hear the thoughts brewing for what they would develop into. The William Blake album may be where they became who they always were, differentiated for the first time, but it was on the repetition of Perdition City that they became the great band Ulver.

Langdon Hickman is listening to progressive rock and death metal. He currently resides in Virginia with his partner and their two pets.

Hey man. As a fan and student of classic music journalism through the years, this is one hell of an article. Really enjoyed reading through and connecting the dots between the influences mentioned along with the boundary pushing aspects of their contemporaries. Thanks for making me relisten and hear this album in a different light. – Brennan

Congratulations on this great article, man. Firstly I think it’s great that a great album like Perdition City is still relevant and provokes a talking around it.

Even though I consider PC their best album in opposition to William Blake, I can see and understand your point of view. William Blake to me is the starting point of their change and then comes the ep etc.

They even denounced the Black Metal term in Metamorphosis artwork, making a note:

“Ulver is obviously not a black metal band and does not wish to be stigmatized as such. We acknowledge the relation of part I & II of the Trilogie (Bergtatt & Nattens Madrigal) to this culture, but these endeavours were written as stepping stones rather than conclusions. We are proud of pur former instincts, but wish to liken our association with said genre to that of the snake with Eve. An incentive to further frolic only..” as you also mentioned.

Anyway, as I said, it’s great we’re still talking about that great album and articles are keep popping up.

Thank you so much for that, man!

Keep up the greta work!