Treble’s 50 favorite bassists

With this list, Treble closes a loop we first opened five years ago. In April of 2012 we gave the drummer some, selecting 50 artists we felt changed—and occasionally perfected—the way we listen to stretched animal skins and flattened brass being beaten with wooden sticks. That initial list begat others which addressed other essential performers in the modern pop/rock band construct: the lead singer, the guitarist and now, at last, the bass player. We’ve filled the final hole in our supergroup lineup, let’s go hit the dream-band studio.

Yes, we know that Bass Player magazine just put out their “100 Top Bassists” issue earlier this year. Not all of our writers claim to be professional musicians, music theorists, or bass technicians, so our list is definitely going to have a more populist focus. What we want out of this survey is to have you spin off to hear great purveyors of the boomstick across all genres. Go research the universe of respected session players. And, of course, hold on tighter to rhythm lines from other artists you already love. This is our low end theory, and we’re sticking to it.

50. John Deacon

Selected by the members of Queen for his reserved mannerisms and quiet approach, John Deacon was the perfect fit between the charismatic flamboyance of Brian May and Freddie Mercury. He never possessed the flashy confidence of his bandmates, but his sheer musical talent spoke for itself. Deacon’s honed playing ability drove Queen’s stadium rock anthems to the top of the charts when his collaborative songwriting with Freddie Mercury began to receive universal radio plays. He was responsible for writing “Another One Bites the Dust,” a definitive Queen tune with a unforgettably classic bass riff. – Patrick Pilch

Watch/listen: “Another One Bites the Dust”

49. Jack Bruce

A fully-entrenched member of the Rock ‘n’ Roll Golden Age, Bruce more or less defined the idea that no self-serious supergroup is complete without a sincere and virtuosic bass soloist. It isn’t easy to reach par with Clapton and Baker, but with Bruce in tow, Cream were every rockist’s dream. If that isn’t enough, his stints with John Mayall & the Bluesbreakers and The Graham Bond Organisation reinforce the legacy, as do his collaborations with Jimi Hendrix, Frank Zappa, and Lou Reed. – Max Pilley

Watch/listen: Cream – “Sunshine of Your Love” ; Jimi Hendrix – “Politician”

48. David Hood

You may not know the name David Hood, but you sure know his low-slung bass. He was the co-founder of the legendary Muscle Shoals Sound Studio in Sheffield, Alabama. As well as an in-demand producer, his real calling was as the bassist du jour, playing on records by Aretha Franklin, Percy Sledge and Etta James. It led to a brief stint in Traffic and a lifetime of high-profile employment on future generations of records. His finest hour was perhaps the unforgettable bassline on “I’ll Take You There” by The Staple Singers. – Max Pilley

Watch/listen: The Staple Singers – I’ll Take You There” ; Traffic – Light Up or Leave Me Alone”

47. Krist Novoselic

As a founding member and bassist of Seattle grunge gods Nirvana, Novoselic experienced the full transformation of ‘90s rock—and also the effects of a bass toss. Born to Croatian immigrant parents, Novoselic was sent to live with relatives in Croatia in 1980, where he began to listen to punk rock bands like the Sex Pistols and Ramones, whose raw and edgy style informed his punchy, highly melodic basslines in songs such as “Lithium” and “In Bloom.” – Virginia Croft

Watch/listen: Nirvana – Heart-Shaped Box”

46. Justin Chancellor

Tool’s second bassist opened a more King Crimson-like door for the band with his intricate and odd time finger work. The shift he brought with him found the band able to reach beyond the tightly coiled riffing of Undertow to something more heady. He can keep up with drummer Danny Carey and has a great tone. On a song like “Schism” you can really hear him shine and actually make prog metal progress rather than a wank-o-thon. – Wil Lewellyn

Watch/listen: Tool – “Schism” ; Tool – “Pushit”

45. Joe Lally

If Joe Lally is remembered for nothing else than his funky-as-fuck, instantly recognizable hook for Fugazi’s 1988 anthem “Waiting Room,” he’d have still cemented his place in the bassist hall of fame. An old-school punk with a knack for the funk, the D.C. bassist helped bring more than a touch of groove and nuance to Fugazi’s sinewy post-hardcore, whether providing the melodic counterpoint for the screeching guitars of “Ex-Spectator” or simply providing a solid backbone to a ripper like “Margin Walker.” – Jeff Terich

Watch/listen: Fugazi – “Waiting Room”

44. Melissa Auf der Maur

Before launching a solo career with the release of Auf der Maur in 2004, the multitalented Melissa Auf der Maur partook in brief stints with both Smashing Pumpkins and Hole in the late ‘90s. Her time with Hole was during some of grunge’s glossiest moments, with the bassist contributing to the distinctively sheened Celebrity Skin. Auf der Maur’s bass highlight comes from the leadoff title track, keeping the song grounded through beneath sleek, highly mixed guitars. – Patrick Pilch

Watch/listen: Hole – “Celebrity Skin”

43. Phil Lesh

Best known for playing bass with and founding The Grateful Dead, Lesh maintained his tenure with the Dead for the duration of their 30-year career, and afterward kept the spirit of their music alive with Phil Lesh and Friends. His talent was influenced by a variety of factors—Lesh started out in music playing violin, then switching to trumpet, and his knowledge and understanding of jazz made its way into his bass playing. – Virginia Croft

Watch/listen: “Phil Lesh and Friends – “Althea”

42. Herbie Flowers

Considered to be one of the best studio musicians of the ‘70s, Herbie Flowers’ resume is both vast and iconic. By the end of the decade, the bassist would play on an estimated 500 hit recordings, including a feature in Jeff Wayne’s musical version of the War of the Worlds. While splitting his time with being a noted member of Blue Mink, T. Rex and Sky, Flowers contributed to Cat Stevens, David Bowie, and Elton John recordings, though his most memorable line may be from Lou Reed’s “Walk on the Wild Side.” – PPi

Watch/listen: Lou Reed – “Walk on the Wild Side”

41. Flea

While the Red Hot Chili Peppers have traded in their punk chants for AOR largesse, Flea’s bass lines remain the best, most consistent thing on the band’s menu. He can pull off crunch, playfulness and melody—to the point of carrying entire songs—with deceptive ease. He’s also sessioned on important cuts for Young MC, Johnny Cash and Alanis Morrisette, played in supergroups Atoms for Peace and Pigface, and can occasionally swing decent trumpet parts and acting gigs. For not being above wearing only a sock on his dick, Flea’s a goddamned renaissance man. – AB

Watch/listen: Red Hot Chili Peppers – “Stone Cold Bush” ; Red Hot Chili Peppers – “Suck My Kiss” ; Red Hot Chili Peppers – “Around the World”

40. Jaco Pastorius

You almost certainly know a bass bore who will happily pharmacologically enlighten themselves and spend the dark hours educating you on the technical superiority of Jaco Pastorius. They are, I’m afraid, right. The very embodiment of ‘70s jazz fusion, he was as responsible as anyone for Joni Mitchell’s majestic jazzy investigations, playing throughout Mingus and Hejira, as well as spearheading the ultimate fusion band Weather Report with Joe Zawinul. His solo records were more interested in funk and Latin influences, but whatever mood he was in, he was accelerating the pace of change. – Max Pilley

Watch/listen: Weather Report – “Birdland”; Jaco Pastorius – “Come On, Come Over”

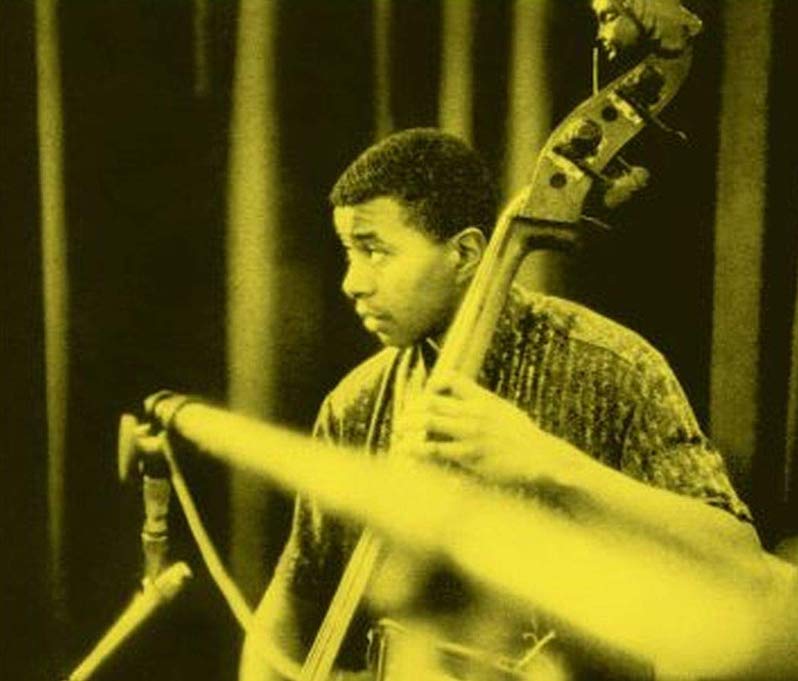

39. Paul Chambers

Pittsburgh-born Paul Chambers began his musical endeavors on the baritone horn and then the tuba before taking bass lessons with a bassist in the Detroit Symphony Orchestra in 1952. Joining the Miles Davis Quintet in 1955 opened him up to a burgeoning jazz renaissance, appearing on Miles Davis’ legendary Kind of Blue as well as with the Wynton Kelly trio from 1963 to 1968. And though he’s been a player on some classic albums, he’s also a stylistic pioneer: Chambers was one of the first jazz bassists to use a bow in performances. – Virginia Croft

Watch/listen: Miles Davis – “So What”

38. Nweke Atifoh

A band like Fela Kuti’s Africa 70 doesn’t really work without a bass player to hold it all together. The Africa 70 was a bit like the J.B.’s or Booker T and the MG’s in that sense—maybe it’s not the first thing you notice, but you damn sure know when it’s not there. Atifoh’s grooves are a constant in Fela Kuti’s output in the late ’70s, providing a roadmap for the musicians on jams like “Zombie” and “Sorrow Tears and Blood” for the other players to go wild. – Jeff Terich

Listen: Fela Kuti – “Zombie”

37. Phil Lynott

The bass of Thin Lizzy’s celebrated leader was the musical equivalent of his band’s perspective. Not given in to flash or showmanship, Lynott simply laid down a consistently sturdy ground line better than anyone in ‘70s hard rock, unassuming on the surface but too well-toned to ignore. But if he felt like it, he’d double the guitar line just to show that he could. – Paul Pearson

Hear: Thin Lizzy – “Waiting for an Alibi”

36. David J

It’s not really about David J’s chops, but the somber grooves he laid down for both Bauhaus and Love and Rockets. He pretty much defined goth bass playing by holding down a creepy bottom for Daniel Ash’s guitar to weave sonic spiderwebs around. His bass lines are hooky, yet he is capable of really pounding when called for. His tone is etched in the memories of every Halloween; Goth bands to come will be trying to mimic his playing long after he’s reunited with Bela Lugosi. – Wil Lewellyn

Watch/listen: Bauhaus – “Double Dare” ; Love and Rockets – “Ball of Confusion”

35. Barry Adamson

Also a member of Visage and Nick Cave and the Bad Seeds (along with work with The Birthday Party and The Buzzcocks), Barry Adamson was best known for implementing dub and soul bass techniques into Magazine’s post punk/new wave fusion. The jazz-punk hybrid style would be later used in the musician’s cinematic solo efforts, with a streamlined focus on Adamson’s more structured electronica influences. “Song from Under the Floorboards” finds the bassist tossing in funk quirks into a straightforward groove, adding high-pitched hooks in a Chris Conley or Paul Simonon fashion. – PPi

Watch/listen: Magazine – “Song from Under the Floorboards”

34. Larry Graham

It’s true that, as the bottom end of Sly & the Family Stone, Graham invented the slap-bass technique that became the downfall of nu-metal bassists who do too many wide squats. But in its context, Graham’s playing was indispensable to his leader’s heavy soul: nimble when he needed the song to move, anchoring when he needed to drive home his point. – Paul Pearson

Hear: Sly & the Family Stone – “Thank You (Falettinme Be Mice Elf Agin)”

33. Ron Carter

It’s hard to name a more crucial sideman in jazz, or for that matter jazz-influenced rock and pop music, than Ron Carter. His nimble double-bass walking style winds its way through countless classics in the Blue Note discography, from Wayne Shorter to Herbie Hancock, and on down to landmark records by Paul Simon and Gil Scott-Heron. His upright bass technique is as much melodic as rhythmic, providing as much soul and passion as proper grounding. His presence also offers instant cred to any album he’s on; as dubious a description as “jazz rap” might be otherwise, Carter’s appearance on A Tribe Called Quest’s The Low End Theory lent the term both legitimacy and gravity. – Jeff Terich

Listen: Herbie Hancock – “Oliliqui Valley” ; Gil Scott Heron – “The Revolution Will Not Be Televised”

32. Roger Waters

There’s constant debate about the provenance of Roger Waters’ bass lines—did David Gilmour play them, and if so, when?—and we’re normally blinded by the light of Waters’ songwriting and storytelling anyway. Yet Pink Floyd would not sound like Pink Floyd without Waters’ compositional skill and solid performance. Some of music’s best rhythm parts only need to define and drive songs, and how can we not think about “Money” without his opening part matching the sound of change and cash registers? And let’s not forget the crazed psychedelic landscape from which Waters and the band sprouted. Acerbic, aloof, and relentlessly intellectual, you may not picture him randomly jamming with anyone, but Roger Waters may be the sharpest avatar for the right player for the right band at the right time. – Adam Blyweiss

Watch/listen: Pink Floyd – “Money” | Pink Floyd – “Chapter 24”

31. Paul Simonon

The Pennie Smith-shot image of Paul Simonon delivering some biblical punishment onstage with his bass on the cover of London Calling is an iconic snapshot in time. He’s a tremendous presence, a six-foot-tall engine providing sheer power and reggae-influenced rhythms to the unstoppable punk anthems the band cranked out during their relatively brief but legendary tenure. His bass is the melodic driver behind that album’s iconic title track, while both his bass and vocal presence led to “Guns of Brixton” being a career standout. As with any other member of The Clash, if you take Simonon out of the picture, then the band simply ceases to exist. – Jeff Terich

30. Bill Laswell

Laswell may be equally celebrated for his production, itinerant mindset and expanding the pool of avant-garde music, but all those concepts are filtered into his bass playing. Starting out in the kindler’s paradise of the Detroit-Ann Arbor corridor of the late ‘60s, Laswell took his catholic palette to New York and formed the gently outré funk group Material. Laswell’s bass lines adhered to funk, but had a sharp timbre and bend that unmasked an Eastern music influence. From there Laswell has been impossible to graph, living the tenets of his Axiom label and “collision music” to the hilt. His bass has found comfortable housing in musical forms both meditative and abrasive, and at times is a commentary on culture itself. – Paul Pearson

Hear: The Golden Palominos – “Boy (Go)” ; Material – “Don’t Lose Control”

29. Chris Squire

If it wasn’t for Squire’s mighty gallop Yes might have sounded like a bunch of elves having a circle jerk. Sure the synths and drumming are epic, but if you listen closely you can hear his thunder gluing the rest of the band’s angular indulgences together. Even when Yes cheesed out and became owners of lonely hearts, he still got the job done. Jimmy Page approached Squire to form a band called XYZ, after John Bonham’s death. So if Jimmy Page wants to work with you, that says a lot even if your album never sees the light of day. – WL

Watch/listen: Yes – “Close to the Edge” ; Yes – “Roundabout”

28. James Jamerson

Just because it’s policy doesn’t make it right. One of music’s great injustices was undone when this man’s name finally came to light as the session bassist for much of Motown’s legendary output from the 1960s to the early 1970s. A boatload of upright and electric bass work for some of the greatest names in R&B and soul allowed him to practice and incorporate techniques previously uncommon in pop, from syncopation and double stops to the open strings of jazz. Equally adept at true low-end support and at flying off into his own melodic orbit, Jamerson’s contributions could program entire radio stations and influence myriad bassists after him. – AB

Watch/listen: The Temptations – “My Girl” ; Stevie Wonder – “For Once in My Life” ; The Four Tops – “Bernadette”

27. John Entwistle

The Ox was The Who’s grounding element in more than just the four-stringed way. As the other three members seemingly acted out as a matter of heredity, Entwistle was known for standing apart from the fray and cultivating as much disinterest as his stance could spare. But Entwistle’s actual playing (and, for that matter, singing) kept up with his bandmate’s immoderation, pushing the beat as feverishly as Keith Moon’s drums, and doubling Pete Townshend’s economic lead guitar in both melody and grace. Entwistle seemed to relish his role of being the one member of British rock aristocracy that almost nobody could identify by sight, but on record his magnitude can’t be argued. – Paul Pearson

Hear: The Who – “My Generation”; The Who – “The Real Me”

26. Mike Mills

The Athens, Georgia band R.E.M. defined and then transcended “college rock” with a hybrid of dusty, jangly, harmonized folk and weird, edgy post-punk elements. Michael Stipe’s lyrical Rubik’s Cubes and Peter Buck’s Rickenbacker gymnastics are well-known parts of the band’s appeal, and Bill Berry’s drumming helped power the dominant first half of their career. That leaves us to discuss bassist Mike Mills. Quietly, he was a driver of some of Buck’s signature sounds and Stipe’s foggy drama—those are his suspensions creating new phantom chords in work like “Sitting Still” and his notes cutting through the clatter of “Orange Crush.” Not so quietly, he also had moments to earn his keep at the forefront of both arrangement and singing, as in the divebombing country beauty of “Texarkana.” His constance and consistency must be considered R.E.M.’s secret weapons. – Adam Blyweiss

Watch/listen: R.E.M. – “Harborcoat” ; R.E.M. – “Life and How to Live It” ; R.E.M. – “Orange Crush”

25. Mark Sandman

Even the smallest changes to common things can help concoct unique and inventive unknowns. Morphine might have been some anonymous trio lost to 1990s alt-rock history were it not for Mark Sandman’s happy creative accidents. He gave their “low rock” subtle power with a gravelly, despairing drawl even in their most aggro moments and, more importantly, by focusing their sound on the two-string bass he would play with a slide. Its rubberband twang could have felt childish in the wrong hands but instead felt sprung from an old soul, giving space and contrast to Dana Colley’s measured saxophone skronk. Sandman led the creation of some of rock’s most distinctive sounds at the end of the 20th century, able to simultaneously suggest film noir, honkytonks and jazz clubs. – Adam Blyweiss

Watch/listen: Morphine – “Thursday” ; Morphine – “Candy” ; Morphine – “Top Floor, Bottom Buzzer”

24. Geddy Lee

It might come as a little bit of a surprise that Lee isn’t further up the list. When it comes to Rush’s brand of radio-friendly prog-rock, though, Lee is untouchable. His most impressive work can be found on the band’s earlier albums, such as Caress of Steel and 2112. While the band would record songs that were more dazzling displays than what is on those two albums, they don’t necessarily rock as hard. All the noodling in the world doesn’t matter if you can’t give a rock song the balls it needs. That is the bass player’s job, and while Lee gets accolades all the time for his ability to multitask on stage, it’s his earlier work that is the most underrated. – Wil Lewellyn

Watch/listen: Rush – “YYZ” ; Rush – “New World Man” ; Rush – “Cygnus X-1 Book II: Hemispheres”

23. John Taylor

Duran Duran achieved an enviable level of fame in the ’80s due to their frequent rotation on MTV—it was the 1980s, and their music videos ruled. But while so much of the attention was paid to their visual presence and vocalist Simon LeBon’s dramatic presence as frontman, the band had some underrated chops, particularly the the nimble playing of bassist John Taylor. Since Duran Duran lined up so much with disco and funk style, Taylor’s bass lines stood out on sexy, sinewy grooves such as those on early singles “Girls on Film” and “Planet Earth.” Though he got his moment in the sun for other reasons as well: In the early 1980s, he made an appearance on People magazine’s annual “Sexiest People” list. – Virginia Croft

Watch/listen: Duran Duran – “Rio” ; Duran Duran – “Planet Earth”

22. Geezer Butler

The closest thing to having a religious experience in my life has been hearing Geezer Butler’s bass on a vinyl copy of Black Sabbath’s self-titled debut record. Hyperbole? (Sacrilege?) Yes and yes, perhaps, but only by a matter of degrees. Black Sabbath’s status as the fathers of heavy metal endows them with the honor of being the Creators, and Butler’s seat at Valhalla was reserved based on that first record alone, his wah-wah jam sessions a psychedelic experience unto themselves—no extra chemical additive necessary. As much as metal is music based around the guitar, however, Butler proved that bass is essential to making any guitar sound any heavier. That being said, Butler’s role in Black Sabbath is far from a supporting one, his low-end magic its own special sort of mystical wizardry. – Jeff Terich

Watch/listen: Black Sabbath – “Black Sabbath”

21. Bernard Edwards

Name one more famous or influential bassline in popular music than Chic’s “Good Times.” Whether being sampled by The Sugar Hill Gang or Grandmaster Flash or being “borrowed” by Queen or The Cure, it feels like it’s never out of the charts for more than a year or so. You begin to feel sorry for the countless other Bernard Edwards parts, so many of them as capable of accessing your spinal cortex as “Good Times,” masters of a borderline sadistic convulsion to make body parts move through space irrespective of rational social conscience or acceptability. “Le Freak,” “I Want Your Love,” “My Forbidden Lover,” “Everybody Dance,” so much to answer for. – Max Pilley

Watch/listen: Chic – “Good Times” ; Chic – “I Want Your Love”

20. Jah Wobble

Inspired by longtime Bob Marley sideman Aston “Family Man” Barnett and egged on by old friend and then-new bandmate John Lydon, Jah Wobble used the first two Public Image Ltd. albums to work out his bass fascination with reggae and dub in a more aggressive rock context. The results were legendary, essentially defining post-punk. Creative differences led Wobble to become a bass mercenary throughout the 1980s and 1990s. He took up projects with The Edge, Holger Czukay and Bill Laswell, recorded alongside The Orb and Primal Scream, and found new chart success leading world-music-inspired band Invaders of the Heart. Constantly busy as an arranger, label head and bass player for sessions, collaborations and his own releases, Jah Wobble has probably forgotten more about the instrument that you or I will ever learn. – Adam Blyweiss

Watch/listen: Public Image Ltd. – “Public Image” ; The Orb – “Blue Room” ; Jah Wobble’s Invaders of the Heart – “Visions of You” (with Sinead O’Connor)

19. Simon Gallup

Though he was instrumental in filling out the group’s legendary goth-rock sound, Simon Gallup was not one of the founding members of The Cure. He joined The Cure as their bassist in 1979, replacing Michael Dempsey, and during his time with The Cure, he also occasionally covered keyboards at live shows. But his bass was a crucial part of the band’s sound, whether in the form of dark post-punk grooves on early singles like “A Forest” or in the form of a much heavier rock sound on 1989’s “Fascination Street.” And though Gallup did briefly quit the band early on, frontman Robert Smith invited him to join The Cure again, and that’s when the band hit their stride—he was even best man at Smith’s 1988 wedding. – Virginia Croft

Watch/listen: The Cure – “Fascination Street” ; The Cure – “Disintegration”

18. John Paul Jones

So you have one of music’s hardest-hitting drummers behind you, what’s a bass player to do? This is answered most clearly on Led Zeppelin songs like “When the Levee Breaks” and “Achilles’ Last Stand”: lay down a groove amid your band’s ever-shifting stylistic landscape. On Houses of the Holy alone Jones was able to lay it on thick as the band moved from funk to reggae to prog-rock. Any rock bass player who doesn’t claim Jones as an influence probably plays pop-punk or wants to be Andy Rourke. – Wil Lewellyn

Watch/listen: Led Zeppelin – “The Song Remains the Same” ; Led Zeppelin – “Ramble On” ; Led Zeppelin – “Dazed and Confused”

17. Colin Greenwood

As one half of Radiohead’s fraternal duo, Colin Greenwood took up the band’s unfilled bassist position after collaborating with Thom Yorke for their “On a Friday” project. Greenwood would go on to become a vital multi instrumentalist for Radiohead, but his 4-string expertise functions as one of the most compelling elements in the group’s approach. His ability to compose nuanced and highly memorable riffs allows his instrument to simultaneously dwell beneath a track’s surface while slipping in and out of its spotlight. Whether Greenwood is harnessing the melodic reigns of “The National Anthem,” or making brief quips between verse and chorus on “15 Step,” his ear for effective hooks seldom disappoints. – Patrick Pilch

16. Holger Czukay

As one of the founding members of German krautrock group Can, Holger Czukay’s pop spin to the band’s experimental formula would push the underground group toward a more approachable sound. Critic Jason Ankeny argues that the bassist “successfully bridged the gap between pop and the avant-garde, pioneering the use of samples,” a technique most notably utilized in Czukay’s drone-collage side project Canaxis 5. Czukay would certainly play a fundamental role in Can’s proclivity for electronic and noise experimentation. However, the musician’s finesse and precision on bass would allow listeners to easily submerse themselves into lengthy works of unconventional psychedelic rock influenced by 20th century classical music. – Patrick Pilch

Watch/listen: “One More Night”

15. Robbie Shakespeare

Robbie Shakespeare straddles two distinct eras in Jamaican music. In the 1970s he was an indispensable session player, his mark left on records by Bunny Wailer, Dennis Brown, Black Uhuru and countless others. His place in history and on this list was perhaps secured, though, by his work as one half of production duo Sly and Robbie. They were at the vanguard of the “rub a dub” style which placed digital programming and computer assistance at the heart of reggae production. Records by Grace Jones, Herbie Hancock and Ini Kamoze were unfamiliar and challenging in their day. Shakespeare and Sly Dunbar would move on to spearhead dancehall in the 1990s, producing Chaka Demus & Pliers’ breakout recordings. – MP

Watch/listen: Sly and Robbie – “Boops” ; Grace Jones – “My Jamaican Guy”

14. Les Claypool

Once upon a time in high school, a friend of mine played me a song called “Jerry was a Race Car Driver.” Granted, I had not yet been introduced to The Residents or King Crimson, but this was Primus, this was Les Claypool, and this was pretty mind-blowing. In this high school phase I saw him not once but twice on the Sailing the Seas of Cheese tour, and what happened on stage was more impressive that came out of my Walkman. He played the guitar riffs to “Master of Puppets” on his bass. Sure, it had as many strings as a guitar, but remember, this was the early ‘90s. It was much more of a novelty then. – Wil Lewellyn

Watch/listen: Primus – “Jerry was a Race Car Driver” ; Primus – “Harold of the Rocks”

13. Paul McCartney

It can be easy to overlook Paul McCartney’s skills as a bassist for two excuses: (a) He was in the Beatles, their myth still writ so large deconstructing it seems counterproductive, and (b) Paul plays basically all instruments ever made, most of them quite well. But if one sets the mania aside and pays close attention to certain Beatles and Wings songs, McCartney’s bass moves are almost blindsiding. He approaches the instrument from a composer’s perspective: McCartney knows the essence of melody better than any of his peers, and his incredibly mobile bass lines for tracks like “Something” and “Taxman” casually take flight off harmonies most players would have to fight to locate. Even decades-long fans (i.e., this writer) drop their jaws when they’re concentrating on Paul’s bass for the first time, another way the Beatles are the gift that keeps on giving. – Paul Pearson

Hear: The Beatles – “Rain” ; The Beatles – “Something”; Wings – “Silly Love Songs”

12. Esperanza Spalding

There’s no point in dancing around it—Spalding is a musical prodigy. At the age of five, she was playing violin in the Chamber Music Society of Oregon. After teaching herself a number of instruments, she earned scholarships to Portland State University and Berklee College of Music, and since then has won four Grammy Awards, most importantly the Grammy Award for Best New Artist in 2011—and she was the first jazz artist to win the award. Regarding her choice to focus on bass, she has said that it was not a choice, the bass “had its own arc.” That arc has carried her into different styles and genres throughout her career so far, from her more traditional jazz sounds early on to the psychedelic funk rock of her outstanding 2016 album, Emily’s D+Evolution. Spalding sings while she plays, and does so in three different languages: English, Spanish, and Portuguese. – Virginia Croft

Watch/listen: “Overjoyed”

11. Thundercat

Like some of the most prolific bassists on this list, Stephen Bruner (a.k.a. Thundercat) has contributed to an incredible roster of artists—Flying Lotus, Erykah Badu and Kendrick Lamar to name a few. Born into a musical family, his career began early. At 15, he would score a minor hit in Germany with his boy band No Curfew, prior to joining the crossover-thrash group Suicidal Tendencies. Thundercat’s stylistic range gives him an edge over his contemporaries, honing his wildly dexterous and unique playing style. I can’t watch the attached performance of Thundercat anymore. It makes me feel wildly unaccomplished. – Patrick Pilch

Watch/listen: “Tron Song”

10. Kim Gordon

Technically speaking, Kim Gordon is a multi-instrumentalist. In her band Body/Head as well as on the last handful of Sonic Youth albums, Gordon swapped out the rhythmic pounding of bass for more ethereal melodic sounds via guitar. For that matter, Gordon is as much a vocalist and poet as anything else, having lent her voice to roughly 40 percent of Sonic Youth’s material during their 30 years together. As a bass player, though, Gordon’s presence is an undeniable one. From the band’s genesis as progenitors of accessibly noisy no wave fuckery, she played heavy, dropping some terrifyingly thunderous notes on early highlights like “Death Valley ’69,” only to evolve into a more radio-friendly player with a knack for buttery rhythmic groove on singles like “Dirty Boots” less than a decade later. Certain bassists earn their due by signature sounds and inimitable techniques. With Gordon, it’s more about versatility and her ability to go somewhere new with each phase of the band’s career. There’s never any doubt that you’re hearing Gordon’s playing, it’s just not always obvious why. – Jeff Terich

Watch/listen: Sonic Youth – “Kool Thing”; Sonic Youth – “Death Valley ’69”

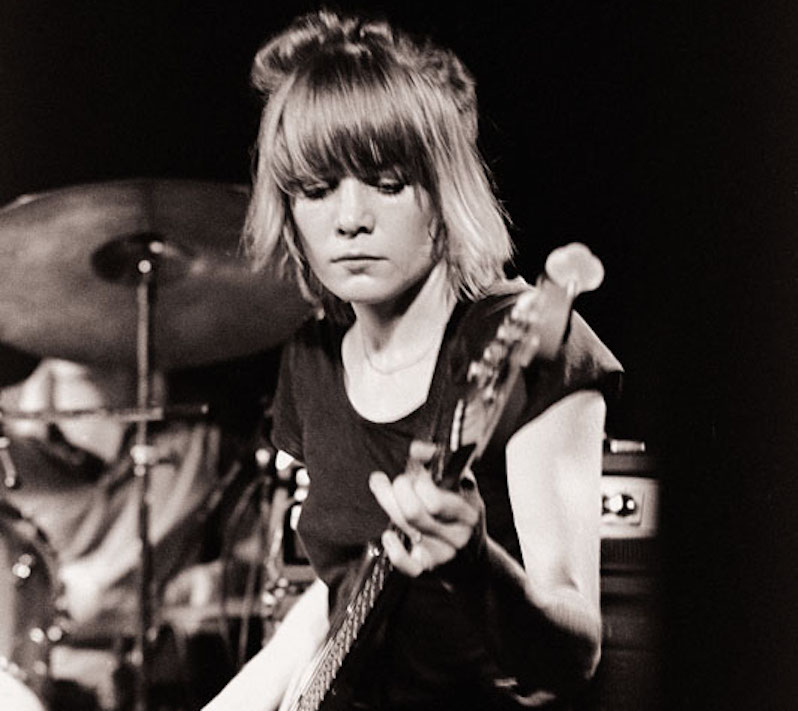

9. Tina Weymouth

Growing up, Martina (Tina) Weymouth spent her childhood traveling around the world with her parents. Her mother was born in France, and her father was a U.S. Naval officer, a job that would require frequent relocations all over the globe. As a result, Tina would never form lasting relationships, causing her to become painfully shy in her youth. It wasn’t until she lived in Manhattan with her brother in the early ‘70s would she begin to open up. After applying to Rhode Island School of Design, her transformative journey as an artist would find Weymouth starting a band with her studio mate Chris Frantz, whom she quickly started dating.

Frantz played drums in a band called The Artistics with guitarist and singer David Byrne. The three would move to New York City and form Talking Heads after Weymouth would teach herself the bass in just a few months. Weymouth’s funk-punk fusion pioneered a style of art rock that would influence generations of musicians to come. Talking Heads would chart with bass-heavy hits like “Once in a Lifetime” and “Burning Down the House,” but Weymouth’s distinct grooves can be most easily heard on “Cities” from 1979’s Fear of Music. – Patrick Pilch

Watch/listen: Talking Heads – “Cities”

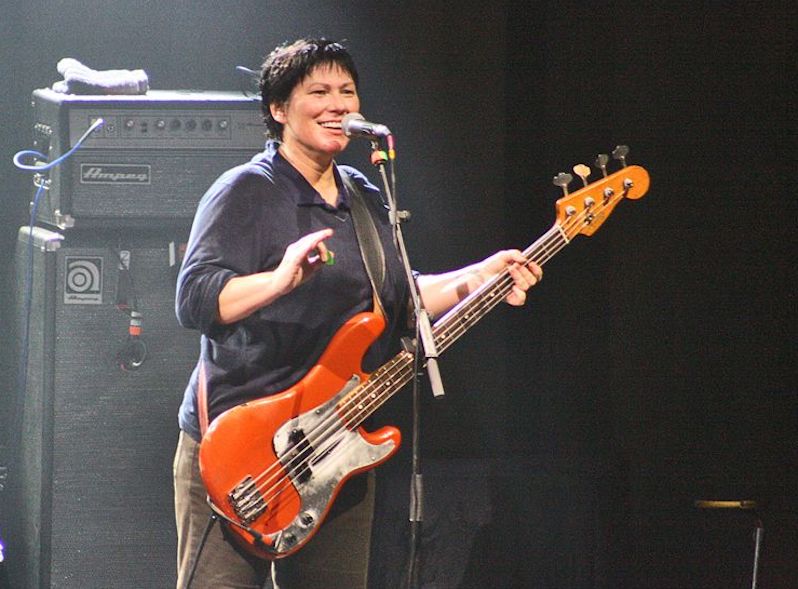

8. Kim Deal

Though she’s one of the most iconic bassists in alternative music history, Kim Deal’s writing, playing and charisma could not be contained by her Pixies work. Her eventual trajectory culminated in the thrilling and lacerating records of The Breeders, the band she formed with Tanya Donelly from Throwing Muses and later Kim’s twin sister Kelley.

From the day she joined Pixies in 1986, responding to an advert for a fan of Hüsker Dü and Peter, Paul and Mary, a marriage of punk and melody has been her trademark. Much like Peter Hook in New Order, her basslines could often be described as the lead instrument, propelling the melodic lead whilst still pinning down the tempo. If that wasn’t enough, her vocals on tracks from “Gigantic” to “Velouria” became fundamental to the band’s aesthetic.

Her presence in a male-dominated world was also not unnoticed. She was credited on Pixies debut album Come On Pilgrim as Mrs. John Murphy, a sly swipe at the controlling patriarchy. – Max Pilley

Watch/listen: Pixies – “Here Comes Your Man” ; The Breeders – “Cannonball”

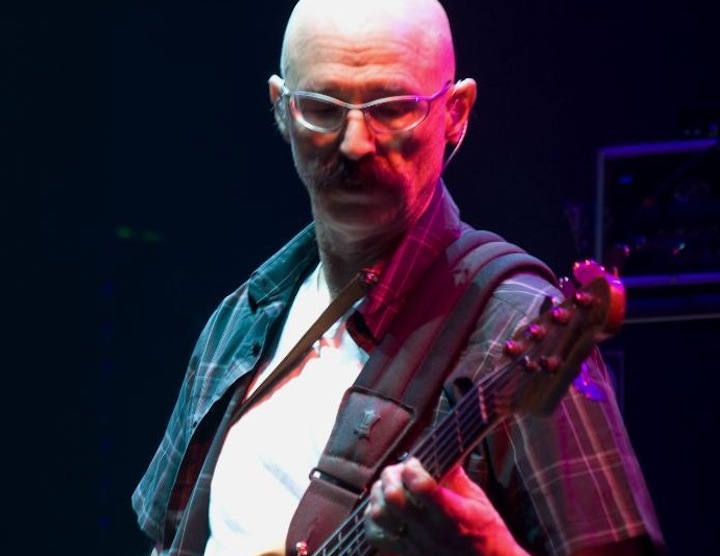

7. Tony Levin

Boston bass player Tony Levin earned his earliest sideman cred with jazz flautist Herbie Mann (if you remember Will Ferrell’s exploits from Anchorman, you know the sound) before sessioning on Bob Ezrin-produced albums for Lou Reed and Alice Cooper. Ezrin then introduced Levin to Peter Gabriel, who was just re-entering the music world after leaving Genesis and starting a family. He’s been a constant fixture on Gabriel’s albums and tours since then, providing wobbly, futuristic lines on electric upright bass and co-inventing “funk fingers” to slap at his instrument like a drum.

Levin also managed to take more session detours with John Lennon, David Bowie and monsters of prog like King Crimson, Yes, and Pink Floyd, as well as put together a catalog of solo work and collaborative band releases. Forty years on, Tony Levin has parlayed one timely connection into status as one of the most killer silent killers in music, his distinctive look, sound, and tools helping him cut an imposing figure out of the normally anonymous context of the backing band. – Adam Blyweiss

Watch/listen: LIquid Tension Experiment – “Acid Rain” ; Peter Gabriel – “Big Time” ; Paul Simon – “50 Ways to Leave Your Lover”

6. Andy Rourke

Regardless of what happens in the five entries you read after this, I’m just going to declare it: Andy Rourke is the greatest bassist ever. The main fact that supports this claim is the fact he played in The Smiths, who are the greatest rock band ever. While Johnny Marr promoted playing distortion-free guitar during a time Eddie Van Halen was masturbating in arenas across the pond, it’s Rourke who holds those songs together.

Having played in a Smiths tribute band myself, I can attest to the fact that when you deconstruct their songs and study what each instrument is doing, it’s Rourke who worked overtime. It’s his rubbery bass lines that give songs like “Girlfriend in a Coma” a dancey bounce. His playing is melodic and complex at the same time, allowing Marr to ring out chords in more unconventional and atmospheric manners than if they had somebody who just kept the bottom end in the pocket. Rourke’s bass defines The Smiths as much as Morrissey’s voice—that’s the highest compliment I can give a musician who is not David Bowie. His playing continues to influence countless indie-rock and post-punk bands with phrasing that’s equally melancholic and merry. – Wil Lewellyn

Watch/listen: The Smiths – “Barbarism Begins at Home” ; The Smiths – “This Charming Man” ; The Smiths – “Rusholme Ruffians”

5. Mike Watt

Mike Watt’s place in the post-punk narrative is confounding enough that Watt even did a solo album whose title addresses the ambiguity: Ball-Hog or Tugboat? His work with The Minutemen blew up the playbook for punk bass players, calling upon foundational funk runs and spasmodic bursts. His tenure in fIREHOSE, and the above-mentioned album, employed some of that wildness with an appreciative nod to the instrument’s traditional anchorage role. His later high-profile work with the Stooges and, this is not a typo, Kelly Clarkson found him in strict service to the song and performer, but was as recognizable a part of the spine as anything else. And then there are Watt’s multiple side projects in which he constantly searches for new context. The key to Watt’s greatness is his relentless work ethic and dependence on the unknown. He’s a nomad who started his trip with a terrific skill set, but still thought there was more he could accomplish. Thurston Moore admired Watt simply because he approached his playing as his “job,” a point of view that disarmed arrogance and its gilded trappings. Thirty-five years later he’s still on the clock, generating as much interest in his artistic principles as his bass playing. – Paul Pearson

Hear: The Minutemen – “The Glory of Man” ; fIREHOSE – “If’n”

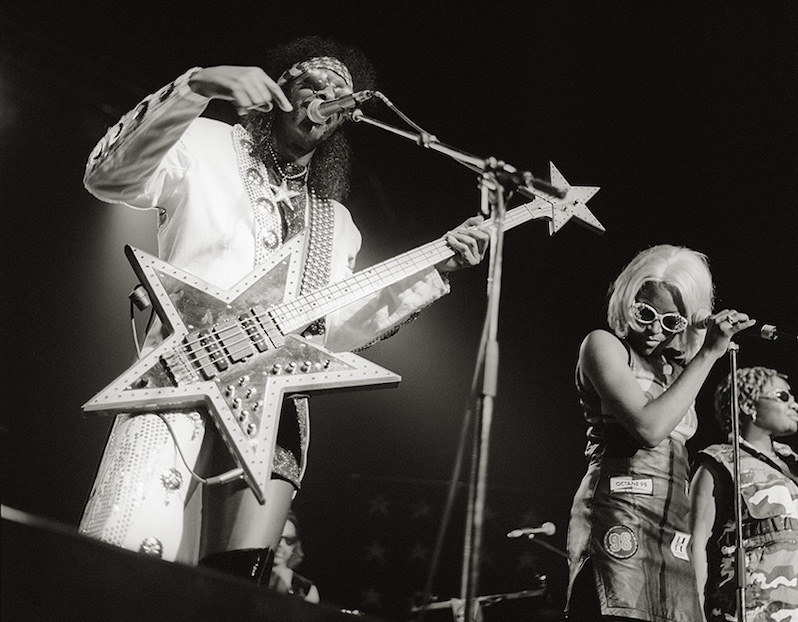

4. Bootsy Collins

The Cincinnati kid was pulled from his band The Pacemakers to serve in James Brown’s backup band, the JB’s. He only lasted 11 months—Brown was a stickler for neckties and Bootsy wasn’t having it—but he laid down the bass for some of the Godfather’s most crucial transitional tracks: “Sex Machine,” “Super Bad,” “Talkin’ Loud and Sayin’ Nothing.” Even after leaving, William Collins preached Brown’s all-encompassing philosophy of funk, “The One,” when he joined up with George Clinton’s Parliament-Funkadelic collective. This makes Bootsy the thread between the two most influential music acts in funk history. Collins showed some of his flash with the JB’s, playing along with the groove, content to do the occasional pop when the boss would allow it. But with P-Funk and his solo work Bootsy revolutionized his style: playing quick-swinging fills at both the low end and the octave up, showing great fluidity and bends while not disrupting the force of The One. (There’s a reason it’s called Bootsy’s Rubber Band). Collins interpreted Clinton’s code of musical liberation as cleanly and wholly as anyone could have, and by occasionally looking back over his shoulder at the roots of funk he helped write the source code for all future R&B generations. – Paul Pearson

Hear: James Brown – “Talkin’ Loud and Sayin’ Nothing” ; Parliament – “P-Funk (Wants to Get Funked Up)” ; Bootsy’s Rubber Band – “Stretchin’ Out (In a Rubber Band)”

3. Sting

Gordon Matthew Thomas Sumner, better known as Sting, the lead singer, and principal songwriter for The Police from 1977 to 1984. Just as important, though perhaps discussed less, was the fact that he was the band’s bass player, providing a rhythmic grounding between Andy Summers’ prog-like guitar hooks and Stewart Copeland’s dub-on-the-moon drum theatrics—though let’s be honest, all three were showboats. While he’s received a long list of awards, perhaps Sting’s strongest facet is his ability to be so diverse in his musical expressions. This shines through in Police albums Zenyatta Mondatta and Ghost in the Machine, with their clear reggae influences and persistent grooves. He could hold down a solid pulse when he needed to, but when given the opportunity to drive some hard funk in a number like “Demolition Man” or go reggae atmospheric on “Walking on the Moon,” Sting showcased his instrumental abilities that go far deeper than the charisma of a frontman. – Virginia Croft

Watch/listen: The Police – “Demolition Man” ; The Police – “Walking on the Moon”

2. Charles Mingus

The most celebrated and influential bassist in jazz, Mingus did as much to forge progress from the hard bop generation into a freer, more improvisational philosophy as anybody. Beginning as a prodigious standup bassist in the 1940s, he earned a reputation touring with Louis Armstrong and Duke Ellington. By the time he was his own bandleader the following decade, he had begun to incorporate his fixation with gospel and blues into his playing. Tracks such as “Better Git It in Your Soul” kept an ear close to the late-’50s changes in popular music as much as it did to classical traditions.

Vintage albums Mingus Ah Um and The Black Saint and the Sinner Lady embraced the so-called “third stream,” a hybrid of jazz and classical, composition and improvisation. On Mingus’ watch, the bass was no longer a metronomic control, liberating it to the point that it was as capable of exploring and exclaiming as any trumpet or saxophone. He expanded the role of the instrument, insisting that many of his predecessors had been playing within themselves. Indeed, he once memorably condensed this idea, claiming, “I really can’t enjoy music if I have to play boom, boom, boom, boom all night.” – Max Pilley

Watch/listen: Charles Mingus – “Better Git It in Your Soul” ; Charles Mingus – “Track C – Group Dancers”

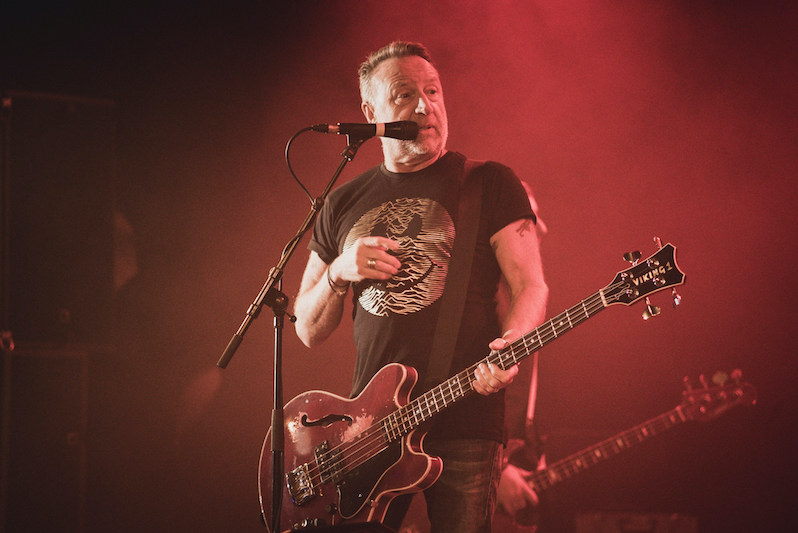

1. Peter Hook

“Transmission,” the iconic 1979 single by Manchester post-punks Joy Division, begins with an unmistakable sound: Over a gentle whoosh of synth ephemera, Peter Hook pounds out a staccato two-note bass pattern, laying down a so-simple-it’s-genius blueprint that would become the signature sound of post-punk, borrowed countless times by countless artists, an almost foolproof method of building sonic cool.

“Ceremony,” the legendary 1981 single by Manchester post-post-punks New Order—originally written when three-quarters of the band comprised Joy Division, likewise begins with an unmistakable sound: Before any other instrument is introduced, Hook plucks a high-on-the-neck pattern that sounds more like a lead melody than a rhythm track, introducing what would become a signature technique that not only set New Order apart but turned the concept of bass playing entirely upside down.

“Age of Consent,” the essential 1983 album opener to New Order’s Power, Corruption and Lies, like those other two post-punk monoliths also begins with the sound of Peter Hook’s bass, and by this point, it wasn’t just a unique characteristic of the band’s music, it was a defining aspect. As Hook, Bernard Sumner, Stephen Morris and Gillian Gilbert evolved from a post-punk band in a state of transition to a pioneering synth-pop group with an ear to the dancefloor, Hook’s bass became a beacon—a badge that the band wore proudly as if to signify to listeners, We’re New Order and We Do Things Differently. “Age of Consent” is a template of sorts for New Order’s instrumental dynamic (up until Hook parted ways with the group a few years back), putting the bass in the role of lead guitar rather than as a low-end anchor. The miracle of it all is how every piece remains essentially intertwined without any open space feeling neglected or uncovered. Peter Hook could do simple basslines, and did when he needed to, but his greatest accomplishment—one so noteworthy it put him at the top of our rankings—was changing the way that listeners think about bass as an instrument. Or, perhaps more curiously, blurring the line between bass and guitar so as to question whether conventional instrumental roles, as we know them, are meant to stay that way. – Jeff Terich

Watch/listen: New Order – “Age of Consent”; New Order – “Ceremony”; Joy Division – “Transmission”

What about The Great STANLEY CLARKE The Greatest Bass player in the world.

Where’s Steve Harris the bassist for the mighty Iron Maiden who’s signature gallop can be heard on Phantom of the Opera (1980) to the Red and the Black (2015) in a career spanning 40+ years his ommision from your list is a grave error

Jaco # 40 are you out of your fucking mind

I seriously miss Will Heggie, JJ Burnel and Jah Wobble in this list!