Critic Simon Reynolds once said that being a Throbbing Gristle fan was “like enrolling in a university course of cultural extremism.” That’s an apt way to understand industrial music in its genesis—no pun intended. Throbbing Gristle, who coined the term “industrial,” began as a performance art collective after coming up in the world of psychedelic rock; Peter “Sleazy” Christopherson was even part of the British design collective Hipgnosis for a time. The group’s early performances shocked more than entertained, criticized by conservative politicians as “wreckers of civilization.” But in transitioning into music, what Throbbing Gristle created wasn’t any less confrontational. One need only listen to the group’s infamous murder drone “Slug Bait” once to understand the kernel of industrial music: Musical extremes colliding with social taboos.

The sound and shape of industrial music has changed and evolved in countless ways since Throbbing Gristle first emerged in the 1970s, to the extent that the genre’s name has often been understood, if erroneously, as a description of its sound. Clanging metal, harsh noise, heavy pulsing rhythms—this is how we often understand industrial music, through the dancefloor terror of Skinny Puppy, the machine-metal of Ministry, or the artful cacophony of Einsturzende Neubauten. But over time it spread to farther extremes—sound collage, pure noise—while also infiltrating pop music. Where the rise of industrial music and artists like Cabaret Voltaire and Coil rose in large part out of post-punk, toward the end of the ’80s and early ’90s, the influence of industrial music could be heard in pop music (compare the production on peak-era Ministry with Janet Jackson’s Rhythm Nation 1814) and eventually crossing over into hip-hop. All the while, industrial became a place to explore transgressive ideas while also becoming a platform for social commentary (Throbbing Gristle’s use of the term “industrial” spoke in large part to how capitalist innovation adversely affected their home city of Hull) as well as becoming a haven for queer and marginalized communities. (Though, frustratingly, a handful of figures in industrial music became notorious for all the wrong reasons.)

Industrial music is also intense, and often veers toward the terrifying. Early signature recordings from Nurse With Wound and Throbbing Gristle employed dark textures and horror-like atmospheres. Coil actually recorded a (rejected) score for Hellraiser. Nine Inch Nails—the biggest pop crossover that industrial’s ever seen—even made a short, fictional “snuff” film as a promo for 1992’s Broken. Industrial music is rarely ever safe or comforting, which makes it the perfect sphere of music to explore during Halloween week.

As with similar features we’ve done in the past on Alt-Country, Synth Pop or Jazz Fusion, this history of industrial isn’t intended to be an exhaustive list of all of the best industrial songs or recordings. We also had to make some decisions as to how broad our coverage should be, like whether it would include power electronics (a little bit) or neofolk (we opted not to, for musical reasons as well as the far-right nature of some of its best-known acts). What we have in the end is an attempt to tell a story from the earliest experimentalmusique concrète and cacophonous psych acts on up to the terror pulse of the present day. These are industrial music’s roots, inspirations, landmarks, triumphs and the songs upon which its influence has been imprinted. Follow us on our dizzying descent.

Pierre Schaeffer – “Etude aux chemins de fer” (1948)

As World War II drew to a close, the radio and recording studios of France afforded Pierre Schaffer a unique opportunity to intersect his interests in sonic art and science. He helped establish the genre of musique concrète—transforming atypical sounds into something resembling music, and musical sounds into the atypical. The first of five Schaffer compositions introducing this electroacoustic music to the world, it takes sounds from trains and modifies them in ways that would herald concepts like looping, sampling, and ADSR parameters. The results may sound now like a young relative playing with a modern toy, but consider the Herculean effort of manipulating equipment that filled buildings and rooms to create even the smallest technological revolution. “Etude aux chemins de fer” and its companions also carry with them the kind of grain and echo that haunt great dark music to the present day. – Adam Blyweiss

Cromagnon – “Caledonia” (1969)

Pounding drums, radio wave static, sampled orchestral music, fuzz guitar, bagpipes(!) and something approaching a black metal vocal hiss—in 1969 there was essentially no frame of reference for this combination of sounds, certainly not one so heavy and intense. New York City’s Cromagnon emerged during psychedelic rock’s peak period of experimentation, but their own approach still sounded miles apart from what bands such as Pink Floyd or The Doors were doing, the harsh, buzzing, willfully abrasive din of “Caledonia” a unique entry that had no peers and few immediate descendants. But the seeds they planted sprouted years later in the ritualistic clang of Einsturzende Neubauten and the acerbic machine-rock of Ministry. There just wasn’t a word for this kind of music when they made it. – Jeff Terich

Suicide – “Frankie Teardrop” (1977)

Although not an industrial band per se, the proto-electronic darkness of Suicide’s “Frankie Teardrop” is a template for early Industrial music, its experimental leanings and harrowing intensity. Released in 1977, it’s an eerie and powerful song about the titular Frankie and his descent into complete madness, homicide, and suicide. “Frankie Teardrop” probes some of the darkest boundaries that could have been set for the time, rooted in a rhythm that is faster than most proper industrial tracks released over the next eight or so years. And while the genre has spread out into some pretty tense and abrasive avenues, the song’s run time of ten minutes—ten minutes of escalating and persistent screaming—would be an endurance test even now. From its nightmarish yet memorable droning, to its shifting experimentation and lyrical themes, “Frankie” is a vision of what industrial would become, all its horrors properly included. – Brian Roesler

Throbbing Gristle – “Hamburger Lady” (1978)

Formed out of performance art troupe COUM Transmissions, Throbbing Gristle coined the term “industrial” but they didn’t limit what that entailed, their early recordings ranging from noise to sound collage, disco, synth-laden kosmische and exotica. “Hamburger Lady” is none of these, but rather a harrowing series of drones made to sound like medical equipment and the slow march of death, as Genesis P-Orridge narrates the horrific details of a burn victim through eerie vocal effects. For Throbbing Gristle, the idea of “industrial music” didn’t specifically mean that of factories and assembly lines, but here, the British provocateurs make a symphony of machines—not the corrugated steel and aluminum of some of industrial’s most avant garde pioneers but rather the cold, banal accompaniment to real life horrors. – Jeff Terich

Cabaret Voltaire – “Seconds Too Late” (1980)

Sheffield’s Cabaret Voltaire hit a lot of milestones in industrial’s early evolution, from synth-punk to cacophonous dancepunk to icy EBM, though their 1980 single “Seconds Too Late” remains a singular contribution to the canon. A cold, robotic and deeply unsettling piece of electronic hauntology, “Seconds Too Late” lurches with menace and shimmers with discordant melody, like the sound of ghosts rising from a post-apocalyptic battlefield. It’s strangely beautiful in its discordant darkness, neither the band’s most well-known track nor their most accessible, but one whose eerie echo ripples through industrial’s cavernous halls some 40 years on. – Jeff Terich

Killing Joke – “Wardance” (1980)

Where for Godflesh their work could be summarized in a single thesis work, Killing Joke is somewhat more elusive. Take “Wardance” here as more gestural than definitive, a glimpse of their gothic post-punk that is as foundational to understanding the evolution of the more industrial and gothic wings of punk developments as well as, shockingly, the history of extreme metal. Killing Joke are in many ways the Velvet Underground of the ’80s, immeasurably influential in a million fields that sometimes have very little surface similarity to their work. The reason is clear: “Wardance” is primal, rebellious, snotty, but cybernetic, ridden with sigils and signs of ceremonial magic, run through with an I-beam. It feels like the brute conflict of the distant past against the distant future in the perennial warzone of the perpetual present. It proves industrial music can be not only brutal, spiritually bleak, the sound of rotting walls and crushed bones and terminal illness; it can be a bloody smile. – Langdon Hickman

D.A.F. – “Der Mussolini” (1981)

Descendents of Suicide’s synth-punk minimalism, dressed up in homoerotic imagery and with lyrics intended to turn heads and cock a few eyebrows, D.A.F. (Deutsch Amerikanische Freundschaft) laid out the blueprint for Electronic Body Music with 1981’s Alles Ist Gut, and its dadaist hit “Der Mussolini.” A mockery of fascism that calls for its audience to “do the Mussolini” in a kind of sweaty, hypersexual dancefloor ritual, the track is made somewhat more disorienting and sinister due to its slightly out-of-tune synth programming. The fact that there are young adults with samplers and leather jackets still making tracks that borrow from its cheeky, controversy-baiting approach only speaks to how visionary it was. – Jeff Terich

Nurse With Wound – “Homotopy to Marie” (1982)

The rare entity for which listening to different albums can tend to suggest different artists altogether, Stephen Stapleton’s Nurse With Wound doesn’t have a defined aesthetic so much as a pull toward abstraction and non-conventional approach. Homotopy to Marie isn’t the first Nurse With Wound album, but it’s the one Stapleton considers his proper debut, a creaking haunted house of jump-scare crash and screech, disembodied voices and percussive scrape. The title track is its deeply unnerving centerpiece, samples of a woman saying “Don’t be naive, darling” and a little girl complaining of a funny smell providing rare moments of absurd humor amid the ominous drone of a cymbal. It’s perhaps as non-musical as industrial music gets, but there’s a peculiar sort of magic in how the unpredictable recurrences of similar sounds eventually take on more menacing qualities, the eventual climax feeling like the moment when the shape finally emerges from the shadows. – Jeff Terich

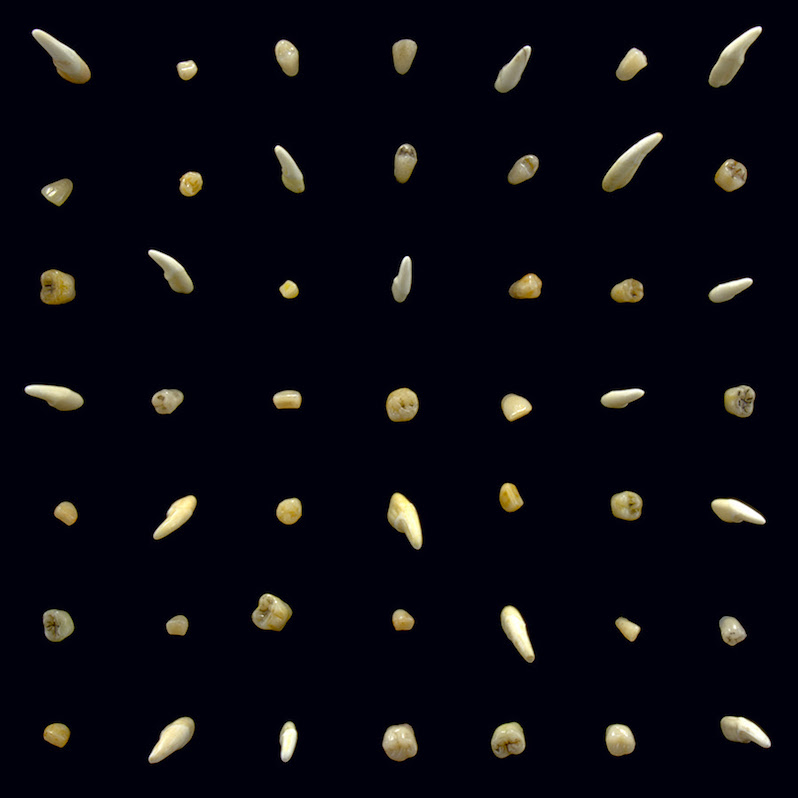

SPK – “Post-Mortem” (1982)

Bridging the sound-as-performance-art approach of pioneers like Einsturzende Neubauten with the medical-horrors shock aesthetic that Carcass would adopt later that same decade, Australia’s SPK—co-founded by composer Graeme Revell—employed a less overtly harsh approach to their industrial sound collage. Their 1982 album Leichenschrei, their most acclaimed work, pushes the boundaries of taste while innovating in sound, its original release foregoing the exercise of delineating separate tracks in favor of two uninterrupted sides of horror, mayhem and industrial funk. There are, however, tracks within those lengthy pieces, as indicated through later reissues, a highlight among them being this urgent dose of tense synth-punk pulse, overlain with bizarre and off-putting voice samples (“I remove the rectum itself,” “He tried to give me syphilis by wiping his cock on my sandwich”). Though it might introduce itself as abrasive, confrontational and disorienting, what resonates most with a track like “Post-Mortem” is just how musical nightmares can be. – Jeff Terich

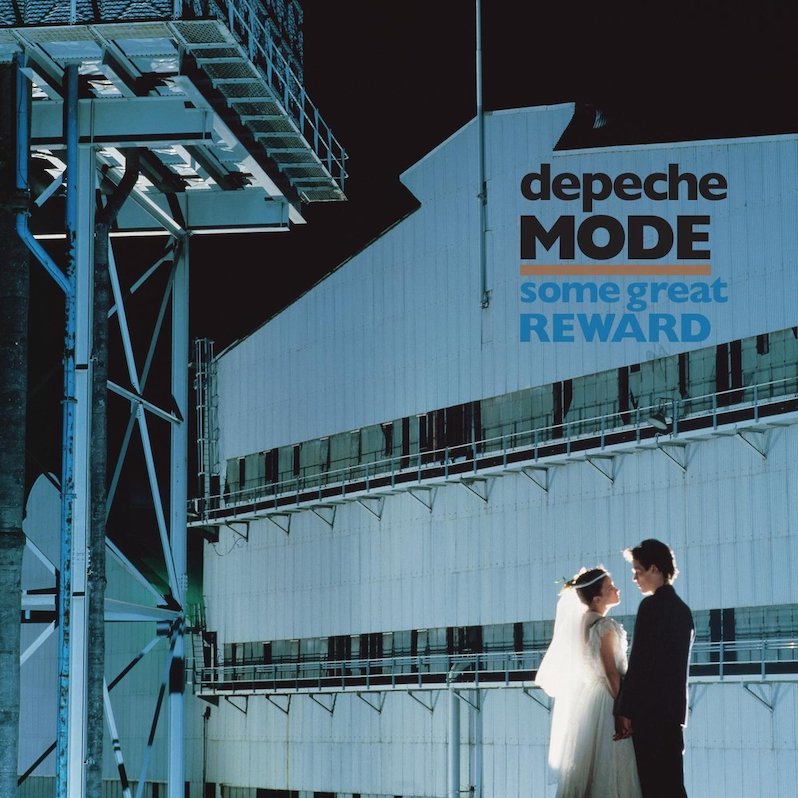

Depeche Mode – “People Are People” (1983)

The two chambers of industrial music’s heart, pumping its thematic blood, have long been personal relationships and sociopolitical awareness. Rarely has one song addressed both so succinctly, a timeless example of both protest pop and the genre’s minor-key pipe-banging. I mean, sure, band members have long associated the song with war and racism. It was recorded, released, and licensed for use in 1984 West Berlin, a year and location loaded with ominous overtones. But a lyric like “I’ve never even met you, so what could I have done” is an observation ready-made for the bullying, canceling nadirs of debates and campaigns currently playing out across social media. It took almost four decades to reach this point but at last, Depeche Mode, yes, we can understand. – Adam Blyweiss

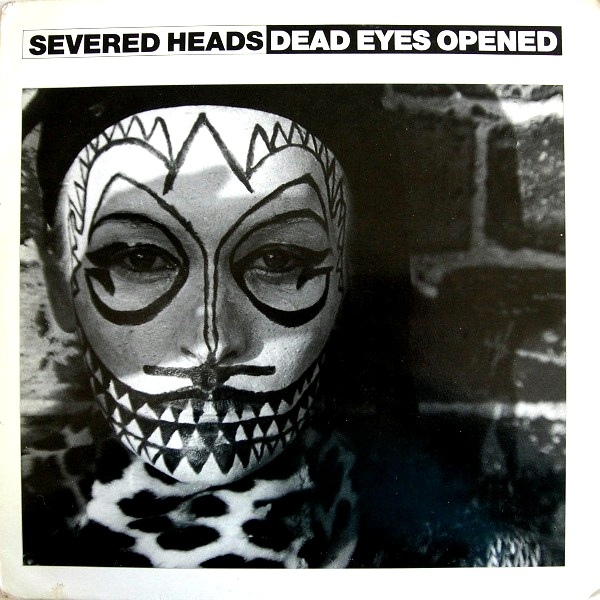

Severed Heads – “Dead Eyes Opened” (1984)

Here we see another of the varied colors of industrial. The coldness still remains, but here it is a coy connection to the body, the return of sensuousness like violence after waves of suicidality, the freshness of sensation in a space you might have imagined would have been absorbed by the dark of death. The rhythm is motorik and simple, a post-Kraftwerk lope like a ritual against sorrow. The humming of synth pads and longing melody, ripe with yearning, feels like the coming of tears burning at the edges of your eyes, pinched shut on the dance floor. You are here now; you made it; the waves of depression might roar back and take you tomorrow to that place you can’t come back from but you are here now. This is the sentiment that motivates all great coldwave and synth pop. You are here now. – Langdon Hickman

Einsturzende Neubauten – “Yü-Gung (Fütter Mein Ego)” (1985)

One of the lasting stereotypes of the industrial genre is People Banging on Metal. Many artists started out in that particular garage only to graduate to space-saving samples and synths. Few have remained as committed to handcrafted noisemaking as this Berlin collective, and Halber Mensch is where true musicality started to rise out of it. “Yü-Gung” is a 7-minute groove of growling percussion that would be damn near meditative were it not splashing in your eardrums or interrupted by blasts of scraping, rotating metal. And then there’s frontman Blixa Bargeld knitted throughout, barking out hyperbolic delusions of grandeur (“I am 6 meters tall and everything is important”) fueled by a cocktail of vodka and “Russian vitamins.” – Adam Blyweiss

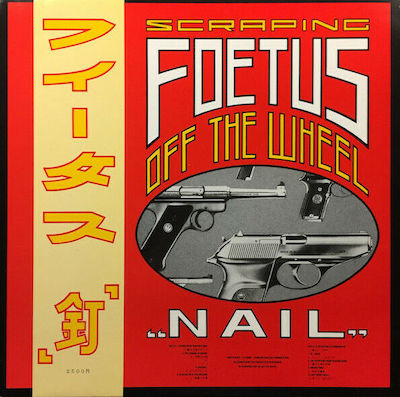

Foetus – “The Throne of Agony” (1985)

J.G. Thirlwell is among the most prolific artists on this list, having shown up on recordings by a significant chunk of these 45 artists, as well as a lengthy list of his own projects under different monikers (Clint Ruin, Steroid Maximus, etc.). Even his “main” project, Foetus, was presented in slightly different fashion each time it reappeared—You’ve Got Foetus on Your Breath, Scraping Foetus Off the Wheel—displaying a twisted sense of humor to go with industrial’s penchant for provocation. Yet even Thirlwell’s most cacophonous creations have showcased his tendency toward the cinematic, with tracks like Nail highlight “The Throne of Agony” pairing his signature mechanized, exclamation-point-addled production with a kind of exaggerated blues and early rock ‘n’ roll swagger found in David Lynch’s roadhouses and dive bars at the end of the world. Thirlwell croons, “Hello operator, get me no man’s land,” and from there he delivers the last Vegas revival after the apocalypse. – Jeff Terich

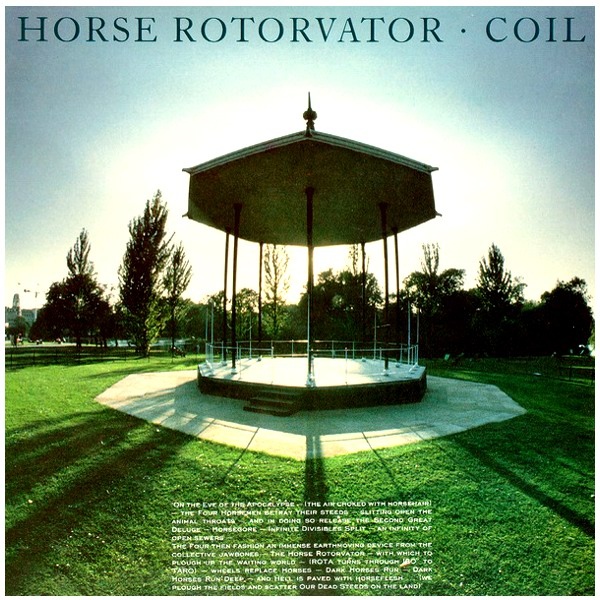

Coil – “The Anal Staircase” (1986)

It seems only appropriate that Coil—the project formed by Throbbing Gristle’s Peter “Sleazy” Christopherson, along with John Balance—after that group’s dissolution—bridge the gap between the freeform performance art provocation of early industrial music with its eventual crossover pop appeal. In fact, friend of the group Marc Almond of British hitmakers Soft Cell appeared on several of the group’s songs over the years. “The Anal Staircase,” the punishing march that opens the group’s 1986 masterpiece Horse Rotorvator, is the prototype for industrial rock as we know it, only without such overt hooks or heavy metal guitars. Employing a sample of Stravinsky’s “Rites of Spring,” the duo ushers in a dystopian dancefloor stomp that swirls sex, death, fear and intoxication into a terrifyingly thrilling revelation. Trent Reznor, industrial music’s biggest name, has often cited Coil among his greatest influences, and there are scant few moments on The Downward Spiral that don’t take root in some form here. – Jeff Terich

Big Black – “Bad Penny” (1987)

Chicago’s Big Black are probably best understood as a punk or post-hardcore band, but it’s less what they played than how they played it that made their sound more in line with their Wax Trax neighbors than might seem obvious on first glance. The group’s 1987 swan song Songs About Fucking is engineered to push the extremes, all extreme bass and high end, and Steve Albini using metal guitar picks to bring out an extra helping of harsh brightness in their menacing squeal. But it’s the use of their drum machine, Roland, that gave them the kind of robots-set-to-kill menace that makes a song like “Bad Penny” hit with the impact and intensity that it does. – Jeff Terich

Laibach – “Leben-Tod” (1987)

When this came out in 1987 Laibach stirred up the kind of controversy and infamy that got them banned in Yugoslavia for their satirical take on fascist iconography. Now they are regarded as cultural icons in their home country of Slovenia. Translating to “life and death” this song is one of the more serious moments on an album that also found them parodying Queen. All of the defining elements still found in industrial music can be heard here; when any one tells me they are a huge Rammstein fan, this is the song I play for them. Though droning and somewhat simple in retrospect, “Leben-Tod” has a firm thumbprint on music that followed its wake. – Wil Lewellyn

Nitzer Ebb – “Join in the Chant” (1987)

If you’re familiar with the typographic designs of the Dadaist and Italian Futurist movements of the early 20th century, you know the energy and meaning people can gather from what on the surface looks like utter nonsense. This beloved single from Nitzer Ebb’s breakthrough LP That Total Age is something like that, as Douglas McCarthy’s clipped chanting—“Gold! Church! Guns! Fire! Muscle and hate!”—rests on a precarious tipping point shared by anger and despair about, well, damn near anything. The Crusades, maybe? Consolidated wealth? War? Censorship? Laid against the group’s backdrop of gurgling bass synths and percussive heavy metal thunder, the British band’s fans have used many decades’ worth of combinations of these words to create just as many different anthems that speak to them. – Adam Blyweiss

Ramleh – “Product of Fear” (1987)

There’s not a lot of subtlety in power electronics, a genre defined by piercing frequencies and unrelenting hostility—a sound that Ramleh’s Gary Mundy never left behind entirely but eventually spiraled out from, taking on more of a psychedelic noise rock approach through later releases such as 2015’s Circular Time. But early on, Ramleh explored nuance and vulnerability through industrial’s most cacophonous and antisocial sector, his 1987 album Hole in the Heart balancing jarring static noise with a more affecting and minor key sound on standout track “Product of Fear.” A drone track that precedes the distorted hauntings of Tim Hecker by nearly two decades, “Product of Fear” is a moment of beauty amid a landscape of destruction, a curiously gentle noise track that finds warmth within chaos. – Jeff Terich

Tackhead – “Mind at the End of the Tether” (1988)

Hip-hop’s early use of hard rock and heavy metal samples offered a faint glimpse of what industrial metal might eventually sound like later on in the decade, but the first proper industrial and hip-hop fusion took place when engineer Gary Clail and producer Adrian Sherwood teamed up with the Sugar Hill house band. The resulting album, Tackhead Tape Time, is early electro and hip-hop turned sensory overload sound collage—dystopian Rick Rubin or The Bomb Squad with EBM basslines. “Mind at the End of the Tether,” the opening track on the group’s debut, is their vision perfected in seven minutes—darkwave synths, pulsing breakdance beats, disembodied voices of political figures and squealing guitar solos phasing in and out. The convergence of several underground sounds in one glorious collision. – Jeff Terich

The Beatnigs – “Television” (1988)

Bay Area musician Michael Franti may have set up permanent residence in jam-band nation with his reggae fusion, and earned rap street cred with Disposable Heroes of Hiphoprisy and early Spearhead releases. But before these, he was a screeching, half-singing mouthpiece for Beatnigs, working with Rono Tse and Kevin Carnes to shunt together harsh sampling, tinny drums, and basslines strung low enough to hit the floor. This opening track from their lone self-titled LP railed against the sociopolitical implications of the small screen and defined their genreless genre, a hybrid of rap and punk against backdrops that were equally eerie and angry. “Television” would be remixed by the likes of Adrian Sherwood and wholly redone by Franti and Tse in DHH, each version a testament to the original’s frantic, squirrelly energy and a reminder that it simply can’t be matched. – Adam Blyweiss

Front 242 – “Headhunter” (1988)

Industrial music has long embraced a distrust of authority and a fierce independence from subservience. Being a slave to another, to a state or system, to wages, and to technology (even as these musicians conspire with it) all comprise popular grist for this genre’s mill. Based on Jean-Luc de Meyer’s experience in the insurance industry, the lyrics of this centerpiece song of the Front by Front album conflate workforces and armed forces. Shuffling drums and stuttering, digitized classical and guitar strings support the Belgian band’s shifting moods from confident negotiations to echoing yells of desperation—”I’m looking for this man”—to garbled, fuzzy whispers on military radios. It takes something special to stand out from industrial’s storytelling pack. In blurring lines between new corporate hire, hired killer, and scientifically engineered killing machine, few tracks reach the heights of “Headhunter.” – Adam Blyweiss

Ministry – “Stigmata” (1988)

Pre-dating the aggressive and iconic debut of Nine Inch Nails (though just barely), Ministry’s impact on the industrial music and the wider landscape of heavy music overall is nearly immeasurable. From Al Jourgensen’s mic-in-throat, simulated choke-screaming (like he’s in the room with you!) to a vicious emulated blast beat via synths, “Stigmata” is a track that oozes aggression. Adding layers of heaviness and menace to Ministry’s earliest output, it’s become an iconic track not just for Ministry themselves, but a massive anthem for industrial as a whole. Snarling, well constructed, yet still imposing—an anthem for outliers. – Brian Roesler

Godflesh – “Like Rats” (1989)

Scalding, clattering, hateful. There are colors to industrial music, certainly, and vast wings of romantic and dance-oriented music and a million and one other approaches, but this is industrial at its most bestial and horrific. To socialist ears, “Like Rats” is the sound of the factory and the mine, the brutality against the working class both against the spirit and against the body. If Birmingham’s first great sons Black Sabbath were shaped by the gothic darkness of its industrial wastes, then Godflesh was born from the hopelessness of the dirt. There is no spirit here, no vessel for the beyond; only body, only physical pain, only torment. This is the first track on the first Godflesh album, the greatest work out of Birmingham, for a very simple reason: this is Godflesh. Even over 30 years later, it feels vicious and present-tense, a reality that is itself a compounding horror especially in the dying days of global warming. There really is no escape. – Langdon Hickman

My Life With the Thrill Kill Kult – “The Devil Does Drugs” (1989)

A couple years ago I met up with Frank Nardiello, aka My Life With the Thrill Kill Kult vocalist Groovie Mann, for an interview and told him their debut album I See Good Spirits, I See Bad Spirits album was the soundtrack to one of the most depraved times of my life. He thanked me and said, “That is one of the best compliments I’ve gotten.” The Thrill Kill Kult have built a reputation as being purveyors of sex-crazed discotronica, but their earlier material painted a much darker picture. In the late ’80s, the sonic landscape of industrial was much different, with samples being an integral part to the songs, sharing the spotlight almost as much as the vocals. The repetitive drone of a track like “The Devil Does Drugs” hypnotizes and lures you into a lurid, horror-movie-like environment. – Wil Lewellyn

Nine Inch Nails – “Head Like a Hole” (1989)

“Head Like a Hole” is an abrasive industrial-rock song many industrial fans wouldn’t call that abrasive. For most everyone else, the ferocious guitars and shout-sung chorus on Nine Inch Nails’ breakout single had sledgehammer force that its indelible pop hooks didn’t dull. Indeed, if Trent Reznor had the recording and production resources he’d later enjoy, it likely would’ve hit harder; the remaster of Pretty Hate Machine somewhat bears this out.

“Hole” is lyrically direct to the point of simplicity, and that’s why it works. It’s an ideal contrast with the complex arrangement and instrumentation. More than a few of the rock and new wave fans drawn in by the song’s melodies and riffs added more industrial to their palates as a result of hearing it. Whatever chagrin that brings to purists, it means “Hole” and Machine are fundamental to the progression of the genre. – Liam Green

The Young Gods – “Rue des Tempêtes” (1989)

Switzerland’s Young Gods followed a similar sonic path as Killing Joke, their brand of industrial leaning heavier on rock. In 1989 they were still ahead of their time, though perhaps not as experimental as where they would eventually wander off to on albums like the electronics heavy Only Heaven. Yet tracks like “Rue des Tempêtes” are a clear reminder that they’re a band whose name needs to be brought up more in discussions of industrial music. Always setting themselves apart with their use of organic drumming rather than relying solely on programmed drums, as heard here, Young Gods proved more than capable of drawing out the genre’s more noise-tinged punk roots. – Wil Lewellyn

Meat Beat Manifesto – “Helter Skelter” (1990)

This lead single from the English electronic band’s 99% album was powered by syncopated drum loops and unresolved synth squiggles, revisiting the jazz influences of their debut Storm the Studio. But it also lived up to the rep built up by Meat Beat’s presence on the influential industrial label Wax Trax!, an unexpected business reality largely out of their control. Producer Jack Dangers and his friends loaded the track with samples of both industrial contemporaries (23 Skidoo, Revolting Cocks) and musicians powered by similar hardware (reggae toaster U-Roy, novelty rap act Air Force 1), plus a legendary Malcolm McDowell scream and other clips from the cult-classic film adaptation of A Clockwork Orange. A megamix in camouflage, give it just one spin and it’s in your brain, dissonant and dystopian. – Adam Blyweiss

Pigface – “Suck” (1990)

The original 1990 iteration of “Suck” is a maelstrom of drumbeats performed by Pigface co-founders Martin Atkins and Bill Rieflin, Paul Barker’s bass and the intermittent sound of a projector, underneath nihilistic lyrics sung by Trent Reznor. It’s an interesting track, somewhat in line with the Einstürzende Neubauten corner of the industrial universe.

Liner notes on the album Gub credit “Suck” to those four men. On Nine Inch Nails’ Broken EP, “Suck” is credited to “T. Reznor/Pigface.” This frustrated Atkins, who played drums on that version and throughout Broken. That said, Reznor’s arrangement is completely different (he claimed he didn’t like the original). Pigface’s live versions mostly follow the NIN blueprint. In terms of who took what, I’d call it a draw. But comparing the versions affords you the opportunity to examine industrial through differing prisms. – Liam Green

Skinny Puppy – “Tormentor” (1990)

After Rabies, an album featuring Ministry’s Al Jourgensen—who made Skinny Puppy sound an awful lot like his band—the Vancouver industrial trio returned to their horror-industrial fundamentals with Too Dark Park. “Tormentor,” the lead single, is considerably more tame compared to much of the album, with Nivek Ogre’s vocals less upfront and confrontational in the mix and synth lines that slowly creep rather than directly attacking your ears. But rest assured you are not in safe territory here. Ogre’s lyrical abstractions suggest physical disease and mental decay just around the corner, bolstered by the ominous proclamations of sampled film characters. “Tormentor” is a good way to test the waters of this band before you delve further into Park or other Skinny Puppy classics like VIVIsectVI. – Liam Green

Curve – “Faît Accompli” (Extended Extended Extended) (1992)

The London duo of Toni Halliday and Dean Garcia reached critical mass way too soon in their career as Curve, on a series of EPs and debut LP across the early 1990s. They were too shoegaze to be baggy and vice versa, but used the distortion of the former and the techno elements of the latter to create tortured goth-pop. Whether in original or extended form, this monster single from Doppelganger has no choice but to track as industrial. It’s crammed with flanged bass atmospheres, blasts of air that double as drumbeats and synth fills, and a signature guitar drone in the chorus that suggests both a drill and a fuzzed-out backup singer. Turning lyrics about the depressive inevitability of fate into a come-hither grind, “Fait Accompli” shares DNA with work from the likes of KMFDM and My Life with the Thrill Kill Kult before passing it on to Republica and Garbage. – Adam Blyweiss

Front Line Assembly – “The Blade” (1992)

In a career spanning five decades and extending into almost 20 meaningful side projects and collaborations, it was FLA’s sixth proper album Tactical Neural Implant where they produced electronic-based industrial that defined not just their career but the genre as well. “The Blade” is more a sonic anthem than a thematic one—its lyrics suggesting BDSM and its samples of Black responses to racist violence make for a juxtaposition that gets more puzzling with age. But its synths and vocodered singing, combined with instrumentation pulled from James Brown, Slayer, and Paris (who appears on this list once more!), create electronic body music that gurgles like an underground river, its rapids in the dark sending listeners on a dangerous and exciting ride. – Adam Blyweiss

Consolidated – “Guerrillas in the Mist” [ft. Paris] (1992)

The rise of hip-hop was truly more “industrial” than most cognoscenti care to admit. Scratching turned records and record players into catch-as-catch-can instruments. The lifting of samples gave music and other audio new, shifted contexts. And the skillful pastiche by artists from Grandmaster Flash to DJ Shadow created parties, scenes, and stories where none previously existed. A foundational industrial act that successfully imprinted their own rap on the technologies shared by both styles is Consolidated, and they featured fellow San Franciscan Paris on this indictment of racism in the justice system, one so vengeful as to demand an eye for an eye multiple times over. They may not have been household names, but their rhymes over staticky funk and tolling bells definitely gave Public Enemy and Ice Cube a run for their money. – Adam Blyweiss

KMFDM – “A Drug Against War” (1993)

The standout single from KMFDM’s seventh album Angst, “A Drug Against War” was the kind of anthem the pioneering German industrial band needed. Their fanbase not only embraced it but it proved to be one of their most defining moments, later appearing on Beavis and Butthead, thus opening the band to a more mainstream audience who after being exposed to the likes of Ministry and Nine Inch Nails was already primed for the band’s attack of thrash fueled guitars with a driving militant beat. It became a rallying cry to the dance floor at goth-industrial nights everywhere. – Wil Lewellyn

Björk – “Army of Me” (1995)

One of Björk’s most enduringly popular songs, the bombastic intro to Post, was an antidote to the delicate playfulness of her Debut, all swirling darkness and smooth venom. She cranks up John Bonham’s iconic drumbeat so far that the already aggressive snare hits like a gunshot, and the wriggling bass line alternates with a groaning siren, announcing the chorus like a klaxon. That shift is mirrored in Björk’s husky vocal attack, getting both louder and lower, contrasting with the sickly sweet verses. The dark edge to this song is just one of the many costumes Björk slips in and out of, but the legacy of “Army of Me” transcends her discography, marking a breakthrough of industrial pop. – Forrest James

Velvet Acid Christ – “Fun With Drugs” (1999)

This track from Velvet Acid Christ’s 1999 album Fun With Knives is a culmination of their work during the ’90s on Metropolis Records, and their transition into a more EDM-driven direction as they changed with the times. Narrated by samples from the film adaptation of Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas, the track captures that tale of depravity and takes it to a darker more dystopian place. More of a bad trip than any kind of light and love hippy fest, they retain the kind of aggression that became their trademark over the years. – Wil Lewellyn

Portishead – “Machine Gun” (2008)

Once synonymous with trip-hop, a sound the group helped put on the map through their landmark 1994 debut Dummy, Portishead’s return after a long break with their 2008 album Third found them embracing jet-black moods and sandpaper textures. The album’s lead single “Machine Gun” is named for the abrasive throb of its drum sample pattern, its sound taken from an old organ and made punchier and dirtier in its aggressive repetitions, while the song’s eerie synth melody is inspired by the cinematic and sonic horror of John Carpenter. Though the band’s stated influences at the time were rooted more in vintage psych such as Hawkwind and Silver Apples, on “Machine Gun” the end result is something more like Neubauten noir, an intoxicating headphone experience with the subtlety of—well, it’s right there in the name. – Jeff Terich

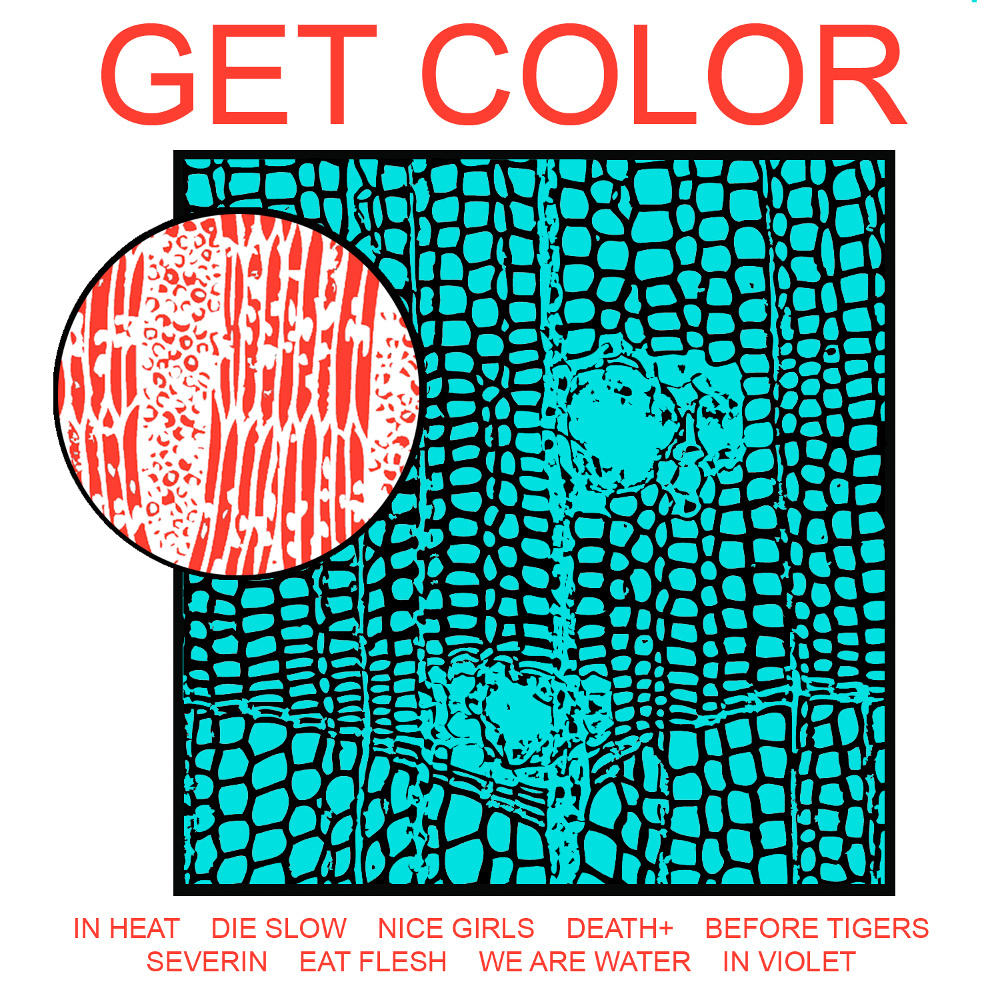

HEALTH – “Die Slow” (2009)

HEALTH emerged in the late 2000s, a time when industrial was not itself a dominant genre but more than a few bands who flirted with it—including A Place to Bury Strangers and Deerhunter—were receiving plenty of critical notice. “DIE SLOW” establishes a template that HEALTH has often since followed: corrosive riffs and synths grounded in a relentless backbeat, with Jake Duzsik’s ethereal yet sinister clean vocals floating above it all. The impressionistic lyrics detail a probable suicide with clinical cruelty, but in the great industrial tradition, HEALTH somehow makes something so vicious sound so irresistible. – Liam Green

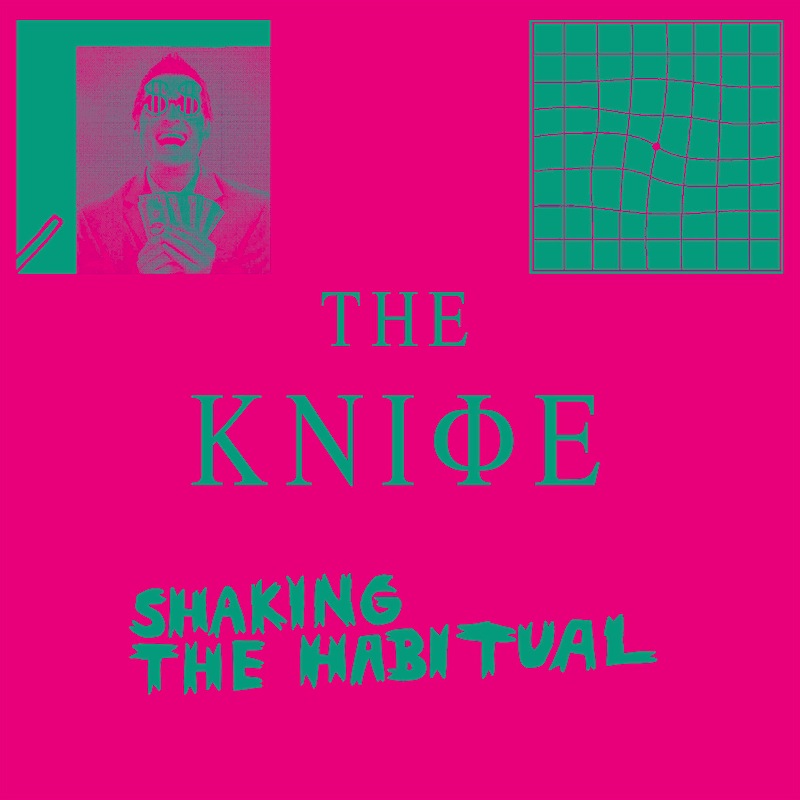

The Knife – “Full of Fire” (2013)

“Full of Fire” swept the world in 2013 on the heels of the news that the album it emerges from, Shaking the Habitual, would be The Knife’s last. It’s a manic dance, bodies streak with paint, as the building burns down. The production feels in turns like peak ’80s Janet Jackson industrialized dance-pop, foregrounding the martial aesthetic that can emerge in that space, pressed against the melting head psychedelia of underground dance music. The Knife use industrial music here as the fusing point, a new kind of matter produced by the conflict of the approachable against the arthouse, neoclassical motifs fused into body music. It reeks of an opium den, Baudelaire and Rimbaud spilling from the lips as sweat drips from your body, lasers piercing the aimless smoke from cigarettes and blunts. This is industrial music as psychedelic experience, reaching the mind beyond the mind. – Langdon Hickman

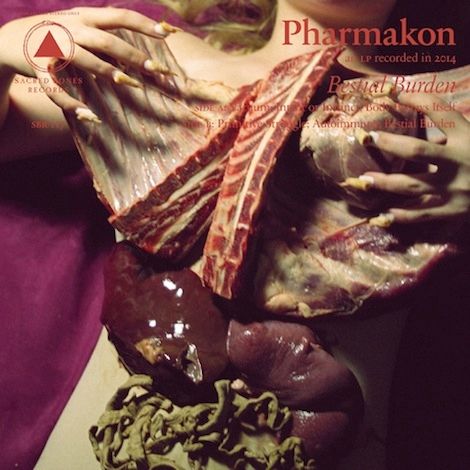

Pharmakon – “Body Betrays Itself” (2014)

Pharmakon borrows the alphabetic album naming gimmick from another great group, Morbid Angel, appealing to the visceral darkness of the human body in disease and dysmorphia and decay where Morbid would draw from the spiritual darkness of the world. If Godflesh is the sound of the industrial clatter of the machine, then “Body Betrays Itself” is the sound of hospital equipment, of terminal disease, the way blank empty space stretches out in the coffin-like confines of the hospital room. For those of us who’ve either been deathly ill or who have had loved ones in those positions, its harrowing stuff; the interior scream that can’t emerge when staring at a dead family member cold in the hospital bed. This is a hammer. – Langdon Hickman

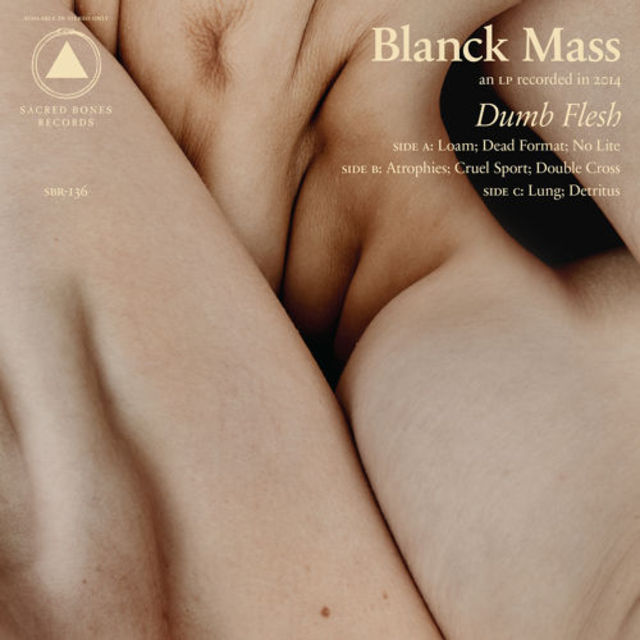

Blanck Mass – “Detritus” (2015)

The last track on Blanck Mass’ second album Dumb Flesh opens with a hissing mess of static, distinguished only by a growling bass buried somewhere underneath. The sound seems interminable, proceeding uninterrupted for nearly three minutes. It’s fucking difficult to listen to at all. So it definitely isn’t easy to notice the melodic synths building quietly in the background. But the static begins to fade out as the melody comes up, and once an equilibrium is reached everything stops, a pumping bass comes in, and the song blossoms into an anthemic feat of wonderment. There are many genres and descriptors that can be ascribed to Blanck Mass’ sound here, and perhaps the simple fact that none of them fully encapsulate it is what makes “industrial” one of the most apt. – Forrest James

Youth Code – “The Dust of Fallen Rome” (2016)

Los Angeles duo Youth Code the tried and true old school influences like Ministry and Skinny Puppy and gave them a fresh update on albums like 2016’s Commitment to Complications. This song marks the high water mark of songwriting for the project, with an anthemic chant of a chorus that would have stood proud among their industrial heroes in the ’90s . While much of the younger blood that tries to bring back the classic era of industrial music tends to focus on recapturing a sound, Youth Code proved they could add to that foundation with a great batch of new songs. – Wil Lewellyn

Author & Punisher – “Nazarene” (2018)

One-man industrial-machine band Tristan Shone is a trailblazer in the present industrial metal revival. He is not content just downloading patches of sound to recreate industrial music of the past, but he built his own drone machines to make them with—which are even more imposing in person. While this alone would be novel enough, the San Diego artist takes it a step further and employs those punishing sounds in the service of creating compelling songs. “Nazarene,” a standout from 2018’s Beastland, finds him reflecting on religion in a post-apocalyptic landscape (“We built a cross, all hope was lost”), with hooks as massive as the crushing beat beneath them. – Wil Lewellyn

Lingua Ignota – “DO YOU DOUBT ME TRAITOR” (2019)

Lingua Ignota is consistently one of the most dynamic and powerful artists in underground and experimental music, her contributions to industrial’s continuum acting like a mirror to its future. While many of Kristin Hayter’s tracks are visceral and harsh, far from pleasant affairs, “Do You Doubt Me Traitor” in particular growls and screams, yearns and hollows out the listener by building a menacing array of pianos colliding with scratching spaces. It’s industrial without its rhythm, purposefully uncomfortable. But that’s a meager description to describe the full experience, something that counts on the listener how it builds on and transforms that which came before it. Its place in the canon of dark, heavy music can’t be doubted, merely explored and experienced. – Brian Roesler

clipping. – “Say the Name” (2020)

L.A.-based group clipping. have incorporated sounds from industrial and noise music since their earliest releases. They pivoted hard into horrorcore with the 2019-20 diptych of There Existed an Addiction to Blood and Visions of Bodies Being Burned, while retaining their abrasive production style.

“Say the Name,” Bodies’ first single, immediately proclaims its heritage with an interpolation of Scarface’s signature opening lines from Geto Boys’ “Mind Playing Tricks On Me.” But Daveed Diggs’ steadily rapped lyrics are as much an evocation of all-too-real life—police violence, addiction, poverty, classism and racism—as they are about demon babies and slasher-movie slayings. The song is not shy about its influences, including Candyman and “Closer” by Nine Inch Nails alongside the aforementioned Geto Boys. But the stew Diggs and producers William Hutson and Jonathan Snipes create from them is a nightmarish original. – Liam Green

Backxwash – “Nine Hells” (2021)

Creaking synth percussion introduces Backxwash on the penultimate track of her latest album, I Lie Here Buried With My Rings and My Dresses, rapping about a spiraling drug bender, a disorienting echo on her vocals. Subtly nestled in the mix, Ada Rook’s sinister guitar hook builds both suspense and a sense of determination. Huge pulsing synths blare out at the end of the song, as much dance bass booming as alarm bells ringing, while Backxwash screams her way through the pain to some kind of relief. The track strikes a masterful balance between the personal and performative, equal parts debaucherous and horrific. It’s a bleak rock bottom that grinds the darkest themes of the project into our minds before the finale brings resolution. – Forrest James

Support our Site—Subscribe to Our Patreon: Become one of our monthly patrons and help support an independent media resource while gaining access to exclusive content, shirts, playlists, mixtapes and more.

No Die Krupps but NIN are included? Difficult to imagine Pretty Hate Machine without the early DK stuff ?

Otherwise, yeah nice summary. And yes some bands aren’t particularly human friendly, but when looking at history they should be included.

Eww.. why is Nine inch nails and kmfdm on this list? What about Noise Unit and White house? Where’s Brighter Death Now and Mental Destruction? It’s a alright list but there’s other better bands that are from the same time that never get mentioned. It’s usually always the same bands.

I am thankful to the author for at least being honest about omitting some history to conform to contemporary taboos, but I think sanitizing the past doesn’t teach anyone anything and avoiding controversy or difficulty to satisfy norms runs counter to the spirit of much of what is called industrial.

it’s not sanitizing the past so much as not wanting to give editorial space to either rapists or people with far-right politics.

SPK?

they’re on the list

thank you for the broad overlook. it is like a skipping stone across many of my own musical adventure. and mentions of bands missed. will explore them.

there will always be debate about influences and thresholds.

but Portion Control from UK 80s is worthy mention in the footnotes of most industrial bands term paper knowingly or subliminally.

thanks for the article

There is a Paris song attributed to Consolidated, “Guerillas in the mist “

it’s Consolidated with Paris